Chicago Review, the Beats, and Big Table: 60 Years On

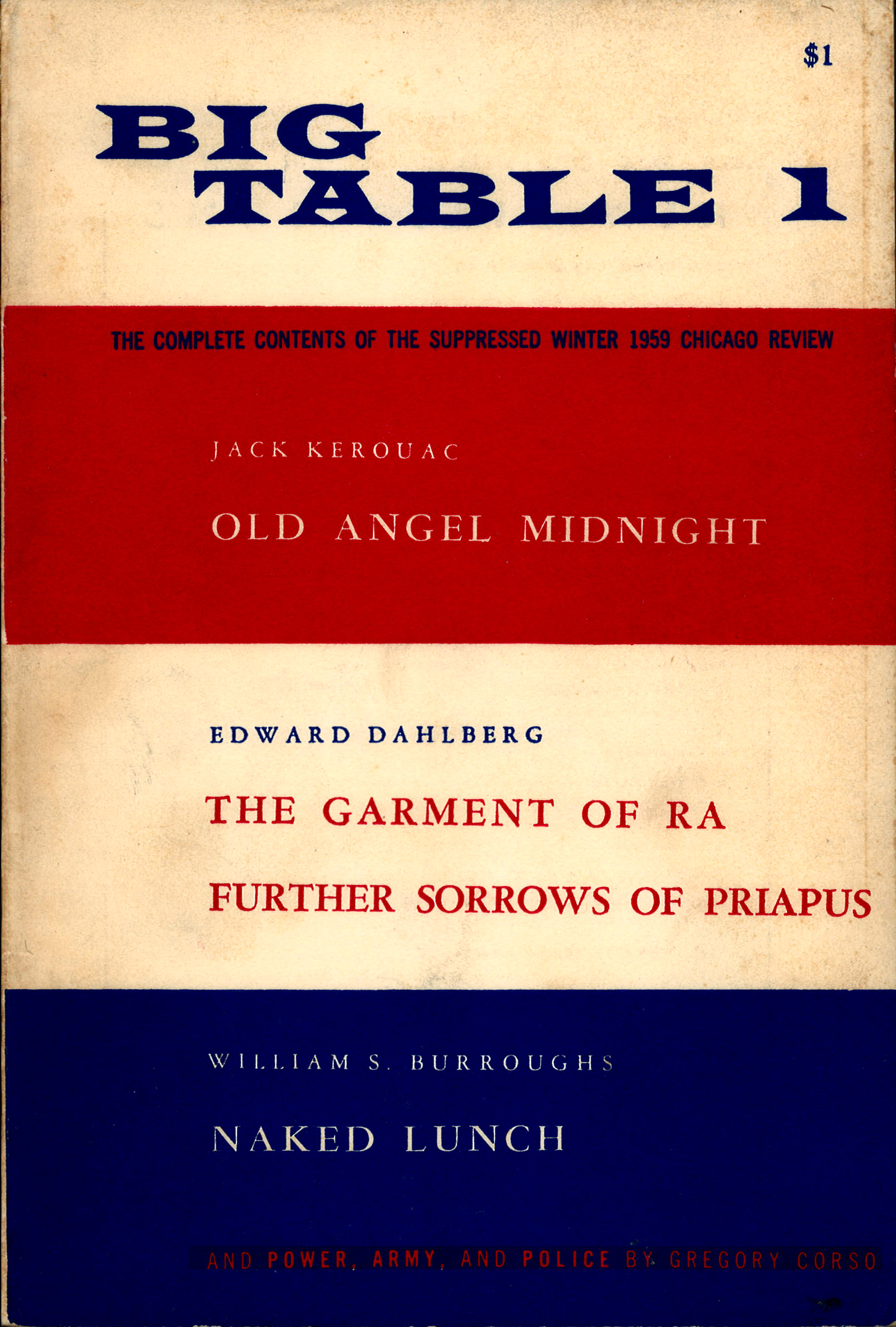

Cover of Big Table 1, 1959.Preface

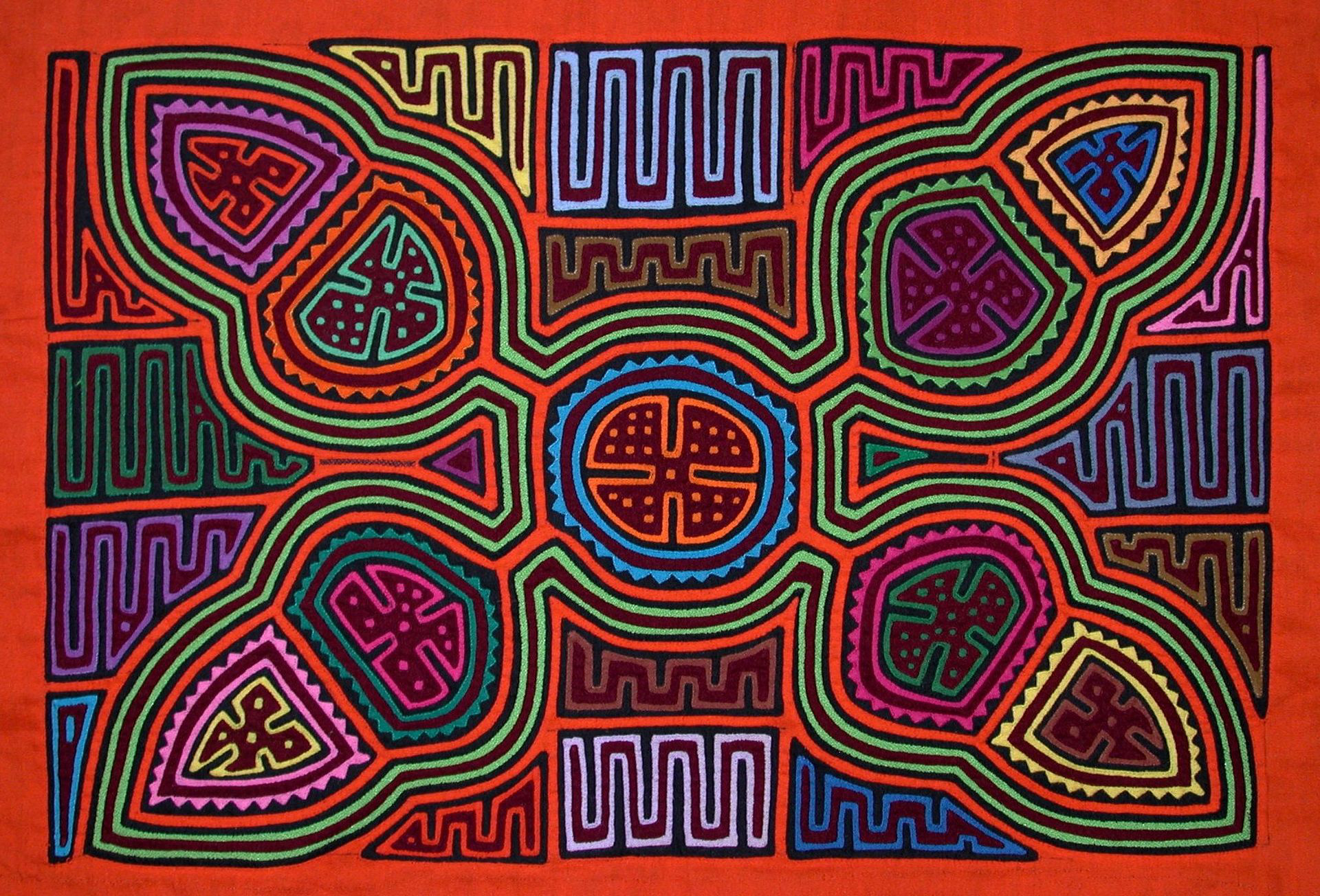

This year marks sixty years since the publication of the first issue of Big Table, the journal started by Irving Rosenthal, Paul Carroll, and other staff members of Chicago Review after the University of Chicago suppressed the Winter 1959 issue of CR. We gather a wide array of materials here to commemorate the anniversary, and to look back to an important episode in American literary history. The Big Table story, and CR’s history leading up to it, is told in detail in former Editor Eirik Steinhoff’s essay “The Making of Chicago Review: The Meteoric Years (1946–1958)“; this was published in CR’s sixtieth anniversary issue, and appears in an expanded, revised form here in this feature. Rosenthal and Carroll began publishing the Beats in 1958; some of the correspondence between the editors and Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, and William S. Burroughs is included in this feature. Excerpts from Burroughs’s Naked Lunch appeared in two issues in 1958 (12.1 and 12.3); a journalist for the Chicago Daily News responded with an article titled “Filthy Writing on the Midway,” in which he called on the trustees, no less, of the university to “take a long hard look at what is being circulated” under their sponsorship. They did so, and soon Rosenthal was told by the Dean of the Humanities Division that the next issue had to be “completely innocuous.” Rosenthal called a staff meeting, the notes from which are included in this feature, in which two options were considered: refusing to comply with the strictures, or electing “a new editor of the Review who could publish in good conscience a next issue which would be acceptable to the University.” Understanding the risk that was posed to the future existence of CR in pursuing the first option, the second route was chosen by vote. Hyung Woong Pak was elected the new editor, and went on to edit several excellent issues. The rest of the editors resigned, taking with them the manuscripts of work by Burroughs, Kerouac, and Edward Dahlberg that were to appear in the next issue of CR, with which they started Big Table. It was a principled editorial stand against censorship, and a shameful episode in the history of the administration of the University of Chicago, which has now made a brand out of championing “free expression.” The affair sparked off internal controversy, including an investigation by a Special Committee of the Student Government (selections of the report are included here), and the Chicago Maroon, the University’s student newspaper, covered the matter in detail. But it also became a matter of national debate—a number of clippings are included below—and was a part of a larger process of the triumph of Beat literature over what were perhaps the last attempts to suppress literary work in the US through the charge of “obscenity.” After suppression by the University, Big Table was confiscated by the US Post Office. The ACLU took up the case for the publication and won, Joel J. Sprayregen, counsel for the ACLU, claiming that “this is one of the most important censorship decisions” since James Joyce’s Ulysses. Allen Ginsberg, Peter Orlovsky, and Gregory Corso gave a poetry reading in Chicago as a fundraiser to help establish Big Table (the press release is included here). A snide article covered the event in Time magazine: “With the crashing madness of a Marx Brothers scene run in reverse, the Beatniks read their poetry, made their pitch for money for a new Beatnik magazine, The Big Table, and then stalked out.” This chauvinism from the literary establishment elicited a classic Beat response from the poets:Your account of our incarnation in Chicago was cheap kicks for you who have sold your pens for Money and have no Fate left but idiot mockery of the Muse that must work in poverty in an America already doomed by materialism. You suppressed knowledge that the Chicago Review’s winter issue was censored by the University of Chicago; that the editors had resigned to publish the material under the name Big Table; that we offered our bodies and Poetry to raise money to help publish the magazine, and left Chicago in the penury in which we had come. […] You are an instrument of the Devil and crucify America with your lies; you are the war-creating Whore of Babylon and would be damned were you not mercifully destined to be swallowed by Oblivion with all created things.

The first issue of Big Table was a success, and Paul Carroll would go on to edit four more numbers, and publish several books under the imprint of Big Table Books. Rosenthal took the opportunity of the publication to tell his version of the story in an “Editorial,” which we include here. Not mincing words, Rosenthal refers to the administration’s actions as blatant censorship, writing that Lawrence Kimpton, the Chancellor at the time, “does not want free expression at the University of Chicago; he wants money.” The episode left its mark on former editors, and has been passed down as a defining moment in the history of CR. As we approach the journal’s seventy-fifth anniversary in 2021, we’ve been collecting memoirs from former editors and staff members in an experiment in collective self-memorialization and self-historicization. To round out the feature, three memoirs are published here: one from Barbara Goldowsky, née Pitschel, who joined the staff under Rosenthal, resigning as Managing Editor; one from Edward Morin, who joined the staff at the same time as Rosenthal, and went on to serve in several editorial positions, moving on just before the Big Table fracas; and one from former Editor Peter Michelson, who joined the staff under Pak’s editorship just after the events of 1959. Together, the three memoirs recount the period leading up to the suppression ordeal, the event itself, and the aftermath. Happily, the period of University oversight of CR passed, as did the period of attempts to suppress the Beats and other writers for obscenity. What has lived on is the writing itself, a testament, among other things, to editorial insight and courage.– The Editors

Read the full feature here.Fiction Staff’s December Feature

Bruce McAllister’s “Why My Mother Killed Herself” seems to promise explanations but then refuses to give them. Or, if it does, they take the form of an elliptical trace. The movements of the story suggest that a space might be found at the center of the three apparently disparate episodes that make the narrator’s mother cry—an absent event connecting the death of a pet dog, a book of Chinese poems, and a remembered story her father used to tell. The story’s brevity, barely skating along the edges of narrative, offers sketches of disparate but resonant objects—like the lovely, odd, potentially found poems—which allow the connections between them to hover at the edges of what can be seen or felt. Birds fly but do not sing in flight.– The Fiction Staff Bruce McAllister Why My Mother Killed Herself There were three things that made her eyes, which were not like mine at all, tear up. The first was animals—animals too weak to live. When our dog died, a little bull mix that whined too much, I didn’t know for days that it had. I was a teenager. When I found her in the backyard, on the dead lawn, by the fence, she could barely tell me. “She’s always been sickly” was all she could manage. I wanted to know why she was really crying. It was terrible not knowing. The second was poems in Chinese—a little book her mother had given her in Morelos before I was born—which she really loved.Clouds float into a great expanse. Birds fly but do not sing in flight. How lonely are the travelers. Even the sun shines cold and white

And this:She rides a red leopard, striped lynxes attending, Her chariot arrayed with banners of cassia and magnolia, Her cloak made of orchids and her girdle of azalea, Calling sweet flowers for those dear to her heart.

The third was a story—one she told to anyone in the neighborhood who would listen. It was one her father used to tell before he left them—about a boy with a limp who tried to help a wounded man in a saloon gunfight in Juarez a hundred years ago, and how he was killed by a heartless man for trying. “Just for trying,” she would say, unable to stop crying.Poetry Staff’s November Feature

