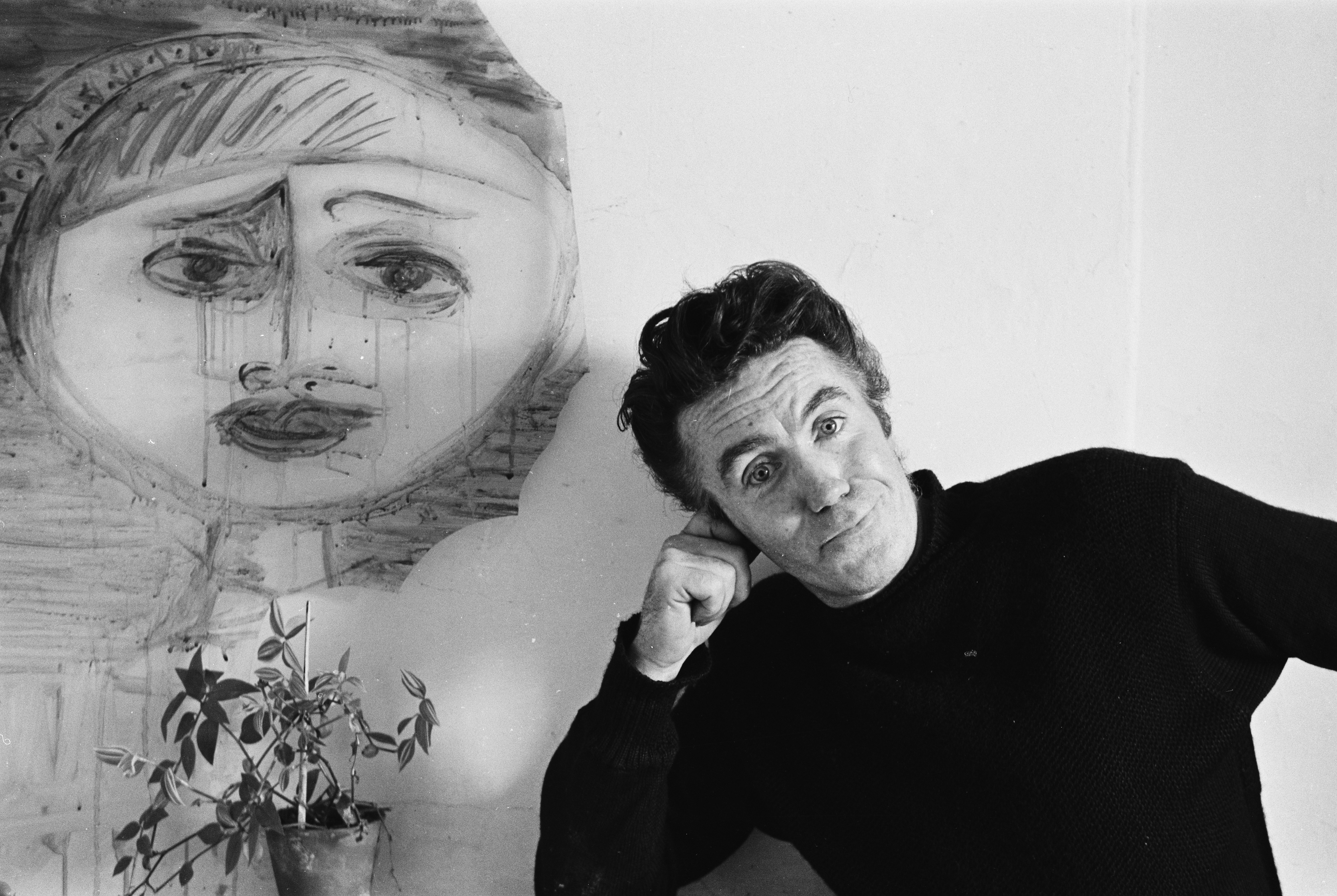

W. S. Graham, the Old Coastguard Cottage, Gurnard’ s Head (ca. 1958). Photograph copyright the Estate of Michael Seward Snow, 2018. All rights reserved.

