Chicago Opera Theater, Everest/Aleko

Reviewed by Sam Mellins

Music by Joby Talbot. Libretto by Gene Scheer. November 16-17, 2019.

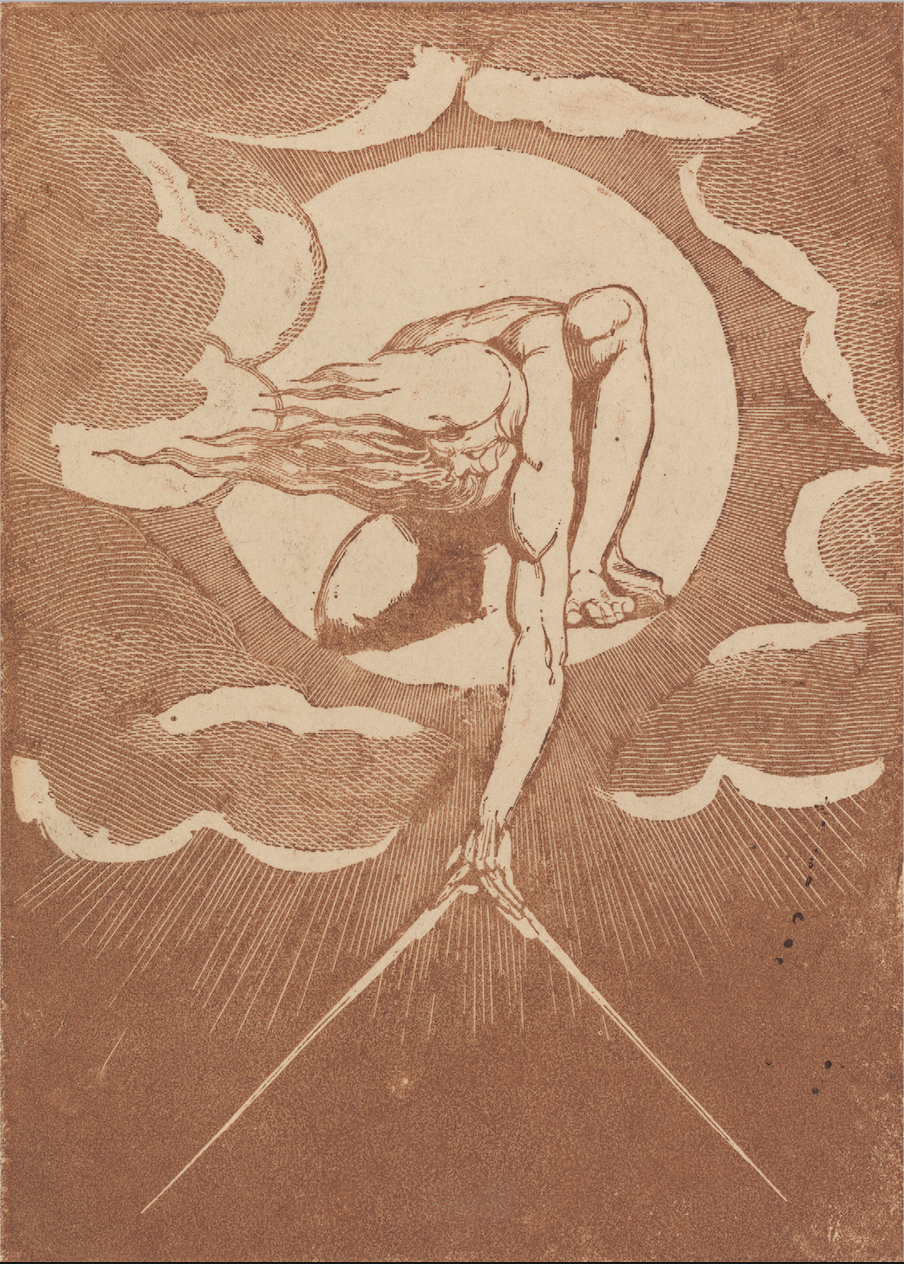

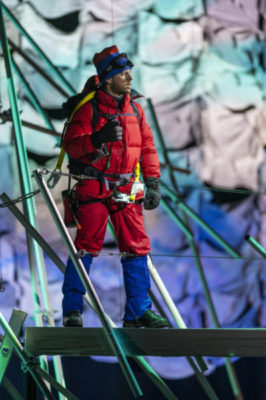

Climbing Everest is easy. It’s coming down that’s the hard part. Or so we would be led to believe by Everest, a one-act operatic retelling of the May 1996 Mount Everest Disaster, in which eight climbers died after being hit with a freak storm during their descent from the peak. Composer Joby Talbot and librettist Gene Scheer’s work provides the material for a deeply emotionally felt account of the tragedy, which Music Director Lidiya Yankovskaya and the Chicago Opera Theater (COT) did not fail to deliver.

Under the musical direction of Yankovskaya, the COT has made a name for itself as one of the foremost national champions of new opera, with last season’s critically acclaimed Moby Dick establishing the company as a major player in this role. The trend continues with Everest, in which a brilliant score, captivating performances from the soloists, and colorful and confident playing and singing from the orchestra and 140-member Apollo Chorus combined to produce a stunning artistic achievement.

The opera zeros in on the stories of three mountaineers as their attempt to climb Everest (minimalistically and effectively represented by a series of ladders and suspended platforms) becomes fatal as a result of the storm and the climbers’ poor decision to continue climbing a full two hours after the appointed descent time of 2:00 P.M. As the expedition spirals into chaos, members of the mountaineers’ families emerge on stage for conversations with the beleaguered climbers. These conversations are both real and imagined: Beck Weathers (Aleksey Bogdanov) hallucinates speaking with his young daughter (Anna Lorenzo) back home in Texas, and expedition leader Rob Hall (Andrew Bidlack) is patched through by the crew at base camp for a possibly final conversation with his pregnant wife (Zoie Reams) in New Zealand. By the end of the opera, Rob Hall and climber Doug Hansen (Zachary Nelson) are dead of hypothermia, while Beck Weathers manages to make it back to Base Camp, critically frostbitten but alive. Not one’s usual operatic fare in terms of plot, but nonetheless (or perhaps precisely because of its eschewing the melodrama and cartoonish villains more familiar to the genre), the narrative comes across as entirely compelling.

The brightest star of the production was Talbot’s music, which is deeply creative and often intensely moving. His score contains much that is thoroughly tonal and melodic, but Talbot also mines the orchestra for non-melodic “effects,” like the sliding violins, trilling piccolo, thrumming bass clarinet, and pulsating tom-toms evoking the howling winds and shifting ice of the Everest summit. Yankovskaya made the most of Talbot’s work, allowing the colors of the choral and orchestral writing to shine through, while ensuring that the soloists were never overpowered by the sometimes-copious forces arrayed against them. Perhaps there’s more going on here than simply successful conducting—in this opera especially it seems important that the individual human voice is not drowned out, even in the face of death on the impersonal slopes of the Himalayas.

Scheer has refreshing ideas about what a modern libretto can be: all of the characters speak in the language of everyday conversation (when the house lights came back up, my friend turned to me with a shocked expression and said “they used ‘fuck’ in an opera!”). The chorus was more of a mixed bag. They were at their most effective when Scheer allowed them to participate directly in the action of the plot, counting down the minutes until sunset, or speaking directly to the soloists in the fashion of Ancient Greek tragedy. In an opera essentially about the inner emotional worlds of three men in mortal danger, the chorus give the soloists opportunities to answer questions like “Were you scared?” providing an additional and meaningful look into the climbers’ psyches. The chorus was less well-used when they soliloquized in a more high-flown and philosophical lexicon which felt largely out of place amid the generally conversational tone of the libretto. Their pontifications were all the more unnecessary because the libretto demonstrated a real ability to deal with serious issues precisely without waxing overly philosophical. One of the best dramatic moments in the opera was when Beck Weathers sang, in common parlance, about the crushing depression he faced at home, and how only in climbing mountains could he find relief. Sheer deserves credit for recognizing that no grand verbiage is necessary for serious drama or depth. The extremity of the setting, and the mountaineers desperate will to live (captured by Sheer thanks in part, no doubt, to his forty hours of interviews with those associated with the tragedy) do all the work necessary to make Everest the stuff of intense theater.

Welcoming two of the three protagonists to the ranks of the Everest dead at the conclusion of the opera, the chorus sings, “Since 1922, our dreams have been woven from elegies,” a reference to the first abortive attempt by a British-led expedition to climb Everest. Talbot and Sheer’s work, by turns tragic, hopeful, and elegiac, is a deeply thought-out contribution to these dreams.

Aleko, written in two weeks by a nineteen-year-old Rachmaninoff as his final composition exam at the Moscow Conservatory, certainly had a tough act to follow. Despite able performances from the cast and the A&A Ballet, the traditional Romanticism of Rachmaninoff’s score felt more than a little anticlimactic after the exhilarating freshness of Everest. Nonetheless, there were some high points: the duet between Zemfira (Michelle Johnson) and her nameless lover (Andrew Bidlack) contained the most beautiful music of the opera, the hulking Aleko (Alexey Bogdanov) presented an easily loathable villain, and lush passages in the strings throughout the work revealed the man who would soon begin writing his great piano concertos and symphonies. And, if nothing else, COT and Lidiya Yankovskaya deserve credit for bringing a new work to the Chicago stage—though it was written more than a century ago, the work has never before been performed in this city.

COT returns to the stage at the Studebaker Theater in February with the world premiere of Dan Shore’s Freedom Ride, a COT commission.

Andrew J. Diamond, Chicago on the Make: Power and Inequality in a Modern City.

University of California Press, 2020. 432pp. $29.95.