This long poem by Lotte L. S. gathers fractured perspectives in a persistent and persisting voice: forthright yet observant, not impervious to beauty, but keeping one eye to the deadening structures of capital and the state. The body at the centre of these perspectives is a little anonymous, a little fungible, enlivened by moments of sexuality and sensuousness that stretch beyond their immediate present. When she hypothesizes that “time is just perspective, and / perspective: time,” perspective emerges by turns as a situated limitation and a site of possibility. Annual and diurnal rhythms overlap, appear in fragments, feel disorienting or eternal; the speaker is suddenly in a narrative and just as suddenly outside it. And she is spoken through by other poets who might share those perspectives and experiences. “Imitating crown shyness,” her life is apart from others yet shaped by them exactly, inhabiting the spaces they have vacated or left behind. – The Editors and the Poetry Staff Lotte L.S. Twelve Days of 21st Century Rain A voice rang out from the boiler in visceral encounter: “You must change your life.” The hibiscus moved in the breeze, everything else staying still. Well: the seagulls, the seagulls. Carbon monoxide had already claimed the last inhabitant — as if to misread sleep like to think of myself high up at the window imitating crown shyness continually changing faulty light bulbs at the ends of summer hesitating to thrust myself into others’ lives, other lives. A life, all £430 worth of it. Dangerous of course to draw parallels: tried the detectors, tried the weekly whole-building alarms, tried to imagine I could change my life — her dancing beneath the pines, told me: to love without doubt is to fuck without desire, and yet the nectarines are still ripe and juicy on the table at this time of year but I want them hard as can be, actualised at the ends of a midnight-blue corset dream — hands enough to touch yourself and watch the starlings murmur, a whole host of fish unionising at the same time every year to swim a full circle and disappear, wondering if time is just perspective, and perspective: time. It touched me where it hurt, but the hurting felt good — seagulls watching from each rooftop, St George’s Cross flags razed across every allotment plot long road of curtains rippled open, crystallise my senses alone with a boiler that doesn’t emit a smell or sound or sight and all the windows are open — miniature ballet dancers twirling off the sill in small succession someone screaming, “I’m gonna fucking kill you you motherfucking son of a bitch” cries streaming over from the dark-bright street below, weekly Tuesday fireworks jacked-up and disseminating in rounds from the beach. In the almost darkness we cannot delegate “our” desire, seagull shit dripping down the windows in hot, thick tangles of a flat last inhabited, and I would have to say “OK, thanks. I didn’t know.” Why is this night different from all the others? The emphasis to fall on the asking, the making of an unchanged life awake until sunrise — avoiding the surprise of sleep gave me dreams: trees lining boulevards in the south of France you absentmindedly on your knees in the corner tipping something softly down the back of your throat. Do you know it? I tried to laugh and understand the pieces of human movement, one glance capturing a shape that emerged from them all: the fascist compost of the allotments, green was the forest drenched with shadows of my own lack — I decided I’d rather throw every broccoli head in the bin. And my own: a tenant to evict, landlord a penis to guillotine, police sirens ricocheting across the curtains unduly feminised in their flutterings, pink lilies bursting from the vase on the floor telling me: “I want to live deliberately” — “I want to live alive” headphones on means I can’t hear them coming down the boulevard coming down the high street the road I inhabit that leads so clearly to the sea — striding their guillotined dicks down the deserted streets. A woman was arrested the other morning, I saw it from the window: cops cuffing her to the car, miniature ballet dancers spinning from the windowsill gliding through the soft lace of the air to pinch cop tyres flat with their tightly pricked slippers. He literally wrote a worldview wherein she “went” out the window of his thirty-fourth-floor New York apartment in a blue bikini and a judge signed off on it. Awareness, or blossom: an archived commodity in which perspective is the removed corset often police ourselves to take off our clothes — but what’s another way to look at this? What else could you have asked? If you don’t recognise me among the treed-up, jacked-up roads the logical supposition of boulevards I have never been it is because I took off all my clothes in my most confrontational means I can’t hear them edgelit and hooting in the trees a politicised people suddenly and casually wondering if you were going to take your socks off before you came. These days I am trying hard not to come so consistently — instead asking my mother, “how are you feeling today?” wondering if I’ll ever see her dance beneath the pines, fantasise about suffocating my landlord with deliberate marmite: a whole feast of mugwort on the bedside table; gave me dreams of killing children, told me to dare imagining it’s not a thing you can touch Notes: ‘Dangerous / of course / to draw parallels’ is lifted from ‘Sunset, December, 1993’ by Adrienne Rich […Yet more dangerous to write / as if there were a steady course, we and our poems / protected: the individual life, protected’] // ‘and all the windows are open’ is reworked from the final line of Gloria Dawson’s poem ‘What Dreaming Makes.’ // ‘We cannot delegate “our” desire’ is reworked from Communiqué 7 by the Angry Brigade // ‘green was the forest drenched with shadows’ is lifted from The Spring Flowers Own by Etel Adnan. // ‘the soft lace of the air’ is reworked from ‘Poem for Haruko’ by June Jordan. // Carl Andre claimed that the artist Ana Mendieta “went out the window” of his thirty-fourth-floor apartment, wearing a blue bikini, early on the morning of September 8, 1985. He was accused and acquitted for her death, choosing a judge over a jury. “She made me change her light bulbs. She was afraid of heights. She would never go near the window,” Carolee Schneeman later said. // ‘Awareness, or blossom:’ is reworked from ‘There’s an affinity between awareness and blossom.’ in ‘Hello, the Roses’ by Mei-Mei Berssenbrugge. // ‘perspective is the removed corset’ is lifted from ‘After Vuillard’ by Sarah Maclay, first shared at Community of Writers 2019. // ‘to dare imagining’ is lifted from To Dare Imagining: Rojava Revolution, edited by Dilar Dirik, David Levi Strauss, Michael Taussig and Peter Lamborn Wilson.Fiction Staff’s November Feature