When W. S. Graham died in 1986, he died in neglect. And yet in 2018, his centenary year, Graham’ s reputation seems assured. Over the three decades since his death, it has been a commonplace to lament, and express incredulity, that his work had never reached a larger audience, that he had remained a “poet’ s poet. ” Read any obituary from 1986, or any of the reviews that greeted the posthumous publications of Uncollected Poems (1990), Aimed at Nobody : Poems from Notebooks (1993), and his New Collected Poems (2004), and you’ ll find the same refrain: underread, undervalued, understudied. But in Britain, he is increasingly recognized as one of the major lyric poets of the twentieth century, and a series of publications and exhibitions have meant that he is being read like never before. 2018 has also seen an increased reception of Graham in the US: a special feature on “W. S. Graham at 100 ” in Poetry appeared in January, and an NYRB Classics volume of Graham’ s Selected Poems, edited by Michael Hofmann, was published in November. This Chicago Review special issue seeks to kick-start Graham’ s posthumous critical reception in the US.

Ironically, in his lifetime Graham enjoyed a more concerted critical reception in the US than at home. Still in his twenties, he was awarded a Rockefeller Grant in 1947–48, lecturing at NYU (his inaugural address there, “Forces in Contemporary Poetry, ” unfortunately does not survive), and published poems in the Hudson Review and the Sewanee Review (the latter accompanied by an article by Vivienne Koch, the first dedicated to his work). His only published critical statement on poetics, “Notes on a Poetry of Release, ” was published by both Poetry Scotland and the Quarterly Review of Literature (UNC Chapel Hill) in 1946. He returned to the US in 1951–52, where he met Ezra Pound and stayed for a while with the experimental filmmaker Len Lye—one of many times where he found himself in close contact with modernist artists across different media. Even as Graham’ s work fell into neglect in Britain in the 1950s and 60s, he continued to find readers across the Atlantic. In a letter dated 14 October 1969 he wrote, “POETRY CHICAGO seem very much for me ” (NF, 234), and indeed, Poetry published four of Graham’ s most significant poems from this transformative period in his writing life: THE CONSTRUCTED SPACE (1958), MALCOLM MOONEY’ S LAND (1966), THE BEAST IN THE SPACE (1967), and CLUSTERS TRAVELLING OUT (1968). By contrast, he published only two poems in British magazines during this period. The second serious critical engagement with his work came in the American poet-critic Calvin Bedient’ s Eight Contemporary Poets (1974), which described him as “the most piquantly original poet now writing in English. ” It would be several years yet before British critics started producing such responses to Graham’ s oeuvre.

Yet, while Graham’ s reputation has burgeoned in the UK since his death, it has declined on the other side of the Atlantic. Why is this? In the UK, the trends and fault lines of the poetry scene have realigned in such a way as to endow Graham with far greater retrospective significance, with young poets in particular increasingly receptive not just to Graham’ s thematic concerns, but his creative processes and the formal operations of his verse. The publication earlier this year of The Caught Habits of Language (ed. Rachael Boast, Andy Ching, and Nathan Hamilton, 2018), a centenary volume bringing together previously unpublished work of Graham’ s with poems written for Graham—both by poets contemporary to Graham such as Hugh MacDiarmid and George Mackay Brown, and by poets contemporary to us—demonstrates that admiration for Graham today cuts across the historic divisions that have characterized British poetry. The anthology contains prominent figures in the British avant-garde, familiar to Chicago Review readers: Tim Atkins, Andrea Brady, Vahni Capildeo, Emily Critchley, Peter Manson, as well as Denise Riley and John Wilkinson, both of whom feature in this special issue. And yet alongside them are poets more readily associated with the “mainstream ”: John Burnside, Sasha Dugdale, Ian Duhig, Jen Hadfield, Sarah Howe, Jackie Kay, Roddy Lumsden. In British poetics today, Graham is perhaps a uniquely unifying figure.