Reviewed by Bo McMillan

It is with apt timing that Andrew J. Diamond’ s Chicago on the Make arrives, given how Chicago has lingered in recent popular discussion as the broken mirror from which New York and L.A. draw glamorous contrast, or as a focal point which our current president sees himself as an impassioned savior fighting back a fictitious national crime wave. (Violent crime has plummeted at the national level since the 1990s, despite a few recent upticks of violent crime in Chicago and other cities.) From Spike Lee’ s contentious Chi-Raq (2015) or the fetishized postindustrial white victimhood of Shameless (2011– ), to the oft-hyperbolized but still problematic murder rate that editorial offices love to sporadically pump when all other wells run dry (New York had about three times as many annual murders during the 1990s), Chicago seldom invites anything more substantial than bluster or shock-value extraction from popular pundits and misconstrued attentions from audiences without Chicago ties. (Lena Waithe’ s The Chi [2018– ] showed promise, however, and I am eagerly waiting for more.) Yes, Chicago is broken, and in a singular way. But when it comes to this city, which once competed with and even edged out New York for the national spotlight as the nation crossed into the threshold of the 20th century, too many have learned to fetishize the “what ” while frequently ignoring or egregiously simplifying the very important questions of the “why ” and “how. ”

Diamond’ s book, for anyone looking to actually understand the “how ” and “why ” of what has been called the most American of cities, does both of these concepts laudable justice. Arguing at its core that the history of modern Chicago singularly impacted—and perhaps even gave rise to—the implementation of neoliberal policies in the US, especially in its cities, Chicago on the Make combines a “play the hits ” version of Chicago’s history with refreshingly new analysis and insight crucial to scholars interested in urban studies and in the real national significance of Chicago.

While Adam Cohen and Elizabeth Taylor’ s American Pharaoh remains the standard for information on Mayor Richard J. Daley (1955–1976); Upton Sinclair’ s The Jungle stays the luridly entrancing read about Chicago’ s industrial past; and Natalie Y. Moore’ s The South Side joins Arnold R. Hirsch’ s Making the Second Ghetto among the key sources for exploring Chicago’ s racial divides (Eve Ewing’ s Ghosts in the Schoolyard [2018] is another recent addition to that canon), the benefit of Chicago on the Make is that it combines concise versions of these and other key aspects of Chicago’ s history into a greater historical narrative that traces them, in mosaic fashion, to the fragmented Chicago of today. As Diamond writes in the sprawling thesis:

Where this new history of Chicago diverges from most political histories of the American city in the twentieth century is in its effort to view the dynamics of inequality and demobilization as manifestations of a process of neoliberalization, which in the antidemocratic, political-machine context of Chicago advanced somewhat more rapidly and more aggressively than it did elsewhere. The term neoliberalization is invoked not merely to connote the implementation of a package of economic-minded policies that had inadvertent social and political consequences—such policies were in fact implemented and they did have important social and political consequences, especially in the early 1990s under Richard M. Daley. A more important dimension of the story of neoliberalizing being told here involves revealing how market values and economizing logics penetrated into the city’ s political institutions and beyond them into its broader political culture.

The claim is as massive as its length implies, but simpler than the jargon makes it seem. The term “neoliberalization ” tends to be capacious in its usage, but essentially Diamond’ s story tells as follows: 1) that the Chicago political machine’ s abuse of public power for patronage gain ensured political “quiescence ” and “demobilization ” at the local grassroots level, and so served as a method of increasingly turning city services and funds over to the whims of private and supposedly “economically minded ” interests, a method that culminated in the virtual partnership between Richard J. Daley’ s uber-mayoralty and downtown business in the mid-1950s; and 2) that this political foreground enabled his son Richard M. Daley to adapt the utterly deregulatory, free-market type of neoliberal practices, fully inaugurated by Ronald Reagan in the 80s, during his mayoralty from 1989–2011. To put it in Diamond’ s words: “While scholars like David Harvey have viewed the context of the mid-1970s as pivotal to the neoliberal turn, this history of Chicago views neoliberalization as a process that unraveled gradually and unevenly over much of the twentieth century. ” As a primogenitor, then, Chicago is an important place to look while seeking to better understand the emergence of American neoliberalism, as well as the consequences that neoliberalized municipal, state, and federal governments have since created and faced.

Whether or not Diamond manages to entirely defend that claim is subject to debate, especially when it comes to the primacy of Chicago’ s placement in his historical arc of American neoliberalism. True, the design of Chicago’ s city plans by business leaders, the privatization of its parking meters and garages, and its conversion of public schools into charter campuses are hallmarks of municipal neoliberalization, but they are not unique to Chicago—a fact which Diamond asserts time and time again: “in this, Chicago was and still is a lot like many other American cities. ” What is most important in his analysis, rather than an examination of the effects of neoliberalization itself, as the long thesis seems to suggest, is his focus on how Chicago’ s perfected machine politics brought neoliberalization to its most dramatic ends. After all, economizing logic can work to a city’ s social benefit if it indeed takes into consideration the city and all of the people who comprise it as investors and beneficiaries—for instance, as Patrick Sharkey maps in his book Uneasy Peace (2018), the funding of community organizations proves a far more economical and socially beneficial means of reducing urban crime than arrests and imprisonment. But in Chicago, as Diamond demonstrates, unchecked machine politics disrupted the nature of that balance and then magnified the break, producing solutions entrenched in a skewed system of values that took machine and business interests as the equivalent of city interests—not “economic-minded ” as in “economized, ” but “economic-minded ” as in “for the sake of my own financial well-being. ” Civil servants, empowered by the singular and virtual perpetuity of Chicago’ s Democratic Party, became self-servants in a way that continues to mark itself as distinct via its outright flagrancy (e.g., in 2019 the sprawling trash fire that has been Ed Burke’ s indictment), though the current national regime is doing its best to close that gap. Because of this, the book feels like more of an indictment of cronyism and the political-machine system perfected in Chicago than a critique of neoliberalization in itself.

No one seems to come out unscathed from Diamond’ s historical overview, and finishing the book, regardless of political orientation or preference, leaves one with the feeling of having just unfurled a scroll coated in an uncomfortable film of grease. Though the jarringly grand workings of Democratic handouts and patronage projects under the first Daley seem to get the most extensive lip service in the book, lengthy sections are devoted to more recent political events that don’ t have the comfort of residing in a dismissible past, and include among them extended discussions of how the kowtowing of mayors Richard M. Daley and Rahm Emanuel to business interests has left the city in a financial malaise. Other than serving as a means to track “neoliberal ” consequences from the time of Richard J. Daley straight to contemporary Chicago, Emanuel strikes another keynote in Diamond’ s book by serving as an anchor to discuss the uncomfortable business of Chicago politics and its relation to the rise of Barack Obama, a difficult task that the author handles with fairness and grace. Diamond discusses the benefits accrued almost entirely by business interests and white, upper- and middle-class residents while Richard M. Daley deployed Reaganite neoliberal policy to save the city from economic depression in the wake of deindustrialization: “In view of all the links between Daley’ s City Hall and Obama’ s White House, it would be hard to argue that the political sensibilities that suffused the Chicago success story of the 1990s and the first decade of the twenty-first century did not shape the Obama administration in significant ways. ” Michael Eric Dyson’ s work The Black Presidency hammers home the parallels. For a quick and nonencompassing survey, during the Obama presidency median Black household income dropped by 11.1 percent (double the rate of median white household income) while racial wealth disparities nearly doubled—with median white household wealth (around $110,000) settling at twenty-two times that of the median Black household (just under $5,000).

Obama grew within the Chicago political machine and it suffused much of his administration: from Emanuel to William Daley (Richard M. Daley’ s younger brother, who took over as White House Chief of Staff following Emanuel’ s departure and recently made a losing bid in the Chicago mayoral election), David Axelrod (advisor and campaign strategist to both Daley and Obama), Valerie Jarrett (Richard M. Daley’ s former chief of staff, and Obama advisor), and even Michelle Obama (a former assistant to Richard M. Daley and a Chicago planning official). This, as Diamond notes, does not discount the enormous strides, both political and symbolic, made by Barack and Michelle Obama, but calls into question a narrative of that moment that can sometimes fall into a partisanship-inclined form of uncritical hagiography, one that bears dangerous political implications for Chicago politics and the politics of the nation. Diamond grants the fact that for Obama to have opposed the Chicago Democratic Party would have been “political suicide, ” and repeats the common refrain of how Obama’ s personal beliefs stood opposed to many machine efforts. These necessary reminders of how politics are a dance of compromise also underline the fact that it is and has been a dance in which Obama and other African American political figures hold an incredibly fraught position because of their race, one which often leaves them vulnerable to hard concessions.

Diamond also draws a distinction between Obama and other Black political machine figures in Chicago who Diamond holds more closely complicit in the city’ s broken neoliberalized history. Obama’ s tale, as Diamond writes it, is instead more closely related to the story of Harold Washington, who, in Diamond’ s book (as with many Chicago histories), is the one person who rises from the muck unsullied due to his hard, anti-machine campaign:

Black mayors had headed major American cities since 1973, when Tom Bradley was elected in Los Angeles, Coleman Young in Detroit, and Maynard Jackson in Atlanta, but this was Chicago—the city with the second largest black population in the United States, where the saga of black struggle was particularly well known. Moreover, it was an event of great significance for the black diaspora—of lesser magnitude, of course, but not unlike the election of Barack Obama as president in 2008. Indeed, Washington’ s election was made possible by a breathtaking show of black solidarity and, as such, was a source of inspiration for blacks all over the world.

Hope, a parallel to that inspiration, is what accompanied and flowed from a political figure who once doxed alderman Eugene Sawyer for caving to machine interests across the color line following Washington’ s death, as captured in Obama’ s book Dreams from My Father. Yet, the recent fiasco of choosing a location and setting a community benefits agreement for the Obama Presidential Center is one example of how the machine has since taken its pound of flesh from Obama’ s legacy.

In a way that has become sadly daring as of late, Diamond collapses illusorily neat equations of partisanship and sociopolitical values by resurfacing an oft-elided narrative that rubs against the grain of neat partisan indexing. “A rose by any other name would smell as sweet ”—a cash-strapped public education system, police corruption, segregation, and crony contracts engineered by any party, as Diamond shows, would still reek of shit. It’ s a jarring and necessary reminder for everyone: good politics is not just party politics. And, to invoke The Jungle, it is rough, but imperative, to realize how the sausage of policy and political legacies gets made.

While neoliberalization is the buzzy framework through which Diamond outlines this point, his focus on the function of Chicago’ s machine politics forms the nexus of this historical case study into why and how “economic-mindedness ” can fail municipal governments—especially those singularly corrupted by an unchecked political juggernaut—and, from there, carry national implications, as such political machinery spreads from city to city and even bubbles up to the federal level. Remember, à la Diamond, Chicago “was and still is a lot like many other American cities, ” and it in fact may be the most American of cities. Du Bois captured it in his darkly satirical take on the political machines of 1920s Chicago in his novel Dark Princess, and it is as true now as it was then: “There was war in Chicago—silent, bitter war. It was part of the war throughout the whole nation… ”

This Review is in Chicago Review 62.4-63.1/2

Manual Cinema, No Blue Memories: The Life of Gwendolyn Brooks

Reviewed by Marissa Fenley

Written by Crescendo Literary (Eve L. Ewing and Nate Marshall). Music composed by Jamila Woods and Ayanna Woods. Directed by Sarah Fornace. Premiered in Chicago, November, 2017.