In Ruthvika Rao’s “Thirteenth Day,” the worst has already happened: a father is dead, and his children must make sense not only of their loss but of the thirteen-day mourning ritual that’s been thrust upon them. Over the course of the story, the familiar comforts marshaled against the grief—food, family, scripture—begin to overwhelm the young narrator. Her home swells with distant relations who suck the air, click their tongues, and belch; the shoes they pile at the door give off a “smell of old leather and musty feet”; a looped recording of the Bhagavad Gita etches itself into her skull. Early on, as the father’s corpse is prepared for cremation, a group is sent out to buy air fresheners “to bury the odor of the dead under the plastic, manufactured smells of jasmine and lily.” Shared grief, Rao reminds us, can take its toll on our senses and also on our relations. Family members become strange: the narrator’s brother appears looking like “a stranger showed up at our house wearing my brother’s eyes,” and the mysterious relative Amruth thaatha, who nobody seems to remember, is fatefully welcomed into the fold. Amruth thaatha steps in as the children’s caretaker, tenderly untangling the narrator’s hair and preparing her for each phase of the ritual. He is warm and kind, and she grows fond of him, making the emotional unfolding at the story’s sudden end that much more nuanced. With “Thirteenth Day,” Rao gives us a compelling exploration of the sensorial and relational complexities produced by mourning rituals, community caregiving, and trusting others. – The Fiction Staff Ruthvika Rao Thirteenth Day First Day They take Arjun. He is required, as the only son, to perform the holy duty of setting my father on fire. I don’t know what he thought then, what fears swirled in his mind. I stayed home with my mother and the other female relatives while Arjun walked out the door, stepping over the embers of his crumbling childhood. Amruth thaatha goes with Arjun. This calms me. Thaatha was the type of person you immediately trust, in whose hands you feel safe, warm. He holds Arjun’s hand and pats the top of his head. Then they leave with our father. We called him thaatha, my brother and I, even though he was not our grandfather—this previously unknown relation, who showed up at our door on the eve of our father’s death. My brother and I were sitting at the feet of our departed father in the middle of our living room. He is shrouded in white from head to toe, and the mourners spread around us like the tracks of a magnetic field. The furniture had been pushed away to make room for the grievers and the grieved. There was a gauze bow on my father’s head. The cotton gauze ran around his chin and ended at the top, like a cruel present. More gauze was packed into his nostrils. This was highly discomforting for me, and I suppressed an intense desire to crawl over his torso and pluck the gauze padding out. It looked uncomfortable. I wanted him to not be uncomfortable. I was dimly aware of the odor seeping out of him, despite the room-freshener and the rose petals. It is a scent that imprints itself under the surface of your brain and condemns you to carry the memory of it for the rest of your life. When I first met thaatha, I could not see his face. This was because I had misplaced my glasses and was afraid to ask my mother to find them, like I normally did. She was sitting in the corner of the room, her sari and hair disheveled and her vermillion bottu a smudge. Her dark eyes were purple from a day of crying. New wrinkles had shown up over the course of the day, and deep lines had sewn themselves into her caramel skin. In her current state, I did not want to ask her to find my glasses. I was glad that I was seated close enough to our father to be able to see his face. A few feet away and all I would have seen would be a blurred vision of snow-white gauze hiding a chestnut-brown face. Arjun sat in the far corner, nearly burrowed underneath the television set. The mourners patted his head and hugged me. Perhaps because I was a girl, I was given the privileged spot at father’s feet and allowed to weep at will. I was exhausted from crying. My eyes struggled to stay open and my head drooped into my chin. A relative would say poor little girl and suggest moving me into the bedroom to sleep. In that moment, I would force my lids apart and prove to everyone that I was indeed quite awake. I clung onto my father’s motionless feet and refused to move. It was nearly time for him to go. I wanted to stay until the very end. They came in the morning, the breast-beating women and the stoic men. They came in droves, raising dust that we could not see. My mother has no siblings or parents who are still alive. So a group of helpers from my father’s side took over the house. They sent people to buy more air fresheners from the kirana shops, to bury the odor of the dead under the plastic, manufactured smells of jasmine and lily. They passed around steel glasses of water to wipe the salt from the mourners’ faces. There was an eerie silence in the kitchen. The stove was cold, and no one went inside. A tape recorder played and replayed the Bhagavad Gita, as narrated by Ghantasaala. After ten hours, the words of the holy book were etched in my skull. Those who take birth cannot escape death, and those who die cannot escape birth. The dulcet tone of Ghantasaala would both calm me and drown me in inexplicable sorrow for the rest of my life. The leader of the helpers—the tape-replayers, the air-fresheners, and the water-glass-passers—was Amruth thaatha. His desperately yellowed clothes stood out amongst all others who dressed in crisp white cotton. I only saw his face when he sat by me holding the water glass and told me to wipe my face. I was unsure of what that instruction meant and stared at him. He had kind eyes, like wrinkled almonds. I shook my head. He dipped four fingertips in the glass and wiped my salt-caked cheeks. I felt his warm, callused fingers on my skin as he dipped them into the glass and got my other cheek. I had only then noticed that my cracked skin was singeing underneath the salt tracks my tears made, in the breaks in my cheeks and the torn corners of my lips. I continued to observe Amruth thaatha as he repeated the instructions to my brother. When Arjun came back, he was wet. He had taken a bath in the river that ran along the cremation ground. There was sand between his toes, and I imagine him walking along the riverbed after his dip in the cold water, shivering while his bare feet pick up the sand. He was also completely bald now, his dark locks offered to no god. I knew it was my brother, but it felt like a stranger showed up at our house wearing my brother’s eyes. He wasn’t crying. He looked like the dutiful son, and with his wet clothes and his bald head, he looked honored. He was no longer a child but a man then, unafraid of what life was to bring him in the future. Amruth thaatha held him close, patted his shoulder, and picked a stray hair from his face. After the men return from the cremation grounds, the kitchen swung back to life, and the business of feeding the mourners took hold of everyone’s minds. Everyone except my mother. She did nothing. She had showered and, as custom dictated, washed her hair, like I had and like everyone in the house had. She had not bothered to dry her hair. It was in a loose braid that made a wet, snaking patch on the front of her sari. I did not recognize her white sari. It was produced by a concerned relative who had taken it upon themselves to welcome her into the fold of widowhood. She sat with her back to the window. A path of sunlight filtered through and warmed her hair as Arjun lay in her lap. They were both suspended in stupor, in private mourning without me. I watched them and felt an alienation that only the youngest child of the family was capable of feeling. At my father’s side, they cooked, they ate. The men drank, the women gossiped, while we sat by ourselves near my father’s newly constructed altar. A blown-up passport photo of my father, without his usual dimpled smile, had been framed and garlanded with copper marigolds. A vase of rice lay before him, with two standing sticks of incense burning at its center. A mud lamp burned a low flame. The sight of the brown whiskey bottles and the raucous laughter drove my brother and me to the storeroom, where we sat among the jute sacks bulging with rice. Amruth thaatha found us. “Come outside,” he said. “It isn’t hot today, you should sit in the sun.” The heat warmed our heads as we sat on the stone steps outside the house. A sea of footwear lay before us, whose various owners had left them haphazardly before entering the house, and the smell of old leather and musty feet was not altogether unfriendly. The street was calm. A scooter passed by the house, and a dog wagged its tail expectantly toward the smell of cooking food. Amruth thaatha produced a pocket comb and worked through the knots in my wiry hair. He told us stories about the king Krishnadevaraya’s conquests and about his clever court jester, Tenali Rama. I still couldn’t see well, but I travelled far, far away. Third Day They immersed his bones and ashes today, Arjun told me. I was not allowed to see them, but Arjun went again to the river. They warned us not to touch outsiders until the thirteenth day. We were kept from school. It had swept over me when his thatched bed was lifted off the ground, a feeling like relief, when the marigolds and rose petals spilled out, like a logical end, expected. The relief dripped away with every reminder of my father’s non-existence—there was a steady drip, drip, drip. His slippers by the bathroom. The dozen starched shirts delivered by the dhobi’s son the day after, and the smell of his leather wallet that Amruth thaatha counted money out of, as the pimpled boy waited awkwardly. The dresser in my parent’s bedroom, the only room the relatives had not overrun, on which his watch glinted against the striped gray Decolam. His comb, his talcum powder, his coconut oil, jumbled together with my mother’s broken bangles, dried flowers and plastic packets of bindis she would never again use. I felt