But this is a recent phenomenon. Graham was peculiarly ill-served by the mainstream/avant-garde schism that can be traced back at least to the 1950s backlash against modernism, which crystallized around “The Movement, ” and the development of a neo-modernist “British Poetry Revival ” as a reaction to this in the 1960s. Graham’ s collection The Nightfishing (1955) appeared in the same year as The Movement’ s first attempt at hegemony building : Poets of the 1950s (Graham was not one of them), and he received damningly faint praise from critics who were patrolling the borders of this new orthodoxy. Donald Davie complained of the “unvarying solemnity of the tone ” and Graham’ s desire to create an “artefact, not a communique, ” while Peter Russell’ s dismissal of Graham’ s verse as “syntactically quite unnecessarily eccentric ” was prefaced by that classic strategy of commonsense conformism: “Either I am very obtuse, or… ” Most unfortunate was Roy Fuller’ s characterization of “the precise manner of Mr W. S. Graham ” as “stammerings, pretentious word order, enjambments emphasizing themselves by unemphasis, and that solemn, inarticulate conception of the poetic ego. ” Like Davie, he saw the chief failing of Graham’ s poetics as “a constant failure of the power to communicate. ” Graham’ s poetry was, first and foremost, an affront against utilitarian information-transfer.

Similarly, although late-modernist poets were more alive to Graham’ s significance, he remained an outlier. As Wilkinson has suggested, British avant practice from the mid-1960s onwards can be understood as “A Black Mountain/Buffalo out-growth, a product of the Olsonian force-field. ” Indeed, one of the major motors for the British Poetry Revival was the time Ed Dorn spent at the University of Essex, where his impact was particularly felt by Tom Raworth and J. H. Prynne. Graham’ s reemergence as a major figure has coincided with a more heterodox poetic culture in the UK: as the major gatekeepers of literary taste, from established presses to newspaper reviewers, lose their dominance (not least as new technologies allow poets and readers to bypass them), so new constellations of styles, techniques, and thematic concerns start to coalesce, and so new histories can start to be told.

Wilkinson’ s description of the British avant-garde might also indicate why Graham should have fallen into oblivion in North America: while Graham is easily legible within a modernism organized around Pound, T. S. Eliot, Gertrude Stein, or Wallace Stevens, his commitment to “the whole / Formal scheme which Art is ” (NCP, 182), and his stated desire to “make / An object that will stand and will not move ” (NCP, 164), seem the very opposite of the open-field poetics which, from Black Mountain and Buffalo, but also San Francisco and Vancouver, would so shape North American poetics over the last half century. If Graham, like Stein, Frank O’ Hara, Barbara Guest, and so many others, was “a poet among painters, ” then the painters he was close to remained for the most part committed to a post-Cubist medium specificity, whether figurative or abstract. It was precisely this kind of work that the poets and artists coming out of Black Mountain were pushing against.

Interestingly, one can also read this as a history of trends in the visual and plastic arts: just as Graham’ s own reputation among poets has increased, so has there been an increased interest in the work of many of the artists he was close to—from the neo-Romantic painters, such as John Minton and “the two Roberts, ” Colquhoun and MacBryde, who were his closest friends in London in the mid-1940s, to the primarily constructivist painters in and around St Ives who were his most longstanding artistic community, from Wilhelmina Barns-Graham to Peter Lanyon, from Bryan Wynter to Alan Lowndes, from Roger Hilton to Sandra Blow. David Lewis’ s reminiscence of Graham, included here, not only situates Graham within the social life of this artistic community, but also demonstrates how he was trying to think through the dynamics of pictorial abstraction for his own poetic practice, notably in the disarming question: “When I look at an abstract painting, what is the painting I am looking at abstracted from? ” However, it is most pronounced in poetics. As Eric Powell argues in his contribution to the essay cluster published here, Graham’ s poetics seems on the face of it illegible to the overarching concerns and practices of advanced US poetic practice since the early 1960s. Sam Buchan-Watts notes that Graham is distinctive, even among poets of his generation, for his continual exploration of “nostalgic ” verse forms such as the ballad, something Buchan-Watts links to Graham’ s commitment to what he called “the formal construction of time made abstract in the mind’ s ear ” (NF, 162).