The Chicago-based performance collective and production company Manual Cinema amplifies the theatricality of attending the cinema by creating “live films ” onstage with use of overhead projectors, live-feed videos, hand-cut puppets, silhouetted actors, and original live musical scores. While the audience watches Manual Cinema’ s puppeteers, actors, and musicians create the various layers of their piece, the resulting images of their carefully choreographed shadow puppetry are displayed on multiple screens above them. The puppet company typically tells stories without spoken dialogue, where narrative context either appears in written form on screen or in accompanying lyrics. The novelty of their innovative theater is thus met by nostalgia for older media, such as the familiar classroom standby, the overhead projector, or the classic aesthetics of silent film. In showing both the process of manually creating their “cinema ” and their polished multimedia scenes, Manual Cinema replicates a paradox of our contemporary media world. They deliver the seamlessness of popular cinema and TV, where the coherent, pixilated aesthetic of the screen is expected to present polished and palatable narratives, while also ripping open those seams, an aesthetic practice long familiar to the avant-garde. The audiences of Manual Cinema can delight in a tightly crafted narrative without the expectation of being fully absorbed by its fiction.

The techniques long associated with method acting in both theater and film—in other words, the eruption of organic and spontaneous feeling that paradoxically comes from years of training and craft—is no longer located in the body of the actors, but in a series of magically coordinated technical elements: music, silhouettes, light, transparencies, and spoken, sung, and recorded text. The serendipity produced by seeing these elements conspire together is, like traditional approaches to acting, a product of masterful technique: the diligent timing and dexterity of the puppeteers, their well-crafted puppets, and the ingenuity of the musicians. Yet, by locating the illusion of theatrical invention outside the athleticism of the actors’ emotional recall and mimetic skill, Manual Cinema instead allows its audience to enjoy the pleasure of narrative while displacing the secret magic of their theater to the process of creating the world where that narrative lives as opposed to the believability of its players. Manual Cinema neither sanctimoniously preserves the aura of authenticity or “liveness ” traditionally attributed to the theater nor do they replicate the seductive veneer of the screen. Instead they offer their paper-cutout puppets and live-action silhouettes as a shadow medium that intercedes between the two: that which gives us both the pleasures of the crafted and the organic without placing these categories in false opposition. Manual Cinema’ s use of the incredibly malleable medium of shadow puppetry demonstrates how the use of an eclectic and diverse media landscape need not impede a practice of straightforward storytelling.

Manual Cinema’ s recent production No Blue Memories: The Life of Gwendolyn Brooks draws heavily on untheatrical material. The piece was commissioned by the Poetry Foundation for the Brooks Centenary and written by Crescendo Literary, a collaborative partnership between poets and educators Eve L. Ewing and Nate Marshall.† In fact, the name Crescendo comes directly from a Brooks poem, and their mission, “to create opportunities for artists to think meaningfully about what it is to be in community, ” is inspired by her legacy. No Blue Memories not only turns Brooks’ s poetic language into visual, scored tableaus; it reconstructs the story of her life from archival material housed at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. In many ways, this is a product of Ewing and Marshall’ s training; while intimately familiar with poetry, and Brooks’ s poetry especially, Ewing in particular also has a background in social science work and archival research. In fact, this show draws not only from the archives at UIUC, but Ewing’ s undergraduate work at UC Berkeley, where further materials on Brooks are held. Yet, the passive act of letter writing, the reserved quietness of Brooks’ s personality, and the abstract quality of poetic language are difficult to translate into theatrical action.

While No Blue Memories marks Ewing and Marshall’ s playwriting debut, through their collaboration with Manual Cinema they turned a scholarly endeavor into a dynamic and animated production that takes on characteristics of a live concert or music video—mediums far afield from what one expects of the pedagogical and readerly exercise undertaken in this piece. While Ewing and Marshall’ s work is largely text-based, Manual Cinema rarely uses text in their pieces, but rather uses almost exclusively visuals and sound to tell a story. And yet, Manual Cinema’ s visual and sonic medium has the unique ability to tap into formal features of pop culture that contain surprising opportunities for the poetic and pedagogical project of Ewing and Marshall’ s script. Their pieces not only deploy visual representations of rhythmic forms reminiscent of music videos, but in disclosing the makings of each performance, their techniques are also resonant with those of reality TV—a form that capitalizes on public exposure and scandal, moments where audiences are able to glimpse what goes on “behind the scenes ” of celebrity performances. No Blue Memories also used a sonic landscape to capture the different eras of Brooks’ s life. For example, the play takes its title from a 1948 Ella Fitzgerald song, “My Happiness, ” and Jamila and Ayanna Woods, who composed the show’ s score, deployed a wide variety of musical styles to mark the ways in which music differently shaped Brooks as a poet, educator, and Black woman.

No Blue Memories gives us intimate glimpses into the making of Gwendolyn Brooks—as poet and persona—but also the making of Gwendolyn Brooks the shadow puppet character—as a performative and academic reconstruction. In one scene we see a silhouette of Brooks talking into a phone against the backdrop of her book-lined living room. This scene alternates with a silhouette of her daughter, similarly situated against a projected backdrop of her own room, talking on the other line. Brooks asks her daughter to read back a letter Brooks has just dictated to her. (The letter is one of the documents uncovered by Ewing and Marshall in the archives.) Brooks has written to the publishers anthologizing her poems insisting that they include a broader spectrum of her work. As her daughter reads the letter back to her, Brooks insists that the words appear within their proper format. Her daughter begrudgingly confirms that she has, indeed, typed them out correctly; she narrates the various emphases and stylistic flourishes of Brooks’ s pen, from underlining to repetition to capitalization. In this way, one can see the archival process behind the development of the show: Brooks’ s letters, speeches, and poems appear within the narrative as textual artifacts. In fact, Ewing and Marshall were interested not just in individual letters but the way that letters as a form could represent different aspects of Brooks’ s teaching, craft, and legacy. They turn these static historical documents into dynamic theatrical events without erasing the evidence of the academic project behind their resuscitation.

Brooks was a poet writing out of two competing literary traditions: modernism and the Black Arts Movement, the former known for its formal experimentation and the latter marked by free verse and social critique. Much like Brooks’ s own divided poetic lineage, Manual Cinema’ s “live films ” dance between a similar split in aesthetic tradition. In No Blue Memories, Manual Cinema stays close to a biographical and socially inflected portrait of Brooks. They present her poems predominantly as artifacts that contain social observations of Chicago’ s South Side and Brooks as an ethnographer of her environment. When reciting “We Real Cool, ” Manual Cinema represents the seven pool players at the Golden Shovel described in the poem. On one slide, Brooks is shown hesitantly peeking into the bar as another projector opens on close-ups of the pool players’ faces, their pool cues, and a bird’ s-eye view of the pool table as the balls break. We are looking at the poem’ s content through the eyes of Brooks as an observer. However, once soul singer Jamila Woods comes center stage beneath the screen and sings an R&B rendition of Brooks’ s poem, we see a puppet Brooks dancing in the Golden Shovel beside the pool players. The music shifts the poem’ s function from documentary form to an account of Brooks’ s own interior experience. Woods becomes the voice of the poem, adopting the position of outside observer, while Brooks becomes the poem’ s subject. Manual Cinema powerfully deploys the different registers of their hybrid medium to recreate Brooks’ s own struggle over where to locate identity in poetry. Brooks’ s poetry complicates the division between aesthetic experience and poetic content. She is concerned both with how to document the specific conditions of Black urban life in Chicago and how to represent Black identity and the experience of Blackness more broadly. In slipping between different media, thus repositioning subjects inside and outside the frame of the screen, Manual Cinema is able to represent the uneasy relationships between the personal and the social, the public and the private, the interior and the exterior.

The hybridity of Manual Cinema’ s “live films ” is far more capacious than this self-description suggests. No Blue Memories does not simply combine live performance and film; it is also a work of archival research, poetry, music, dance, and, of course, puppetry. While breaking down traditional boundaries between media is a now familiar practice within experimental performance and the visual arts, Manual Cinema’ s ability to retain divisions between the media they use—as their narratives visibly jump from projector to live actors, to screen, to live musical performances—is essential to their unique aesthetic practice. They incorporate the transformations these narratives undergo as they move between media as integral components of the narratives themselves. It is this feature of their practice that allows Manual Cinema to accomplish several intersecting aesthetic goals: they replicate poetic form, offer social critique, reanimate biographical history, and deliver both the narrative pleasure of a carefully unfolding story and the synesthetic exhilaration of a multimedia performance.

This Review is in Chicago Review 62.4-63.1/2

Big Camera/Little Camera

The Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, February 23 – May 5, 2019

Reviewed by Luke A. Fidler

Laurie Simmons, Brothers/Horizon, 1979. Cibachrome; 5 ¼ x 7 in. Photo courtesy of the artist and Salon 94, © Laurie Simmons.

In the original ending of the classic film noir Kiss Me Deadly (Robert Aldrich, 1955), the femme fatale figure opens a box containing some unspecified nuclear material. The protagonists, played by Maxine Cooper and Ralph Meeker, stagger through surf and sand as the Malibu house behind them burns. Flashes of light irradiate the night in an uncanny scene that reads as a deliberate reference to Hiroshima, Nagasaki, and the impending threat of nuclear disaster. The meaning of the “cleansing, combustible element,” as critic Alain Silver put it, is drawn out in the film’s “appropriately hellish” lighting.[1] By the eighties, however, such earnest juxtapositions of war and American domesticity looked dated. In the wake of works like Martha Rosler’s House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home series, the definitive exemplar of this strategy, artists tried to find new ways to represent the relationship between bourgeois America and manmade catastrophe.