his presence everywhere, and a hole dug its way into my heart. It grew bigger every time I rounded a corner and saw his stacks of books and every time I heard the iron gate creaking open to let another relative leave. The pile of abandoned footwear outside the door shrank by the hour. Tradition forbade them from saying goodbye to the family members in whose house death had occurred, and they vanished gracefully into the cemented street one after the other. The interlude was over. Life resumed. The newspaper boy started throwing us our newspaper, and the milk boy rang the doorbell after dropping off the leaky half-liter plastic packets of buffalo milk. My brother and I found ways to occupy ourselves without entertaining ourselves. Everyone left. That is, everyone except Amruth thaatha. He cooked for us, cleaned after us, bought the vegetables, weighed the rice and the dal, bargained with the green leaf seller in the foggy morning with a towel wrapped around his head like a scarf, and barked at the careless garbage boy to not leave trails of wet waste in the courtyard. He made cars out of clay for us and fed us rice while narrating stories in an arresting baritone, of kingdoms many, many moons away. He slept on a canvas cot in the yard with a large cane next to him, to scare off robbers, he explained. He was up before us and slept after tucking us into bed. Our mother, on the other hand, relinquished all household duties and confined herself to the bedroom for the entire day, asleep on the bed in a white mound, a figure that sometimes did not move for days at a time. Thaatha left some meals at her door, a plastic water bottle, a steel glass filled to the brim with salted buttermilk or lime sharbath. The only time I saw her outside her room was in the morning after her bath, when she walked into the living room and lit the oil lamp in front of the framed passport photo. She removed the dried garland and replaced it with a new one, refilled the sesame oil in the mud lamp, changed the cotton wick, and lit it with a wooden matchstick. She briefly held her palms together and shut her eyes, and for a moment, she was transported into a world where I imagined she spoke to my father alone. Stolen conversations like the ones they used to have when he was alive. The image of her standing there would stay with me through to adulthood; the diaphanous, cloudy white figure standing against the filtered light of the sesame lamp. I did not wonder at the time why Amruth thaatha was still with us. Thaatha brings me a plate of sambar rice with a generous helping of ghee. He mixes these with his hands and sits me down on the cement verandah. One meal a day, we sat together on the veranda and he narrated fantastical stories. “I owned so much land in my day,” he said, “that I had to ride on my horse for an hour to cross it.” “Where is it now?” I ask. “The horse?” “The land.” “Long gone,” he said. “Why?” “Some bad habit or the other in the old days.” “What habits, thaatha?” “What use is talking of it now,” he said and refused to answer this line of questioning. He smiled and nodded until I exhaust all my questions, then distracted me with tales of talking monkeys and sly crocodiles until there were only remnants of my yogurt rice left on his fingertips. Eleventh Day We clean the house. Amruth thaatha pulls out all the sheets from my parents’ room and dumps them in the yard. He tells the dhobi to take them and to keep them. Don’t bring them back into the house, he warns. He sweeps the yard with a reed broom. The yard is paved with Shahabad stone and littered with dried leaves from the neem tree. He gathers them up and lifts them into a green plastic bucket. They crinkle under the broom and thaatha’s knuckles bleed from accidentally scraping the stone. He empties the bucket behind the house and sets fire to the leaves. I follow him around, watching every move. The acrid smell of burning leaves makes my eyes water. He refills the bucket with water and carries it back into the yard, then dips a small mug into the water and sprays the mug-water onto the ground in a great arc. The droplets slap the stone and steam rises. The day had been hot. The rhythmic spraying, the fragrance of wet stone and dry earth settles into my nostrils. He goes back inside and sweeps, mops, and dusts the numerous crevices in the house with a sprout of bushy yellow reed, which he has tied to a tall bamboo stick. He holds it in his right hand and reaches up to the ventilators, while covering his nose with his yellowing upper cloth to avoid breathing in the decades-old dust. He washes all the linens and dries them on a line behind the house. The fluorescent clothespins are interspersed with the flowery bedsheets my mother had bought at the beginning of her marriage. He calls the catering contractor and selects meals for the thirteenth day: two rice items, two veg curries, two non-veg curries, two buckets of curd, ten blocks of Scoops-brand vanilla ice cream, and five liters milk for masala chai afterwards. A large canopy for the yard, he says, with blue and red stripes. Don’t forget the matching maroon carpets. He bargains with the flower vendor: twenty yards of marigold garlands, and throw in some loose flowers. He stacks extra LPG cylinders in the kitchen; a neat row of ferrous capsules stands against the grease-scrubbed wall. My mother hands him the keys to the beeruva. She does not want to get up every time and fetch money for the arrangements that thaatha makes. The keys hang by the waistband of thaatha’s dhoti. He opens the beeruva when he needs to, counts out the money without disturbing the violent colors of mother’s silk saris. He pays the caterer, the plastic chair renter, the canopy and carpet renter, the milk-boy and the paper-boy. Thirteenth Day The thirteenth and final day of mourning is for feasting and celebration. The caterer arrives. The sun hits the red and blue striped canopy unspooling in the yard, and a few stray beggars settle in neat rows outside the gates. Arjun runs with the children of our relatives who have showed up again. Thaatha has picked out a bright yellow shirt for him to wear, with navy long pants. His head has acquired a dark shadow and no longer reflects the sun. Thaatha dressed me in a red silk langa and a green blouse. I had grown a few inches since the last time I wore the langa, and it stopped above my ankles now, instead of brushing the tips of my toes like it was supposed to. It had a folded pleat sewn in, an extra length of fabric discreetly sewn underneath in anticipation of my frequent growth spurts, a forethought on my mother’s part in order to make my clothes last longer. Amruth thaatha stood me up on the cement platform in the yard and attacks the pleat with a safety pin. His eyes were not great, he misses every so often and made pinholes in the silk. I stood watching the blue-and-red-striped canopy unfold and the stale maroon carpets unroll. Thaatha plucked around my skirt, releasing the seams of the pleat. The skirt was too long afterwards, and it swept the floor behind me as I walk. The gold brocade border refracted light when I lifted it off the ground to race my brother. The carpets cover the entire yard. They smell stale, like they had been left overnight with cooked rice and incense. Today is a day of remembering the departed and cooking their favorite dishes, thaatha tells us. My father’s favorites were fried masala potatoes, lentil stew, and bagara rice, I tell him. The caterer cooks these according to thaatha’s specifications. My mother sits in the hall, and she is drab and colorless in her white sari. It was strange to see her outside her room. She is surrounded by relatives in colorful saris, and they stand sucking the air around her, clicking their tongues. The house swelled with guests. People ate, belched, drank, and the house filled with their laughter. They prayed at my father’s passport photo. They pinched my cheeks and complimented my skirt. Thaatha nudged me with a finger and reminded me to say namaste, so I smiled and brought my palms together and said namaste. Evening falls, and I’m by myself in the yard. I’m playing with pebbles that I had collected in the yard, and I was throwing them at the neem tree, three misses. I did not change out of my silk skirt, and there were still many relatives in the house. I would be back in school tomorrow, an end to the sanctioned isolation. My father walked me to school every day, and I was not sure how I felt about going without him. Perhaps it would feel like showing up without an arm or a foot. I see thaatha walk out of the door and toward the gate with a large cotton bundle under his arm. He spots me at the tree and comes over. He runs a hand through my hair. “Your hair knots fast. I combed it only a few hours ago.” He smiles. I continue throwing pebbles at the tree. “Look what I found,” he says, producing an object in his palm. My glasses. I grab them out of his hand, greedily put them on, and let out a satisfactory groan. I could see the lines in the leaves, the grooves in the tree, the stripes in the canopy, and the clouds spelled out in the sky. I also see thaatha’s face smiling down at me. He is older than I thought. The lines on his face are deep. Gray floated in his eyes. “Thank you,” I say. I’m grinning so hard, my cheeks hurt. I notice that thaatha is no longer standing behind me. There is a singular scream from the house. The sun was setting and the crows that were feasting on my father’s thirteenth-day rice cakes fly away. More startled shouts and raised voices. Whispers. My mother’s bedroom is crowded. The sea of legs becomes thicker as I navigate towards the epicenter. I push through the stubborn ankles and nudge reluctant elbows. A firm hand pulls me and holds me in place. I squirm and wriggle out of the grip with violent force My shoulder hurts. I can feel the fingerprints burning in place. It is all gone, they say. The beeruva is empty. The wedding jewelry, the silver, the cash, all of it. It is all gone. The poor widow, they mutter around me. Arjun holds my hand. We hold our breath. “Did either of you see Amruth thaatha?” they ask. “No,” we chorus back.Poetry Staff’s October Feature