The sketches, drafts, letterpoems, as well as abstracts, landscapes, and decorated letters that are collected in this volume—some abandoned, some of which became the basis of published works—give an insight into how Graham built up the elements of his poems into finely tuned art objects. But they also give a glimpse of a different kind of creativity than the one visible in the work Graham published during his lifetime: a creativity that inheres in the provisional, the occasional, the improvisatory, where the objects produced, far from standing and not moving, are unstable, constitutively in flux. In this sense, these materials complement Graham’ s other works in the public domain, from the letters to the posthumously published poems and sketches, and offer us a fuller appreciation of his poetic achievement. But they also show closer affinity between Graham’ s way of writing and US experimental praxis than one might initially have thought.

Prolific in his twenties—he published four collections between the ages of twenty-three and thirty, in 1942, 1944, 1945 and 1949—Graham became increasingly painstaking as he grew older. The Nightfishing was composed over eight years, and when Malcolm Mooney’ s Land was published in 1970, only ten poems had appeared in print in the preceding fifteen years. Yet archival materials accumulated by Graham’ s friends from the mid-1950s onward point to nonstop creative activity throughout this time. In her foreword to Aimed at Nobody, Graham’ s widow, Nessie Dunsmuir (a fine poet in her own right), wrote:

time and again he said that he did not disown any of his poems. When commenting on his work, he remarked that every poem was relevant; that it was integrated into the whole body of his writing. Were it later to have been a question of choosing a book of Complete Poems, I know he would have included everything that he wrote and kept.

That he wrote and kept. Yet, strictly speaking, Graham himself kept very little. In a biographical sketch in The Nightfisherman, Michael and Margaret Snow write that when Graham and Dunsmuir moved house in 1962, they did so by “abandoning everything not immediately needed and walking out leaving the door open and clothes, books, papers behind ” (NF, 187). What Graham did do, however, was gift manuscripts and drawings to friends: from the mid-1950s, friends including Julian Abercrombie (née Orde), Alan Clodd, and Biddy Crozier were serving as informal patrons, remunerating Graham for these gifts; later, Ronnie Duncan, Tony Astbury, and Ruth Hilton provided further support. Many of these materials have now made their way to various archives: Clodd’ s, Crozier’ s, Duncan’ s, and Hilton’ s are all now in the National Library of Scotland, which in recent years has built up a rich collection of Graham’ s writings. But one friend-patron stands out: the poet and literary critic Robin Skelton. A friend of Graham’ s from the late 1950s, in 1963 Skelton moved to Victoria, British Columbia, to take up an academic post at the university there. Shortly after his arrival, Skelton was tasked with setting up an archive of British literature, and as a result was able to offer Graham a stipend in exchange for drafts, manuscripts, and other materials. This became a formal arrangement in 1972, and Graham started to post drafts of ongoing poems, as well as other materials dating back well over a decade, from Madron, in the far west of England, to Vancouver Island, in the far west of Canada. These include large numbers of draft stanzas for the long poem IMPLEMENTS IN THEIR PLACES (1969–72) and other major poems in Graham’ s oeuvre: TEN SHOTS OF MISTER SIMPSON (1971), CLUSTERS TRAVELLING OUT (1968), and THE FOUND PICTURE (1974–76). But they also include many verse works that, for whatever reason, Graham did not publish and did not pursue further, and an artist’ s book, as well as paintings and sketchbooks. Graham was not simply a poet among painters, but produced a distinctive visual oeuvre of his own. The majority of the works published in the current issue date from this period, and come from this archive.