The Museum of Contemporary Art’s recent comprehensive retrospective of photographer Laurie Simmons, Big Camera/Little Camera, presents an artist who has consistently returned to similar themes over the decades. Beginning with Simmons’s earliest small-scale photos and moving chronologically through her oeuvre, the show includes many of her most famous works, as well as judicious samples of her career’s major phases. It concludes with some recent projects, showing how she has developed, refined, and occasionally got bogged down in a handful of key themes. Long a sharp-eyed critic of fifties visual culture, she deals with big social issues through the visual language of the everyday (the language, that is, of a very historically particular, American middle-class “everyday”).

For example, Simmons yokes atomic disaster to everyday life in a telling print from her Tourism series that brings to mind the finale of Kiss Me Deadly. Tourism: Bikini Atoll (1984) shows four female figurines watching a nuclear test explosion. One leans back in surprise while her companions press eagerly forward, the leftmost figure tossing her ponytail with such eagerness that it’s difficult to read anything like horror or recoil. These are middle-class Americans enjoying the spectacle of imperial violence. But, especially when read in light of the works arrayed in the retrospective, they have none of Rosler’s polemical bite. For Simmons it’s not really a fundamental problem that Americans treat disasters in foreign places like Bikini Atoll or large-scale violence against foreign populations as spectacular tourist treats; the artist, mother of Lena Dunham, turns out to traffic in some of the same problematic white feminism as her daughter and to embody a theatrical, bourgeois politics. Her camera celebrates the gaze of white, middle-class women who suffered patriarchal repression and the scopophilic male gaze, to be sure, but who also dependably endorsed American exceptionalism and played up racial hierarchies ad nauseam.[2] If these issues show through most clearly in her portrayal of women from the immediate postwar period, they also crop up in her recent work where the few women of color inevitably appear as sexualized objects, props for a clumsy critique of the pornography industry.

Simmons is best known today for her pictures of animated objects. Beginning in the 1980s, she added legs and arms to houses, handbags, cameras, and guns, sometimes using elaborate costumes and props. The retrospective has a good sample of these works and, by placing them alongside her later works with dollhouses and ventriloquist dummies, the curators show how she developed strategies for exploring these odd human surrogates. Critics have read her interest in dolls and animated figures in light of the talking things that populated contemporary TV shows like Pee-wee’s Playhouse, but Simmons also gave her work a political slant.[3] “Conceptually, I loved the notion of ventriloquism,” she says, “men speaking through surrogate selves and not having to take responsibility for their thoughts or actions.”[4] In one of her oddest and most compelling series, she commissioned a dummy of herself and photographed it surrounded by male dolls. Does the artist seize the masculine power to speak without consequences for herself? Can a female dummy exercise that power with all the force of a male one?

Other works focus more explicitly on the middle-class home. The Underneath series (1998) inserts domestic scenes between the legs of anonymous women, all made with the glossy Cibachrome process that renders colors boldly garish. House Underneath (Standing) shows a woman lifting a white dress to reveal a single-family house replete with garage and an idyllic surround of grass and trees. The house sits on a slightly warped mirror, giving the viewer a voyeuristic glimpse up between the subject’s thighs. The photographs, rendering women as colossi, reference the ways that domestic mothers were vilified as well as worshipped in the forties and fifties. Philip Wylie’s widely read Generation of Vipers (1942) warned against “the destroying mother” who, among other things, dominated and softened husbands and sons.[5] Simmons’s work is a tongue-in-cheek response to this pervasive image, ironizing it by literally staging the massive mother.

But if Simmons acutely identifies and pictures the complex gender relations that governed bourgeois domesticity in the postwar period, pointing out just how strangely sinister that world really was, she looks less acutely at other issues. Her recent works look at Japanese cosplay culture and sex-doll technology in ways that can only be described as Orientalizing. The Love Doll (2009–11) features an elaborately posed Japanese sex doll customized by Simmons herself. “She is a peculiarly Asian fantasy, exquisite and insanely well sculpted,” says the photographer, who recalls that she visited Japan desperate “to bring something back that would change my work.” Where she once trained a critical eye on her own childhood, she now turns to essentialist, exoticizing clichés, raiding other cultures for inspiration. “I was very aware of her Japaneseness when I first got her. She seemed to spring from that culture so completely.”[6] This shallow engagement shows through in the pictures; Simmons herself seems to restage the blasé attitude with which toy American women regard the rest of the world in Tourism: Bikini Atoll. Ultimately, this retrospective demonstrates how an artist’s perspicuity in one area doesn’t always translate well, mirroring the ways that white feminists precisely dissected their own conditions of oppression while turning a blind eye to the logics of race and empire that sustained bourgeois domesticity.

Notes:

[1] Alain Silver, “Kiss Me Deadly Evidence of a Style,” Film Comment 11, no. 2 (April 1975): 24-30. Jean-Luc Godard’s most recent film (Le livre d’image, 2018) cuts the finale of Kiss Me Deadly together with footage from atomic explosions, making the allusion explicit.

[2] See Laura Mulvey, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” Screen 16, no. 3 (1975): 6–18.

[3] Kate Linker, Laurie Simmons: Walking, Talking, Lying (New York: Aperture, 2005), 31.

[4] Ibid., 60.

[5] Philip Wylie, Generation of Vipers (New York: Farrar & Rinehart, 1942).

[6] Quoted in Stephen Frailey, “Love Dolls Don’t Love You Back,” Document Journal, October 19, 2018, https://www.documentjournal.com/2018/10/love-dolls-dont-love-you-back/.

July 2019

West By Midwest

The Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, November 17 – January 27, 2019

Reviewed by Brandon Sward

Gladys Nilsson, The Big Green Man, 1972. Collection Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, gift of Dr. and Mrs. Peter W. Broido. Courtesy the artist and Garth Greenan Gallery, New York Photo: Nathan Keay, © MCA Chicago.

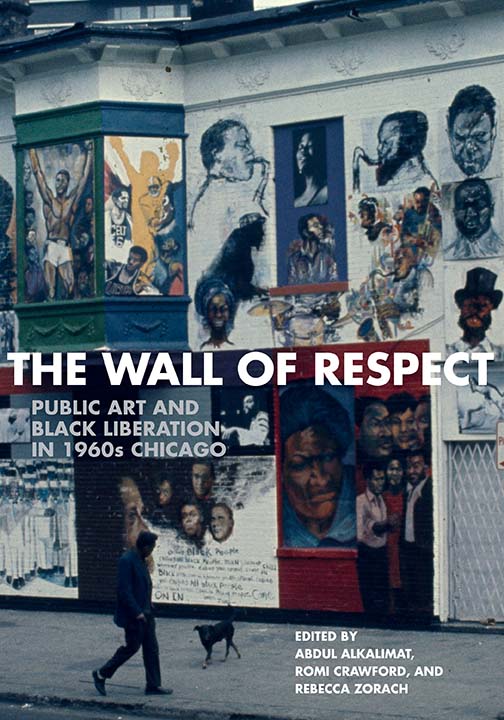

West by Midwest at the Museum of Contemporary Arts circles around two ironies. First, many of the artists we’ve come to associate with California came from the Midwest. Second, many of the artists we’ve come to associate with the Midwest spent formative time in California. We learn, for example, that the “Chicago Imagists” Gladys Nilsson, Jim Nutt, and Karl Wirsum moved to Sacramento in 1968, where they exhibited together at Adeliza McHugh’s Candy Store Gallery, which began selling art when McHugh couldn’t secure a food permit. We also hear of how Californian titan Ed Ruscha and his childhood friend took Route 66 from their hometown of Oklahoma City to Los Angeles in 1956. West by Midwest is expansive in its scope, ranging from Senga Nengudi’s pantyhose sculptures to Andrea Bowers’s activist art to an entire room dedicated to Mike Kelley’s quasi-archeological stuffed animal installation Craft Morphology Flow Chart (1991).

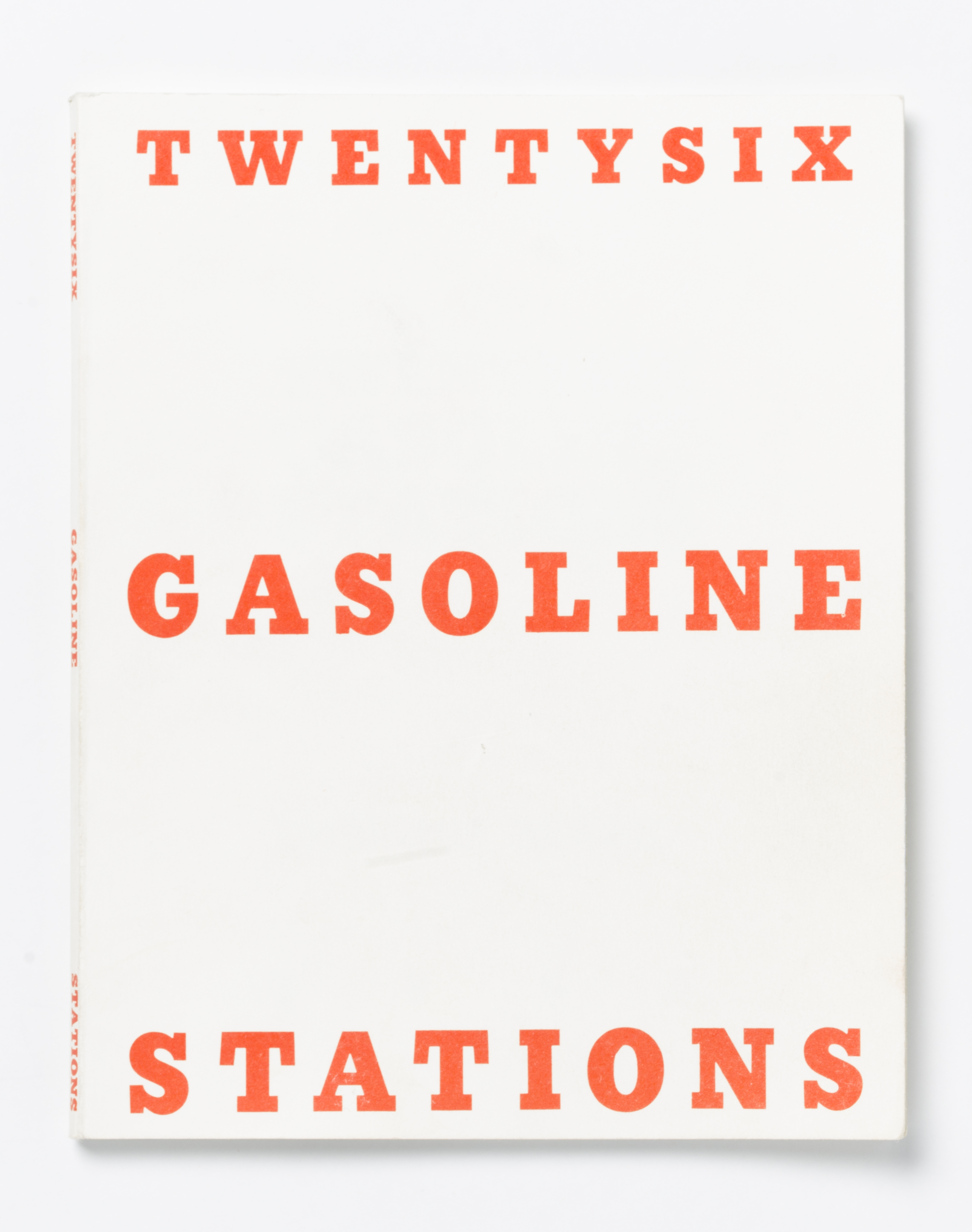

Edward Ruscha, Twenty-six Gasoline Stations, 1969. © Ed Ruscha Photo: Nathan Keay, © MCA Chicago.