These poems by Aleš Šteger, in Brian Henry’s translation, come from a longer sequence, in which Šteger manifests our inattention to language by calmly and deliberately unpacking the ontology of ordinary words. For Šteger, different words might have different ontologies, and he attends to the particular ways such words are situated within linguistic routines and commonplaces that here expand to produce a shared relation to history and a picture of social life. Ontology becomes poetry, and poetry is figured as origami: a kind of manual labour abetted by the hand of time and the things time makes unimaginable or mysterious. “The word folds” represents an arbitrary beginning, a history so imprecise it cannot be distinguished from legend and myth, except that what it singles out may be at once general and personal. To say “Once, there were…” is human, the work of an indifferent memory as well as an indifferent language. But the word near documents not only the desire for language to meet with the world, but the feeling of intimacy that lingers in other people’s words, including Šteger’s own. – The Editors and the Poetry Staff Aleš Šteger Translated by Brian Henry The word near The word NEAR. A word that wants To expand the body. To embrace until Annihilation. A word that wants To be near, To be more, To be where A word gives up. Someone hears Someone else gasp In his name, Rips him From the dictionary. Someone smells Someone else’s fear In their hair. He burns grass. Someone tastes lamentation With his fingernails. Drools on an envelope. The word NEAR. A word that wants From someone Who is someone To be, To be More and more a word That cannot Fall asleep In any other Words, A word That cannot Be Nobody. The word folds The word FOLDS An image Over an image. Meaning Doesn’t increase. Only the terror Of coincidences Is assessable enough And the edges More clearly Marked By paradoxes. Another today Folds itself Into the word ONCE And into the word That does not see. Concealment Is an axiom. Masters of origami Are known To hide Between their own Fingers Without stopping Their time-consuming Task. Like the hands Fold Paper, Time Folds Words. Little birds, little ships, Hats made from Old magazines Are massacres, Epidemics. A cataclysm folded over A motorcyclysm. A surreal Cynicism? Image over Image. Memory Folds you Into the indifferent Word ONCE And the word That is not visible. October 2019Robert Duncan Web Feature:

Introduction: America Runs on Duncan

By Adam Fales Robert Duncan, “Self-Portrait” (1939), featured on the cover of Chicago Review 45:02

Robert Duncan often wrote in multiple directions at once. His poems, laden with allusions and images, dart around the page as they explore art, myth, and intimacy through polyvalent movements of wordplay and allusion. Similarly, celebrating a centenary involves thinking across multiple temporalities. While the event marks a hundred years since someone’s birth, we more properly celebrate all the life that followed from that birth as well as the legacies that will endure past this hundred-year mark. Any such easy marking of dates seems even more complicated in the case of Duncan, whose personal mythology stretched from his adoptive childhood in California, back to Homeric epics, upward to astrological signs, and inward to psychoanalytically inspired explorations of our subconscious life.