These works hold a curious position in Graham’ s oeuvre. Following Dunsmuir’ s remark, they were not “disowned ”: if Graham “would have included everything that he wrote and kept ” in a Complete Poems, then the fact that he sent these works to Skelton (and, in three cases, to Clodd), where he knew they would be preserved and archived, suggests that he intended them for posterity. And yet, he chose not to publish them during his lifetime, whether individually or as part of collections. Borrowing from Graham’ s own terminology, we might name these different texts “approaches. ” Some read as preliminaries to later works: ON THE DEATH is in a notebook largely given over to preparatory sketches of his elegy to Peter Lanyon, THE THERMAL STAIR; TO BRYAN WYNTER DEAD similarly precedes and anticipates his celebrated elegy, DEAR BRYAN WYNTER. In her contribution, Lavinia Singer situates both preliminary poems within Graham’ s broader engagement with visual arts. Denise Riley’ s poem “And as I sit I feel the gaze ” responds to another unpublished work of Graham’ s collected in this special issue, the brief depiction of MR LE GRICE’ S PORTRAIT CLASS. Other approaches read as general explorations of images, sensations, or phrasings around the same topic—some of which will be taken up elsewhere, some left to contingency. For instance, Jeremy Noel-Tod offers an account of the drafting process which led to TEN SHOTS OF MISTER SIMPSON, in particular noting how the poem began as an overt account of the predicament of a Holocaust survivor, before Graham abstracted away into more allusive reflection on language, communication, and the construction of images (photographic in the poem, but by analogy the poem’ s own mode of imaging). In Aimed at Nobody, Blackwood and Skelton included “further shots ” of Mister Simpson; here we publish [DRAFT SHOTS OF MISTER SIMPSON] hitherto not included, to provide a more extensive account of the way this key poem was composed.

One place where the relation between draft and “finished ” work is most fraught is in Graham’ s various approaches to Greenock, his childhood home, discussed by Hannah Brooks-Motl. This shipbuilding town, twenty miles west of Glasgow, on the banks of the river Clyde, had long exerted a pull over his poetic imagination. Yet he remained dissatisfied with what he had produced. Writing to the poet and translator Michael Hamburger in 1966, he lamented: “I have always wanted to speak about Greenock, my home town and that time, but I have felt I wasn’ t able to make it into ‘poetry’. I mean the correct distortion. Or maybe I mean old Steven’ s [sic] It Must Be Abstract. ” In the coming years, Graham would produce several poems about Greenock, and indeed, memories of Greenock are interwoven throughout Implements in Their Places (1977); in particular a passage of WHAT IS THE LANGUAGE USING US FOR? (1974) is organized around an imagined memory in his home town, as is his address to his late father, TO ALEXANDER GRAHAM (1974). LOCH THOM (1976) and GREENOCK AT NIGHT I FIND YOU (first published in 1977) also play in the indeterminate space between memory and dream, staging a return to his hometown and its surrounding landscape. Yet these hardly cover the full extent of Graham’ s attempts to make Greenock into “poetry. ” The approaches Brooks-Motl discusses are from the beginning of this ten-year period. As well as constituting the first “approaches ” to one of the major themes of his later work, Brooks-Motl identifies in these writings a conceptualization of nostalgia that accords with their status as “draftworks ”: sociable, generative, marked by slippages and provisionality. The lack of finition becomes part of their modes of thinking and communicating.

Graham’ s archive indicates not only his compositional practices, but an everyday sociality that both shaped, and was shaped by, such practices. Today Graham is best known for his epistolary poems, and also for his letter writing (his selected letters were collected in 1999 in The Nightfisherman). Among the pieces we publish here are just a small number of the many occasional poems and letter poems he wrote for friends, either as personal gifts or on the spur of the moment. Buchan-Watts looks at how his ballad THE SONG OF THE TOWER, given to Sven Berlin in 1949, shows him working with a form that in the mid-1950s would result in two ballads, which he considered “the most technically sophisticated poems I have attempted ” (NF, 139). Wilkinson reads a letter poem written to Roger Hilton in 1966, and then given in extract to Clodd, in dialogue with his later elegy to Hilton, LINES ON ROGER HILTON’ S WATCH. Then there are those works that could stand as poems in their own right, but which Graham opted neither to publish nor to discard. Bedient looks at five of these, reading them within the broader gestures and concerns that motivated Graham throughout his oeuvre.