Drawn in large part from the MCA’s collections, West by Midwest provides welcome respite from the blockbuster exhibitions that have become ever more common in the art world, as museums interpret each broken attendance record as a new challenge. The regional focus of West by Midwest has forced the MCA to move away from artists like John McCracken, whose impossibly smooth “finish fetish” planks are par for the course in showcases of mid-century Californian art. Nevertheless, the MCA continues to traffic in well-worn tropes, whether connecting Judy Chicago’s airbrush paintings to her time as an autobody student, or explaining Billy Al Bengston through surf and motorcycle culture. While these artists certainly had such experiences, their constant reference in discussions of Californian art reinforces stereotypes of the West Coast as the casual, anti-intellectual little brother of the serious, rarefied New York.

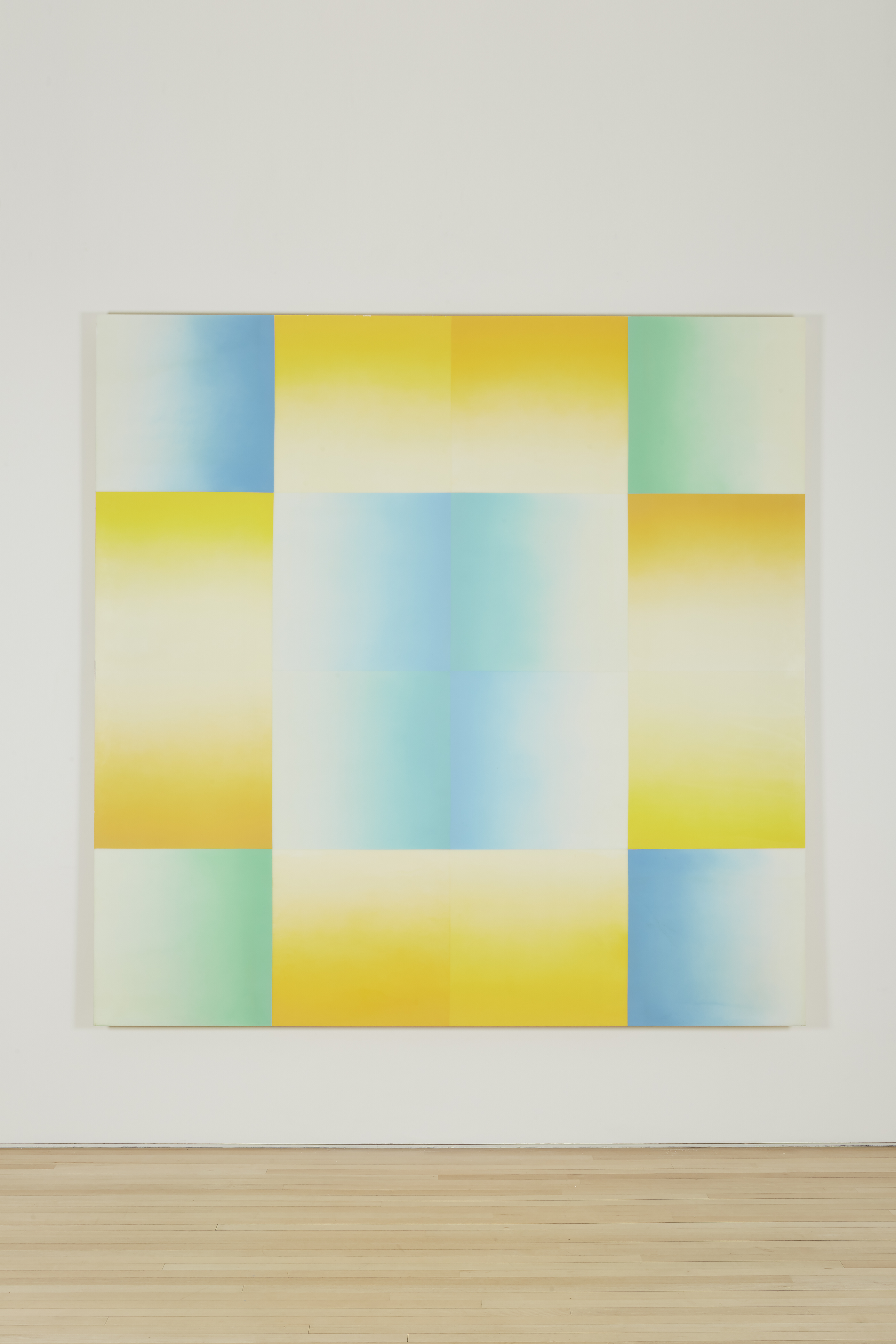

Judy Chicago, Sky Sun from the Flesh Gardens series, 1971. Courtesy the artist, Salon 94, New York, and Jessica Silverman Gallery, San Francisco © 2018 Judy Chicago/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

But if West by Midwest fails to breathe new life in Californian art history, this is only because it has a bigger goal in mind. As the introductory text puts it: “Western art history is often viewed as a neat succession of individual artists and their singular masterpieces. This narrative runs parallel to the American story of westward expansion, propelled by the idea of individualism and independence.” The radicality of West by Midwest lies in how it refuses this conventional paradigm; by foregrounding the network, curators Charlotte Ickes and Michael Darling trouble the very notion of artistic “genius” upon which the museum is predicated. If the discipline of Western art history has more or less progressed from one great white man to the next, a focus instead on the networks out of which these artists arise suggests the idea of genius itself might be more a reflection of our presuppositions than an accurate depiction of historical reality.

Melanie Schiff, Spit Rainbow, 2006. © 2006 Melanie Schiff. Photo: Nathan Keay, © MCA Chicago.

Perhaps the most interesting question raised by West by Midwest, however, is how the similar geographical origins of these artists affected how they approached California, a topic the exhibition doesn’t fully explore. Although the show explores movement in both directions between California and the Midwest, the lion’s share of attention is devoted to the artists who left their small towns for Los Angeles, fascinated by its colors and light, as well as its culture and politics, fixations that surface in their work. Consider, for example, the light play in Chicago-born Melanie Schiff’s Spit Rainbow (2006), complete with backyard orange tree.

To speculate on some Midwestern “essence” becomes dicey rather quickly, of course, but it’s unavoidable in West by Midwest. We tend to think of the Midwest as the wholesome core of America, its breadbasket, its cornfields. We could easily imagine that such a vision of the Midwest could stifle the artist, drawn to the coasts as surely as iron filings to a magnet. One can acclimate but never truly shrug off the past: a permanent outsider, the quintessential artist. But if these outsiders were true artistic geniuses, there would be no need for them to uproot, at least insofar as we think of geniuses as self-sufficient, self-contained, self-reliant. The fact that these artists nevertheless felt the need to be around their kind shows that more is going on, that talent lies dormant without conditions in which it can flourish.

February 2018

John Singer Sargent & Chicago’s Gilded Age

The Art Institute of Chicago, July 1 – September 30, 2018

Reviewed by Luke A. Fidler

Although recent scholarship has uncovered new and interesting dimensions to John Singer Sargent’s art, it’s hard to shake the suspicion that, for all his prodigious talent, Sargent was never much more than a gun for hire. [1] He courted wealth and his services were, in return, widely courted. Although he painted some publicly minded murals and genuinely experimental street scenes, his reputation continues to rest on his portraits of aristocrats, tycoons, and the nouveau riche from Europe to the United States. This ill-timed show at the Art Institute, built around the faltering conceit that Sargent and Chicago mattered to each other, does nothing to shake the idea of the painter as Gilded Age apologist. Despite some intriguing pairings and a lucid, well-researched catalogue, it lurches from misstep to misstep.

Born into a wealthy American expatriate family, Sargent trained under the French specialist in high-society portraiture Charles Auguste Émile Durand (known familiarly as Carolus-Duran). He came to notice for his artful presentation of beauty, a French critic declaring in the early 1880s that “all pretty women dream…of being painted by him.” [2] This period is represented in the Art Institute’s exhibition by a full-length portrait of Louise Lefevre from 1882 which exemplifies some of Sargent’s unconventional strategies, not yet developed into a signature style. Loose brushwork suggests the walls and furnishings of a dark interior, contrasting powerfully with the delicate modeling of the subject’s hands and features; a virtuosic set of slashes and shadows highlight the sumptuous folds and fabric of Lefevre’s blue dress; the strong white light complemented by the gathered curtains curiously overshadows the subject’s face; the composition is radically asymmetric; and the reflective glass in the upper left hints at the influence of artists like Diego Velázquez who, more than anyone before Manet, made the painted canvas a machine for examining the philosophical dimensions of looking.

Nineteenth-century portraiture generally functioned as a conservative genre, not only in the sense that it flourished as a form of conspicuous consumption by bourgeois and aristocratic elites, but also in the way it relied on well-established visual codes of class and gender to portray sitters. But where his teacher followed the customary formulas of the day, the young Sargent didn’t. His full-length portrait of Virginie Avegno Gautreau, known provocatively as Madame X, caused a real stir for its transgression of social mores. (The shock didn’t last; when the Friends of American Art tried to buy the painting for the Art Institute of Chicago in 1913, its erotic frankness would have lost its frisson in a world of newly ordered gender relations, and its commitment to figuration would have looked passé in light of the gauntlet recently thrown down by the Cubists.) Four Venetian genre scenes on display, small studies that ably showcase the artist’s eye for color, underscore the fact that Sargent’s work from the early 1880s had started to rearrange a whole host of received conventions.