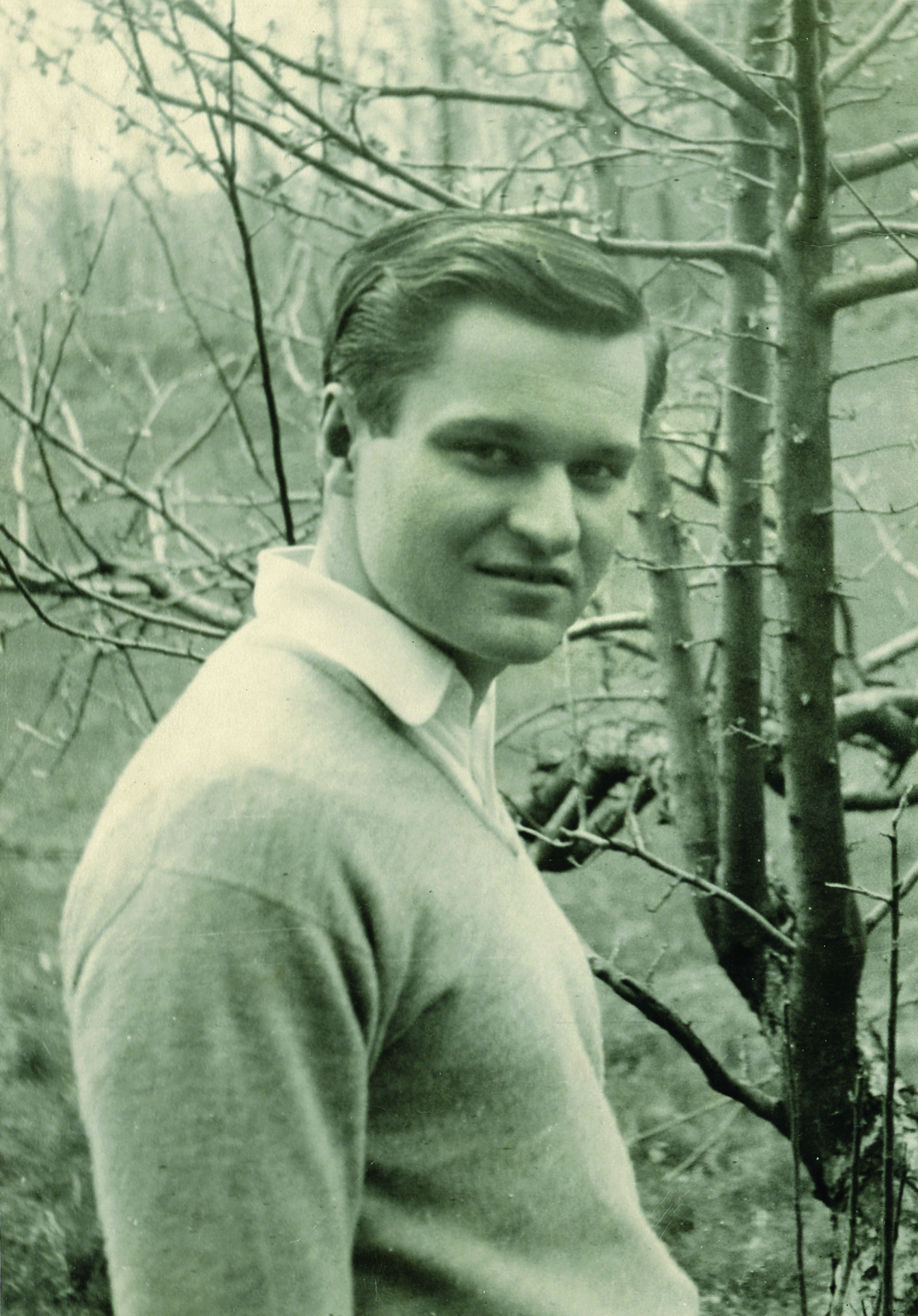

January 7, 2019 marked the 100th anniversary of Robert Duncan’s birth. We take this opportunity to return to some of Duncan’s past work published in Chicago Review, which we are happy to say was a frequent home for his writing over the years. This web feature includes two poems published in 1958 and 1959 and selections from a 1976 interview with Duncan, conducted by Robert Peters and Paul Trachtenberg and first published by CR in 1997. Along with Duncan’s self-portrait and a childhood photograph, these selections span Duncan’s career and life. The earliest of these illustrates Duncan’s childhood that intimately shaped his poetry, whereas the interview captures Duncan as he prepared for his final major project: Ground Work (1984). This breadth of documents testifies to the expansiveness of Duncan’s work and its varied influences and materials. We also include two commentaries on Duncan’s work, one by longtime friend and collaborator Helen Adam, along with a poem that Adam wrote about Duncan toward the end of his life, as well as Duncan’s own introduction to his work, delivered at the Poetry Center in San Francisco.

This feature’s two visual contributions capture images of Duncan before his writing career really began. The 1921 photograph portrays the setting of his mythologized childhood. The young Duncan (then christened Robert Edward Symmes) stands in a garden in Alameda, California, where his adoptive family lived until 1927. The child turns in two directions simultaneously, inspecting something with his hands—perhaps a leaf picked from one of the plants that surround him—while his head turns toward the camera that captures the moment. There’s a similar divergence of attention in his 1939 self-portrait, drawn with wax crayon. Duncan’s likeness stares calmly, resting his head as his nude body extends outside the frame, extruding into the life that animates the portrait. This calm depiction changes when we consider the production of this self-portrait: rendering his body as passive, at rest, Duncan elides the very process of composition. The active body drawing with the crayon calls attention to its own artifice through this very elision. The separation of a representation from the object to which it refers fascinated Duncan throughout his poetic trajectory, especially shaping his early poetry.

Duncan was first published in CR 12.1 (1958) under Irving Rosenthal’s editorship. The poem “Upon Taking Hold” appeared in the contentious “From San Francisco” feature, alongside work by Beat writers Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, William S. Burroughs, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, and others. Compared to something like Burroughs’s Naked Lunch, Duncan’s poem probably did not directly contribute to the University of Chicago’s censorship of CR and Rosenthal’s subsequent resignation along with most of the rest of the editorial staff. (This episode is detailed in Eirik Steinhoff’s essay, “The Making of Chicago Review: The Meteoric Years” in CR 52.2/3/4 as well as our forthcoming Big Table web feature.) However, “Upon Taking Hold,” dedicated to Charles Olson, captures a less overt but still vivid sensuality at play in all of Duncan’s poetic creation: “It is to grasp or to measure / a hand’s breadth, / this hand—mine / as I write—.” These lines collapse the objects and agents of representation, allowing these images to ricochet through meditations on the paintings of Paul Cézanne and echoing Duncan’s early experimentation with visual representation in his self-portrait. His play of visual and verbal representation manifests in the phonic and graphic similarities of words, such as his juxtaposition of the words “altered” and “altar,” which turn “the poetry—now—a gesture” laden with concrete and tangible qualities.

Poetry’s gestural qualities also shape Duncan’s poem “The Natural Doctrine,” published in CR 13.4 the following year. The poem meditates on possible inspirations from nature and artifice. Pondering the wonders of nature, language, and the divine, Duncan hopes: “there may be such power in a certain passage of a poem / that eternal joy may leap therefrom.” To resolve these deliberations, Duncan again turns to pictorial representation, quoting J. M. W. Turner’s last words “The Sun is God, my dear” before adding that “the actual language is written in rainbows.” This modified quotation collapses the many materials that compose the poem—the Sun, God, and Language—to inscribe a linguistic underpinning in purely natural phenomena. However, this gesture, which establishes a privileged position for poetry, removes surety in the authority of that written expression, as nobody actively writes this “actual language.” Poetry occurs in the passive voice; it “is written.”