Graham’ s writing process often involved automatic writing exercises, blending surrealism with pastiche-homage to Finnegans Wake–era Joycean wordplay, and Powell provides a reading of one particularly formative piece of such writing. But Graham also increasingly employed what he called “automatic drawing ” (NF, 85): standalone watercolors, abstracts, portraits, sketches within his notebooks, and postcards to friends, reaffirming the epistolary ethos that so underpins Graham’ s poetics. We reproduce a large array of such drawings, and of three major types. There are portraits of Graham from painter friends of his: Alan Lowndes, Hyman Segal, and William Featherston. In addition to these, our selection includes handmade postcards he gave to friends, and illuminated letters. But before that, we include materials from two extraordinary notebooks that Graham made over the course of the late 1950s to the early 1970s. Of these, the first is an artist’ s book, given to Skelton in October 1974, but dated, according to Graham’ s inscription, from “early days at Gurnard’ s Head ” (he lived in a coastguard’ s cottage on the north Cornwall coast, overlooking Gurnard’ s Head, from 1956 to 1962; the earliest dating of a drawing in the book is in fact 1955). In this, Graham paints and writes over a medical textbook he had picked up in a secondhand bookshop: Artificial Limbs: For Use After Amputation and Congenital Deficiencies by F. G. Ernst (1923). It is a genre-defying production that predates Tom Philips’ s A Humument by a decade.

The second notebook also superimposed work over found materials: this time the book in question was the fiftieth anniversary publication of the Rockefeller Foundation, immodestly entitled Toward the Well-Being of Mankind (1963). Here Graham did not always draw or paint directly onto the pages, but would glue drawings, automatic writing exercises, and drafts of poems: we include an early sketch of what would become the second lesson in JOHANN JOACHIM QUANTZ’ S FIVE LESSONS. The draft includes extended reflections on the “terrible shapes of silence ”—and when the speaker says “That is your medium, ” the relation between flautist and poet is made far more explicit than in the final poem. Indeed, it is striking that Graham will quite performatively step back from this reflection in his finished version. The draft reads:

They hunt affection. Differently

They all are silence. Don’ t frighten them off.

That is your medium. They are our necessary, dear

Boundaries, as wild as we would have them.

Graham’ s published “lesson ” replaces all this with a laconic: “Enough of that ” (NCP, 229).

This points to a fundamental, fascinating tension between the Graham of these sketches, drafts, approaches, and the Graham of the finished works. Where the poems published during his lifetime are taut, honed art objects, the archive shows a maker delighting in provisionality, instability, working at an aesthetic characterized as much by its maximalism as its “whole / Formal scheme. ” This allows us to see new affinities in Graham’ s writings, to inscribe him into different lineages, appreciate different artistic achievements.

When Graham entitled one of his great meditations on language APPROACHES TO HOW THEY BEHAVE, “approaches ” seemed particularly apposite to describe his poetic practice, where similar motifs and figures recur in new configurations, in order to make sense of the abiding questions his poetry continually poses—“the difficulty of communication; the difficulty of speaking from a fluid identity; the lessons in physical phenomena; the mystery and adequacy of the aesthetic experience; the elation of being alive in the language. ” This happens within the fifteen sections of APPROACHES, but also across Graham’ s oeuvre—and, as we have discovered, throughout his archive, with its preliminary approaches to questions, places, and images that would later take definitive, published form, or else be left to provisionality and posterity. To these approaches our special issue adds further approaches, not by Graham but to Graham: the poems of Denise Riley, Gavin Selerie, and Rachael Boast which approach Graham through philosophic dialogue, through reworked motifs, reimagined subjects; and the critical “approaches ” of W. N. Herbert, John Wilkinson, Lavinia Singer, Eric Powell, Sam Buchan-Watts, Hannah Brooks-Motl, Jeremy Noel-Tod, and Calvin Bedient.

As already noted, Graham’ s reception thus far has been, in the UK at least, that of a “poet’ s poet ” par excellence. With unfortunate irony, he had indeed predicted such a fate sixty years ago. In a draft to his 1958 poem THE DARK DIALOGUES, in a phrase later taken up in his 1964 elegy THE THERMAL STAIR, he wrote:

I hope I do not write

Only for those few

Others like myself

Poets maimed for the job.

It may well be that, given Graham’ s continual attention to the dynamics of making, the possibilities and obstacles of communication, and “the elation of being alive in the language, ” he was always going to appeal to poets especially. But what emerges from this special issue is a portrait of creative activity that outstrips the finished poems, and one characterized by its sociability and its play, as well as a searching intellectual sensibility and technical virtuosity. If for various reasons Graham’ s work has remained for the most part in obscurity, it speaks with perhaps greater clarity and cogency today than ever before.