But the bulk of paintings and charcoals in the exhibition were made after this period, and they demonstrate how his ambitions shrank. A dour portrait of Philadelphia millionaire Peter Widener from 1902 shows none of Sargent’s earlier painterly verve or gender-bending iconography. The few loose, black brushmarks overlaying the coat of his seated portrait of John D. Rockefeller from 1917 look like the forlorn vestiges of a forgotten heterodoxy. While Gilded Age millionaires did often patronize experimental art—the president of the American Sugar Refinery was lending the latest Impressionist pieces from his collection to the National Academy even as he brutally crushed strikes at his company’s factories—the show makes it clear that Sargent’s work began to reflect a certain kind of conservative taste as well as the financial arrangements that made his career possible. [3] A lifelong friend of industrialists such as machinery tycoon Charles Deering, whose 1876 portrait is on view, Sargent painted in sympathy with capital.

This sympathy is displayed even more garishly in Sargent’s paintings that aren’t straightforward, commissioned portraits. A Chicago millionaire bought The Fountain, Villa Torlonia, Frascati, Italy, and it became the first of Sargent’s works to enter the collection of the Art Institute in 1914. A sterling example of the painter’s wet-in-wet technique, it shows the English artist Wilfrid de Glehn and his American wife Jane, also an accomplished painter. Jane daubs at her canvas while her mustachioed husband reclines, eyes closed. This is the very picture of indolence, of two Anglo-American expatriates living on unearned wealth (de Glehn was the son of the Prussian aristocrat Robert von Glehn), of art as a pleasant pastime ennobled by the social status of its practitioners and patrons. Charles Deering himself took time off from his business concerns to paint seriously, and the show’s climax comes with Sargent’s deceptively casual depiction of Deering at the lavish Florida estate where he wintered. The elderly industrialist reclines in a cane chair, surrounded by palms and bathed in sun. In her catalogue essay, the show’s curator Annelise Madsen notes that the portrait was “undertaken informally as a result of the enduring bonds of friendship” shared by painter and sitter, with Sargent stopping off at the estate for a time after filling a commission from Rockefeller. [4] In spite of its dearth of critical framing, this exhibition shows, damningly, how the artist’s cozy relationship with the Gilded Age elite determined not just what he painted but also how he painted.

John Singer Sargent, The Fountain, Villa Torlonia, Frascati, Italy (1907). Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Madsen should at least be commended for not trying to shuffle Sargent’s sympathies out of view. If Chicago and Sargent really were connected during the Gilded Age, as the exhibition’s advertising copy proclaims, it could only be through the wants and wallets of the city’s superrich. (Much of the wall text quietly omits any mention of Chicago rather than risk straining the viewer’s credulity; Sargent only made two brief visits.) His collectors included Martin A. Ryerson, son of a lumber baron and famously the richest man in Chicago, and Charles Hutchinson, who notoriously cornered the market in wheat in 1888 while serving as the Art Institute’s president. These patrons wanted Sargent’s paintings both as pawns in their game of civic humanism, buying up art to display to Midwestern audiences in dire need of aesthetic education, and as testaments to their elevated status. The catalogue, which I suspect will prove indispensable to future analyses of fin-de-siècle art’s complicity with capital, carefully chronicles the ways these elite figures supported Sargent and put his paintings to use.

Of course, few issues are more timely than the relationship between art and capital, except perhaps the relationship between money and power. As the American political scene witnesses a retrenchment of anti-labor laws, soaring inequality, and the stunning convergence of business interests with elected office, it’s vital to revisit the legacy of the last Gilded Age when, as Alan Trachtenberg describes in a classic study, “an emergent form of ownership,” defined by power “distributed inwardly along hierarchical lines and outwardly in new social configurations and cultural perspectives,” spun society on its axis. [5] Chicago, roiled by police violence and corporate corruption, perfectly illustrated these new distributions of power and Sargent’s patrons like Deering, Hutchinson, and Ryerson perfectly illustrated these new kinds of owners. None of this social context appears in the exhibition, leaving attentive viewers to conclude that Sargent’s artworks probably functioned as prostheses of Chicago’s business elite but equipping them with no tools to make sense of what this might have meant. You’d be forgiven for leaving with a decidedly rosy image of the Gilded Age, a time of ruffles and ironic sailor hats.

A close reading of the Art Institute’s advertising campaign and ticketing policies for the show demonstrates that the museum means to celebrate this reading of art as luxury good, construing Sargent’s paintings as desirable commodities first and transparent visions of aristocratic life second. The show’s advertising apparatus is shockingly amenable to the forms of the ideology critique advanced by postwar theorists like Roland Barthes, Marshall McLuhan, and Raymond Williams, so much so that baffled friends texted me photographs of promotional posters for weeks, together with snippets from Mythologies. [6] Store windows on Michigan Avenue currently feature Sargent-inspired displays, from Bloomingdale’s to the Marriott to AT&T, with Macy’s perhaps the most outstanding offender. A pop-up bar at the Chicago Athletic Association featured a special event for pet owners: “Commissioned paintings during the Gilded Age weren’t always of moguls and divas, but also of beagles and dachshunds,” crowed the Facebook description, inviting the public to register by providing a pet photo that could be turned into a greyscale printed canvas. Dogs, owners, canvases, and “custom palettes” were invited to gather for cocktails.

And finally, Sargent’s distinctive portraits are covered with quotes culled from pop culture and plastered all over. Each iteration merits careful attention for the way it puts the elite art of the past in dialogue with the pseudo-democratic Öffentlichkeit of the internet. An Instagram ad overlays a woman’s stately head with the slogan “Yaaaaas Queen” and captions it with the words “OUTFIT OF THE DAY” and three fire emojis. The phrase, originating in queer communities of color, has now devolved to a form of digital blackface, part of a lexicon freely used by straight white consumers of popular culture. [7] “Gold Is the New Black” accompanies a detail from La Carmencita, an unsubtle allusion to the Netflix drama that chronicles life in a woman’s prison. “Damn Daniel” overlays the head of Sargent’s portrait of Augustus Saint-Gaudens’ ten-year-old son, referencing the popular meme in which one Californian teen compliments another. The marketing campaign trades on the fact that conspicuous consumption is a major form of public entertainment these days (think of Rich Kids of Instagram, Keeping Up With the Kardashians, the obsession with royal weddings), and that such entertainment depends on fantasies about participation; when the media reported that Kylie Jenner was close to becoming a billionaire, her fans tried to crowdfund an extra $100 million to push her over the edge. While the popular literature of Sargent’s Gilded Age saw an explosion of rags-to-riches tales, trading on the fantasy of becoming rich, these documents of our new Gilded Age ironize the impossibility of social transformation. I’ll never be a millionaire, but I can gorge myself on Kim Kardashian’s most intimate moments and debate the merits of her extravagant purse purchases. By analogizing the luxurious lives of Chicago’s bygone elites to the contemporary spectacle of inequality, and by analogizing the format of painting to the eminently accessible world of social media, these promotional images naturalize exploitation in the past and present alike.

“Promotion,” as the critic Harold Rosenberg presciently observed in 1968, “has become the vital center of aesthetic discourse.” [8] The advertising campaign supplies a dominant interpretive context for the show, filling the vacuum opened by the bland wall text and turning Sargent’s paintings into nostalgic icons—to borrow John Vlach’s felicitous description of plantation imagery—of wealth. [9] Nonmembers pay a hefty additional charge to enter the show, on top of the museum’s standard entrance fee which runs to twenty-five dollars for an out-of-state adult, despite the healthy array of corporate sponsors and the distinct lack of blockbuster loans that usually drive up special exhibition prices. (I set aside La Carmencita, lent by the Musée d’Orsay, which could only be called “blockbuster” if you squint hard.) There’s something deeply unsettling, in the era of President Trump, about asking Chicagoans to pony up extra cash to inspect a set of luxury commodities that aggrandized, and were owned by, the opulent figures who profited so handsomely off the working poor a century ago. But this demand squares neatly with the ideology underlying the marketing campaign; the middle class should fund and enjoy the spectacle of their own subjection.

Let me be clear. I’m not criticizing the Art Institute for capitulating to the pressures that all institutions face in the neoliberal age. As Matti Bunzl notes in his ethnography of the contemporary art museum, instead of seeing a “failure of nerve” in these nakedly anti-intellectual, ostensibly democratizing moves, we should probably see “a set of strategies devised to persist through a particular economic and cultural moment.” [10] Museums have to survive. But the Art Institute has made a damning set of choices about how to display and market Sargent’s work, which, the admirably historicist catalogue aside, rehearse a set of neoliberal commitments to the primacy of capital and exalt the old order of wealth.

Notes:

[1] See especially Alison Syme, A Touch of Blossom: John Singer Sargent and the Queer Flora of Fin-de-Siècle Art (Pennsylvania State University Press, 2010).

[2] Quoted in Juliet Bellow, “The Doctor Is In: John Singer Sargent’s ‘Dr. Pozzi at Home,’” American Art 26.2 (2012): 43.

[3] Michael Leja, Looking Askance: Skepticism and American Art from Eakins to Duchamp (University of California Press, 2004), 116.

[4] Annelise K. Madsen, “Second City Sargents: The Collectors Who Built a Sargent Legacy for Chicago,” in John Singer Sargent and Chicago’s Gilded Age (New Haven and London: The Art Institute of Chicago; distributed Yale University Press, 2018), 100.

[5] Alan Trachtenberg, The Incorporation of America: Culture and Society in the Gilded Age (Hill and Wang, 1982). Analysts like Larry Bartels have famously argued that we’re living through a “new Gilded Age.”

[6] For works that deal specifically with advertising, see Roland Barthes, Mythologies, trans. Richard Howard and Annette Lavers (Hill and Wang, 2012); Marshall McLuhan, The Mechanical Bride: Folklore of Industrial Man. (Vanguard Press, 1951); Raymond Williams, “The Magic System,” New Left Review 4 (1960): 27–32.

[7] Lauren Michele Jackson, “We Need to Talk About Digital Blackface in GIFs,” Teen Vogue, August 2, 2017, https://www.teenvogue.com/story/digital-blackface-reaction-gifs.