Duncan thought poets must discover such language, rather than craft it authoritatively in their hands. This conviction led the poet to spend his life occupied with intellectual friendships, collaborations, classrooms, and other forms of experimental thinking together, such as in his time at Black Mountain College, where he taught theatre and poetry and worked closely other artists like Olson. Some of this energy is captured in his free-wheeling interview, conducted by Peters and Trachtenberg and excerpted here. In the interview, Duncan discusses the politics of literary publishing, including John Crowe Ransom and the Kenyon Review’s treatment of him as a gay writer, his interest in Jung and H.D., and his hiatus from publishing and preparation for Ground Work, the first volume of which would be published, eight years after this interview. As the interview conveys the power of Duncan’s vision, it also exhibits some of its limits, especially pertaining to race and gender. Such moments let us examine our political and aesthetic pasts from multiple directions, as Duncan might have done—recognizing their achievements alongside their errors—as well as the work yet to do in our own present. Even as we celebrate the past, we might also reconsider the future of poetry and its politics.

Duncan’s centenary year shares the bicentenaries of similarly exploratory American writers Herman Melville and Walt Whitman. His work shares the same enthusiastic sensuality that these earlier writers seized through their own literary experiments. In many ways, he expresses possibilities that these earlier queer writers would not have thought possible. Duncan moves us to explore many more directions, looking to the future and imagining the potential, as-yet-unimagined, unfoldings of literary experimentation. Happy 100th Birthday, Robert Duncan.

Visit the Robert Duncan Web Feature.

Robert Duncan, “Self-Portrait” (1939), featured on the cover of Chicago Review 45:02

Robert Duncan often wrote in multiple directions at once. His poems, laden with allusions and images, dart around the page as they explore art, myth, and intimacy through polyvalent movements of wordplay and allusion. Similarly, celebrating a centenary involves thinking across multiple temporalities. While the event marks a hundred years since someone’s birth, we more properly celebrate all the life that followed from that birth as well as the legacies that will endure past this hundred-year mark. Any such easy marking of dates seems even more complicated in the case of Duncan, whose personal mythology stretched from his adoptive childhood in California, back to Homeric epics, upward to astrological signs, and inward to psychoanalytically inspired explorations of our subconscious life.

January 7, 2019 marked the 100th anniversary of Robert Duncan’s birth. We take this opportunity to return to some of Duncan’s past work published in Chicago Review, which we are happy to say was a frequent home for his writing over the years. This web feature includes two poems published in 1958 and 1959 and selections from a 1976 interview with Duncan, conducted by Robert Peters and Paul Trachtenberg and first published by CR in 1997. Along with Duncan’s self-portrait and a childhood photograph, these selections span Duncan’s career and life. The earliest of these illustrates Duncan’s childhood that intimately shaped his poetry, whereas the interview captures Duncan as he prepared for his final major project: Ground Work (1984). This breadth of documents testifies to the expansiveness of Duncan’s work and its varied influences and materials. We also include two commentaries on Duncan’s work, one by longtime friend and collaborator Helen Adam, along with a poem that Adam wrote about Duncan toward the end of his life, as well as Duncan’s own introduction to his work, delivered at the Poetry Center in San Francisco.

This feature’s two visual contributions capture images of Duncan before his writing career really began. The 1921 photograph portrays the setting of his mythologized childhood. The young Duncan (then christened Robert Edward Symmes) stands in a garden in Alameda, California, where his adoptive family lived until 1927. The child turns in two directions simultaneously, inspecting something with his hands—perhaps a leaf picked from one of the plants that surround him—while his head turns toward the camera that captures the moment. There’s a similar divergence of attention in his 1939 self-portrait, drawn with wax crayon. Duncan’s likeness stares calmly, resting his head as his nude body extends outside the frame, extruding into the life that animates the portrait. This calm depiction changes when we consider the production of this self-portrait: rendering his body as passive, at rest, Duncan elides the very process of composition. The active body drawing with the crayon calls attention to its own artifice through this very elision. The separation of a representation from the object to which it refers fascinated Duncan throughout his poetic trajectory, especially shaping his early poetry.

Duncan was first published in CR 12.1 (1958) under Irving Rosenthal’s editorship. The poem “Upon Taking Hold” appeared in the contentious “From San Francisco” feature, alongside work by Beat writers Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, William S. Burroughs, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, and others. Compared to something like Burroughs’s Naked Lunch, Duncan’s poem probably did not directly contribute to the University of Chicago’s censorship of CR and Rosenthal’s subsequent resignation along with most of the rest of the editorial staff. (This episode is detailed in Eirik Steinhoff’s essay, “The Making of Chicago Review: The Meteoric Years” in CR 52.2/3/4 as well as our forthcoming Big Table web feature.) However, “Upon Taking Hold,” dedicated to Charles Olson, captures a less overt but still vivid sensuality at play in all of Duncan’s poetic creation: “It is to grasp or to measure / a hand’s breadth, / this hand—mine / as I write—.” These lines collapse the objects and agents of representation, allowing these images to ricochet through meditations on the paintings of Paul Cézanne and echoing Duncan’s early experimentation with visual representation in his self-portrait. His play of visual and verbal representation manifests in the phonic and graphic similarities of words, such as his juxtaposition of the words “altered” and “altar,” which turn “the poetry—now—a gesture” laden with concrete and tangible qualities.

Poetry’s gestural qualities also shape Duncan’s poem “The Natural Doctrine,” published in CR 13.4 the following year. The poem meditates on possible inspirations from nature and artifice. Pondering the wonders of nature, language, and the divine, Duncan hopes: “there may be such power in a certain passage of a poem / that eternal joy may leap therefrom.” To resolve these deliberations, Duncan again turns to pictorial representation, quoting J. M. W. Turner’s last words “The Sun is God, my dear” before adding that “the actual language is written in rainbows.” This modified quotation collapses the many materials that compose the poem—the Sun, God, and Language—to inscribe a linguistic underpinning in purely natural phenomena. However, this gesture, which establishes a privileged position for poetry, removes surety in the authority of that written expression, as nobody actively writes this “actual language.” Poetry occurs in the passive voice; it “is written.”

Duncan thought poets must discover such language, rather than craft it authoritatively in their hands. This conviction led the poet to spend his life occupied with intellectual friendships, collaborations, classrooms, and other forms of experimental thinking together, such as in his time at Black Mountain College, where he taught theatre and poetry and worked closely other artists like Olson. Some of this energy is captured in his free-wheeling interview, conducted by Peters and Trachtenberg and excerpted here. In the interview, Duncan discusses the politics of literary publishing, including John Crowe Ransom and the Kenyon Review’s treatment of him as a gay writer, his interest in Jung and H.D., and his hiatus from publishing and preparation for Ground Work, the first volume of which would be published, eight years after this interview. As the interview conveys the power of Duncan’s vision, it also exhibits some of its limits, especially pertaining to race and gender. Such moments let us examine our political and aesthetic pasts from multiple directions, as Duncan might have done—recognizing their achievements alongside their errors—as well as the work yet to do in our own present. Even as we celebrate the past, we might also reconsider the future of poetry and its politics.

Duncan’s centenary year shares the bicentenaries of similarly exploratory American writers Herman Melville and Walt Whitman. His work shares the same enthusiastic sensuality that these earlier writers seized through their own literary experiments. In many ways, he expresses possibilities that these earlier queer writers would not have thought possible. Duncan moves us to explore many more directions, looking to the future and imagining the potential, as-yet-unimagined, unfoldings of literary experimentation. Happy 100th Birthday, Robert Duncan.

Visit the Robert Duncan Web Feature.