[8] Harold Rosenberg, “Art and Its Double [1968],” in Artworks and Packages (University of Chicago Press, 1982), 19.

[9] John Michael Vlach, The Planter’s Prospect: Privilege and Slavery in Plantation Paintings (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002).

[10] Matti Bunzl, In Search of a Lost Avant-Garde: An Anthropologist Investigates the Contemporary Art Museum, (The University of Chicago Press, 2014), 7.

August, 2018

Remembering 1968

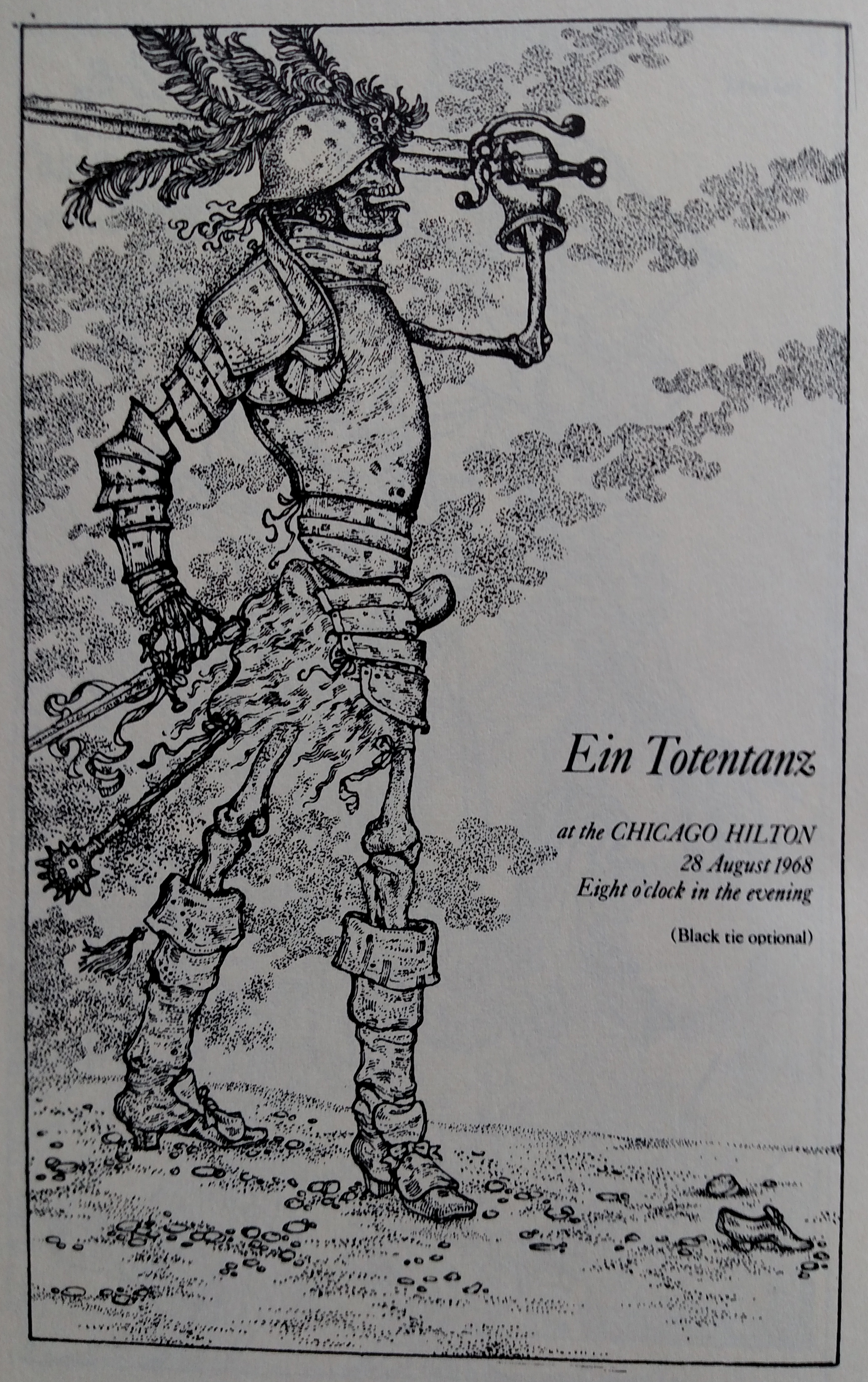

“Ein Totentanz” drawing by Virgil Burnett. Chicago Review 20.4/21.1.

This month marks the fiftieth anniversary of the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago (August 26–29), during which the Chicago police, reinforced by the National Guard, violently assaulted protesters gathered in Grant Park. The roughly 10,000 protesters were vastly outnumbered by the armed forces, which included 12,000 policemen, 5,000 members of the National Guard, 6,000 soldiers, including the 101st Airborne, and 1,000 undercover agents that infiltrated the protesters and possibly instigated the violence.[1] Richard Vinen writes that the police put lead shot in their gloves prior to the confrontation and “sprayed teargas with such abandon that Hubert Humphrey could smell it in his room on the twentieth floor” off Michigan Avenue downtown.[2]

The protests brought together various groups—Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), the Black Panthers, the Youth International Party (Yippies)—all united in opposition to the Vietnam war. The Yippies, more joyous and ludic in their resistance than some, decided that they would nominate a pig for president. They went into the country outside Chicago and bought a pig, which they named Pigasus, and scheduled a rally and press conference on what is now Daley Plaza (then the Civic Center), by the Picasso sculpture. The stunt led to the arrest of the “Chicago Seven,” as well as Black Panther Bobby Seale, who all stood trial in 1969 on various charges, including incitement to riot.

Last Thursday at Maria’s in Bridgeport, a theatrical reenactment of these events, “Flight of the ‘Pigasus,'” was staged as part of a series of events to mark the fiftieth anniversary of 1968, “68 + 50.” Planned by former CR fiction editor Paul Durica, now Director of Programs for Illinois Humanities, the reenactment condensed the moment of the trial and the original rally nominating “Pigasus for President,” with actors portraying the events off to the side of the “courtroom” as they came up during testimony, complete with a live pig.

The performance began with musician Phil Ochs, played by Bill MacKay, on the stand. As he was interrogated and gave his account of the events, they were acted out on the side by a group of actors dressed up as the Yippies. An interesting twist came in the middle, however, when the reenactment broke from the historical record to call living participants to the stand to give their actual eye-witness stories. Judy Gumbo, wife of Yippie Stew Albert, took the stand and, when sworn in with the Bible, said: “Where is God, and what is truth?” Gumbo also claimed that Pigasus was a woman and would therefore have been the first woman president had the police not intervened. James Lato then took the stand and recalled going to find the ugliest pig they could get, and having to fork out the $20 to buy it because Jerry Rubin and the other Yippies didn’t have any money. Finally, Vince Black (formerly Blakey) took the stand and recounted the moment when the pig was given to him on a leash in the plaza and went wild. When the police arrested Rubin and Albert, they supposedly quipped: “Sorry boys, the pig squealed.” Black contradicted the commonly repeated denouement that Pigasus was given to the Humane Society and lived happily ever after on a nearby farm; instead, Black claimed to have heard from a connection within the CPD that they had a BBQ and—well, you know what happens to pigs at BBQs. After he said this someone in the audience began yelling: “Cannibals! Cannibals!”

“Flight of the ‘Pigasus'” at Maria’s in Bridgeport, August 28, 2018. Bill MacKay as Phil Ochs singing “I Ain’t Marching Anymore.” Photo by Eric Powell.

The event concluded with another revision of the historical record; Phil Ochs had tried to sing his protest song “I Ain’t Marching Anymore” on the stand, but was ushered out of the courtroom. Instead, at Maria’s he stood right up there on the stand and sang the song, the audience happily singing along. It was a creative way to commemorate one of the most famous instances of political theater in Chicago history, an event that foreshadowed the coming police violence. In an interview with The Chicago Tribune, Durica said: “It allows for an opportunity to interrogate those moments: how effective are these methods and techniques in terms of raising public awareness? It’s also a fairly accessible and animated way of approaching a very complicated narrative that still resonates within many communities throughout the city. I hope that this program can inspire us to address the more serious issues emerging from this story.”

§

Soon after the events of August 1968, Chicago Review (20.4/21.1) made its own “daring contribution to convention coverage,” in the words of poetry editor Iven Lourie. Arguing that the existing (and extensive) “reportage” offered “little that conveys the atmosphere and quality of the week’s events,” CR offered up the “raw transcript” of reel-to-reel recordings made by a PhD student and folklorist, Bruce Kaplan, “a fantastic tape made in Lincoln Park during the convention.” In a memoir that will soon be published in full, Lourie expands upon his brief introduction to the feature with further detail:

The Fantastic Issue…included a smattering of surrealistic pieces and a pièce de résistance which was a longish text edited from transcripts of a series of interviews from the Democratic Party Convention in 1968 in downtown Chicago. That was the infamous event that brought the Yippies to town to mock and harass Mayor Richard Daley and the party that would nominate Hubert Humphrey to run against Richard Nixon—at the height of the Vietnam War—and lose the election. The Yippies nominated a pig for the high office, and they refused to call off the demonstrations when Daley canceled all permits for demonstrating or camping in the downtown Chicago parks. This led to pitched battles in the streets, tear gas floating all through the downtown office district, the Loop, and battalions of Chicago policemen in riot gear making passes through the parks to clear them with tear gas, batons, and handcuffs when necessary to arrest resistors. The National Guard—platoons of young men around my age at the time carrying Army rifles—were bivouacked in Grant Park. It was a miracle that more people weren’t killed (there was one accidental death when someone was run over by a vehicle), but the injuries were legion…. I engaged my sometime roommate, Bruce Kaplan, who was a genius with a Uher reel-to-reel tape recorder, to walk around the park and do random interviews of participants. I did a few recordings myself, but the work was mostly Bruce’s. I knew Bruce from the Folklore Society at U. of C.—he was one of its leading lights. He helped plan and bring off the mid-winter U. of C. Folk Festival for a series of years in the 1960s, and this was my other extracurricular activity that got me a slice of education not available in the classroom.

Bruce was a Ph.D. student of Southeast Asian studies and Folklore, and he had great expertise in recording “field interviews” and simply a gift for getting people to loosen up and talk on tape. Bruce got interviews with people of wildly divergent views…. There were several dozen interviews, including tape of Black Panther Bobby Seale giving a speech in the park, and we paid a professional transcriber to type all of this out as a text. I then worked with Bruce to edit it down somewhat, and we published it in CR as our own version of Convention coverage, a collage of voices from the edge.

To mark the anniversary of the momentous events of 1968 in Chicago, we’re linking the entirety of that original documentary coverage here: Convention Coverage. The feature concluded with a poem, written on the spot by Burton Lieberman in Lincoln Park on Tuesday night, August 27: “We Serve and Protect.” Here’s a sample from the poem:

pigs! pigs! pigs!

motherfuckers—fascist pigs

cocksuckers pigs pigs pigs!

It’s a fascinating text—fantastic even; and fifty years on, the legacies and lessons of 68 seem more relevant than ever.

– Eric Powell, Editor

Notes:

[1] Richard Vinen, 1968: Radical Protest and its Enemies, (New York: HarperCollins, 2018), 111.

[2] Vinen, 112.

August 28, 2018

The Maids, by Jean Genet

Directed by Michael Conroy

June 22–July 21, 2018, The Artistic Home

Reviewed by Max Maller

Left to right: Hinkypunk as Solange, Brookelyn Hebert as Madame, and Patience Darling as Claire. Photograph by Joe Mazza, Brave Lux.

“Acts have esthetic and moral value only insofar as those who perform them are endowed with power.” In his first prison novel, Jean Genet, the narrator in Our Lady of the Flowers (Notre-Dame-des-Fleurs, 1943), off-handedly puts forward this theory of gesture as young Louis Coulafroy wanders unnoticed into the village chapel, where he profanes the altar and knocks over a ciborium. It is typical of Genet’s early style to be sententious in passing, but the notion that power transforms movement into actions of “esthetic and moral value” lays wide open the mechanism of his great play, recently at the Artistic Home in West Town, The Maids (Les bonnes, 1947), a one-act drama loosely inspired by the Papin sisters, who murdered their employer René Lancelin and her adult daughter at their home in 1933.

In Genet’s theater, as well as in the more documentary and diagnostic areas of his early prose writings, there is no disjunction of the aesthetic and the ethical for those in control of their destinies. What the masters do is beautiful because it’s what masters do. The rest of us primp and imitate, for better or worse. The symbolic gestures of priests imitate the first executant, Christ. Lovers morph into one another over time: “A male that fucks a male is a double male!” screams Darling Daintyfoot, the pimp in Our Lady. Danger, the creative threat of it, creeps into the frame wherever powerless, hounded people violate their born roles, either through blatant insurrections in manners or through shamelessly and covertly behaving like big shots. Claire, the one maid, trying on Madame’s red velvet gown from the closet, finds she looks better in it than her “flabby” boss ever did. Solange, her accomplice, speaks too heightened a language for a domestic in a French play. There is a tradition going back to Roman comedy that these breaks with appropriate class behavior will always be paid for in blood, to yips of applause, and nobility exonerated; Genet incurred scandal in his day by showing the maids’ crime while eliding their justice immanente. But we can’t imagine these unpunished moments of triumph lasting. And furthermore, Genet never lets us unsee what a maid in red velvet has always been in plays: an omen of social chaos. There are and always will be, as Solange says, “gestures reserved for Madame.” “The maids’ dilemma is that there is nothing they can do to Madame that would not confirm their identity as maids,” writes Leo Bersani, Genet’s best critic.[1] To muck around with Madame’s privileged gestures in secret—as we see the maids spend the better part of the play doing before their climax—is to expose, palpate, and in a bizarre way honor, life’s most fragile hierarchies.

This production, directed by Michael Conroy, stars two drag performers from Chicago as Claire and Solange. Very imperfect speakers, Patience Darling and Hinkypunk are stage actresses only to a point. They both, and Patience Darling especially, tend to overexaggerate the floweriness in Genet’s long speeches. (The parts that are written as spoken barbs aimed at one other’s throats fare better at their hands than the flashier ones.) But drag’s poetics of the overwrought lends a fruitful destabilizing effect to Conroy’s production.

Left to right: Patience Darling as Claire and Hinkypunk as Solange. Photograph by Joe Mazza, Brave Lux.

Acting is never just acting, though. Appearance is at a heightened register from the beginning. Patience Darling and Hinkypunk’s extraordinary makeup compounds and emboldens the eye until it dominates face and forehead. By virtue of casting drag queens in the first place, the drama of confinement to a specific gender plays out within the work’s pre-inscribed emphasis on class confinement, staging, in effect, drag’s rebellion against a society-wide theater of gender as allied to the maids’ struggle for reinscription and recognition at Madame’s house. Bold politics only excuse so much; cues do drop, and diction flutters; but we get electricity throughout, and whether these are great performances or no, they can’t easily be forgotten.

This production’s fixation on the visual and bodily is thanks in no small part to the suggestiveness of Zachery Wagner’s costume design. The back of Solange’s leather apron is in a harness shape, with harness fasteners. That’s not how maid’s uniforms work. It would usually be two gored panels in front and the same in the back, or a halter. Claire’s kinky buckling collar isn’t standard either. These are bondage outfits. The play as a whole is thick with bondage vibes, as when Solange pulls out a riding crop from behind Madame’s closet and twirls it over Claire’s hunched limbs on the line, “Take your place for the ball.” There is consent, we feel—it’s vicious, but it’s a game. Then the game goes too far.

Cooped up in the mistress of the house’s bedroom all day long while she’s out, Claire and Solange begin the play, not as Claire and Solange, but as “Madame” and “Claire.” In character, so to speak, they apply Madame’s perfume, rough up her Louis XV chairs, take pins from her vanity, and so on, purring with delight and occasionally slapping one another silly. What’s immediately clear about this sadistic round of recess is that our maids are horribly depressed, vengeful, and up to their noses in reckless fantasy lives. They dub their routine a “ceremony”; within it, no meaningful distinction obtains between disciplinary thrashings in character—that is, as Claire (“Madame”) tyrannizing over Solange (“Claire”), kicking and slapping her to pieces—and real ones, so long as Solange’s blood gets scrubbed off the steps before Madame, the actual Madame, played by Brookelyn Herbert, returns. To end the ceremony, to start the world over again on fairer terms, or simply to get out of this damn apartment once and for all, someone is going to have to die. That somebody is Madame.

But in the play’s atmosphere of dreadful imposture, Claire’s idea of murdering Madame with a drugged tea feels like something in a dream, even as it starts to happen. A degree of mistrust on the viewer’s part seems sane to me. What’s plotted, what’s carried through, and what’s simply a case of cabin fever and patent leather talking, is very much left up in the air. Are we to take Claire at her word that it was she, Claire, who fingered Madame’s beau (a “Monsieur,” who does not appear) to the police for petty theft? Does Madame die? Does Claire? Is Solange arrested? We need an outside perspective, a second opinion. With no Fortinbras to show up and inventory the Act Five carnage at Elsinore with a level head, no policeman to scratch his stomach in the doorway and say “What in the hell happened here?”, we can never know for sure what went down or was about to go down at Madame’s place. Additionally, there’s a Mario the milkman. Here, Genet’s arch faith in the blur, his refined taste for sham, is at its most troublesome. Jean-Paul Sartre, in his 1952 introduction to Les bonnes, describes the “whirligigs of being and appearance” in Genet’s prison books and early theater as a vast array of sophistic circles.[2] Okay, Epimenides. So either this milkman has gotten in through the window and raped both Claire and Solange, or else maybe, in a different telling that follows, he has impregnated Solange with an unborn fetus that she and Claire will somehow both be carrying and delivering in tandem—or perhaps, as feels more than likely, there isn’t any milkman at all, and we’ve gone a little crazy in here, what with the heat and perfumed air.

Director Michael Conroy never forces the issue one way or the other on these perplexities, but the late entrance of Madame at least compels a crude accounting for some of the incrimination and doom that the play claustrophobically bandies for its first hour prior to her arrival. She is magnificently bossy and fatuous. She wants to know who used her perfume: it was Claire. That clarity is so refreshing after our hieratic season in hell that, even if it’s fleeting clarity, we’ll take it. It’s fascinating to compare Herbert’s signature gestures with Patience Darling’s ventriloquism during the ceremony. One suddenly realizes just how much you have to love someone and study them in order to do a convincing impression, how much psychic real estate they will necessarily have to colonize before their moves can come out of your body, their voice from your mouth. But if some combination of envy and misfortune ever made you want to become that person, you would never be able to, and that might make you want to kill them.

This is a queasy play. Not the least troubling of its effects is the sense of a bedrock familiarity with human conduct, as seen through the cracked glass of Genet’s lifelong experiment in deformed life. The show ends, as it started, mysteriously, neck-deep in the rubble of Solange’s towering threnody of a final monologue. In a deposition to the invisible police, Hinkypunk calls up unbelievable power, which we have seen only the surface of until now, for almost ten whole minutes of speech. A shocking finish, out of nowhere it blazes on the wreckage of three ruined lives, is amazing, and signifies nothing.

[1] Leo Bersani, Homos (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1996), 173.

[2] Jean-Paul Sartre, “Introduction,” The Maids and Deathwatch: Two Plays, by Jean Genet, trans. Bernard Frechtman (New York, NY: Grove Press, 1994), 1.

August 2018.

Waiting For Godot, by Samuel Beckett

Druid Theatre Company

May 23–June 3, 2018, Chicago Shakespeare Theater

Reviewed by Max Maller

Marty Rea as Vladimir and Aaron Monaghan as Estragon in Druid theatre company’s Waiting for Godot, directed by Garry Hynes, presented as part of WorldStage at Chicago Shakespeare for a limited engagement in the Courtyard Theater, May 23–June 3, 2018. Photo by Matthew Thompson.

Step right up, folks. See no-show Godot and the two forgetful farts. Get a load of Mr. Moneybags with his valet on a big leash. Liked it the first time? Stick around for the second act and catch the entire blooming, buzzing, epistemological potato sack race to oblivion once more from the top, only slower this time, with feeling, but not in the toes. I forgot the kid! There’s a kid in it. Isn’t he cute? But he won’t remember being there and neither will anybody, if he was even there to begin with. And so too will our cinders get flushed headfirst down the proverbial Abbey Theater jakes during a matinee showing of At the Hawk’s Well, as described in section six. Nihilism! Modernism! L’chaim! ǫᴜᴀǫᴜᴀǫᴜᴀ. Excuse me. Rinse and repeat.