On the Infrarrealistas Issue and José Vicente Anaya

To the Editors:

In the spirit of continuing the work that Chicago Review has begun by making Infrarealist writing available in John Burns’s excellent translations, I feel compelled to point out a conspicuous lacuna in the portfolio from issue 60.3—the exclusion of José Vicente Anaya. Despite the fact that he was a founding member of the Infrarealists, wrote one of the group’s three manifestos (perhaps the first), and was included in Pájaro de calor: Ocho poetas Infrarrealistas (the Infrarealist anthology published in 1976), Anaya has been relegated to a couple footnotes in Rubén Medina’s Infrarealist portfolio. He haunts the dossier, appearing in photos and on flyers, but his writing is not represented. As Vicente’s friend and translator, I would like to address some of the issues surrounding his exclusion, and offer some of his work to fill in the gap. I respect the fact that Medina was a member of the group in the seventies and so has extensive firsthand information—this is apparent in his introduction—but as with any history, especially one that has been subject to so much popular myth, legend, and fictionalization as that of Infrarealism, there are multiple perspectives and representational struggles. Of course, Roberto Bolaño—who in any case is responsible for the current surge of interest in the Infras—seized the dominant narrative and crafted himself and Mario Santiago as the centers of gravity around which other poets orbited. Medina, without exploding this myth too much (anything with Bolaño is great for marketing), seems to have taken over in his self-appointed role as official administrator of the legacy of Infrarealism. Medina also edited a Spanish-language anthology in which Anaya—along with the poets Lisa Johnson and Lorena de Larrocha—was redacted. Since Medina has positioned himself as the gatekeeper of Infrarealism, it seems unlikely that Anaya’s exclusion was disclosed to Chicago Review, but it is worth pointing out that there is a precedent for publicly addressing the issue. When the Spanish-language Infrarealist anthology was published, the popular Mexican magazine Proceso ran an article including Anaya’s perspective called “An Exclusionary and Censored Anthology.” I have to say, Medina’s editorial habits are quite ironic, as he has come to embody exactly what Infrarealism positioned itself against: in Medina’s own words, “the outsized authority and influence of a single figure.” In his censorship, self-canonization, and self-promotion, Medina has reproduced the status quo that the Infrarealists originally opposed. Medina attempts to justify the exclusion from Chicago Review with a short sentence buried at the bottom of footnote one: “Anaya left the group in 1976.” The slightest bit of research exposes the emptiness of such a justification, leaving it unclear exactly why Medina and Burns have chosen to retrospectively purge him. Anaya left Mexico City at the end of 1977 to bum around Mexico for four years, shortly after Bolaño left for Spain. They both left during what Anaya calls the “Infrarealist diaspora,” when many original members dispersed and moved abroad. If I’m not mistaken, Medina himself left for California shortly afterwards. Anaya denies breaking with the group; he claims, as has Bolaño, that Infrarealism ended after the diaspora. This is obviously contentious; there are varied perspectives here, from Bolaño’s narcissistic assertion that he and Mario Santiago were the only Infrarealists, to those who believe that the Infras are still a current movement that includes young poets born after the diaspora. I am not in any position to say who is right or wrong in this; in fact, I tend to agree with what Heriberto Yépez said in an interview with Anaya in Replicante magazine: that the three manifestos presented three different visions of the movement, that there were always several different Infrarealisms.[1] In the end, this is all mostly irrelevant to the undeniable fact that Anaya was an Infrarealist and therefore deserves a place in the group’s archive. To be clear, Anaya was an active part of the movement at its inception and during its most notorious years. That Medina and Burns refused to include, at the very least, Anaya’s manifesto is baffling. In an attempt to remedy this exclusion, I present a translation of Anaya’s Infrarealist manifesto, “For a Vital and Unlimited Art,” along with the poems “Morgue 1,” “Morgue 2,” and “Conversation with Armando Pereira.”[2]Joshua Pollock

Notes: [1] José Vicente Anaya and Heriberto Yépez, “Los infrarrealistas…Testimonios, manifiestos y poemas,” Replicante 3.9 (2006): 137. [2] Editorial Note: Chicago Review will be publishing Joshua Pollock’s translations of these pieces by Anaya, along with a brief introduction, in our next issue (63.3).“How to manage the heat”: On Gerrit Lansing

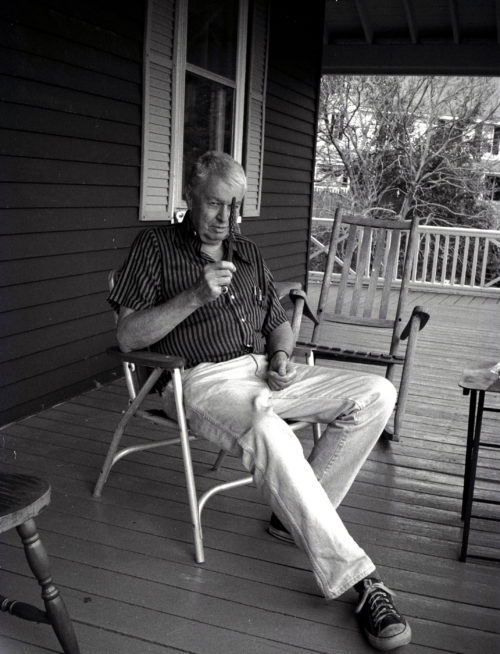

by Pierre Joris Gerrit Lansing, Gloucester, MA, (1992). Photo by Pat Smith, image courtesy of Pierre Joris.

Gerrit Lansing, Gloucester, MA, (1992). Photo by Pat Smith, image courtesy of Pierre Joris.

1. A Life

Gerrit Lansing passed away February 11, 2018, in Gloucester, Massachusetts. A man of wider & deeper knowledge than almost anyone I have known, Lansing was as familiar with, & brought as much care to, contemporary poetry & poetics as to older literatures, to the traditionary sciences as to modern science, to the making of music as to the preparing of food. A conversationalist nonpareil, he moved with grace, enthusiasm & profound savoir & savoir-faire from, say, a poet such as Henry Vaughan to his friend Charles Olson, or from the likes of John Dee to the likes of Harry Smith, or from Roland Barthes to Stephen Jonas—& knew the traceries that connected all of them. Before I try to address the work, let his hometown newspaper, the Gloucester Times, have the first word with its (anonymous) obituary of Lansing’s exoteric life:Gerrit Yates Lansing was born on February 25, 1928, in Albany, N.Y., the son of Charles B. and Alice (Scott) Lansing. After a brief stay in Colorado Springs, Gerrit and his family moved to the Cleveland area, where his father, an engineering consultant and metals executive, served as Chairman of the Western Reserve University board of trustees. At Harvard College, which Gerrit graduated from in 1949, his social set included the artist Edward Gorey, poets Frank O’Hara and John Ashbery, and childhood friend Kenward Elmslie. After graduation, Gerrit moved to New York City, working for Columbia University Press, and receiving a master’s degree from Columbia in 1955. In the heady atmosphere of 1950s New York City, Gerrit partied with theatrical and literary celebrities too numerous to mention, but the stand out figure in his social circle was the lyricist John LaTouche, who at one point hired Gerrit to adapt the writings of H.P. Lovecraft into a film treatment. Through LaTouche and Harry Martin, Gerrit befriended the inventor John Hays Hammond Jr., prompting Gerrit to move to Gloucester, where he initially lived in Hammond Castle. In Gloucester, Gerrit met two men who greatly shaped his life: poet Charles Olson and sailor Deryk Burton. Olson he surprised with an unannounced visit to the poet’s Fort Square apartment. Gerrit became not only a friend and correspondent with Olson, but also the quiet expert on the role of tarot, astrology, and the estoreric on Olson’s writings and thought. At the Studio Restaurant on Rocky Neck, Gerrit met the love of his life, Deryk Burton, a sailor born in Wallasey, England, who skippered private yachts. Together, Gerrit and Deryk sailed these vessels to their winter berths in Florida and the Carribbean. Intrigued by the occult since high school, Gerrit became an encyclopedic resource on the topic, opening his bookstore Abraxas, which specialized in magic, philosophy, and rare esoteric volumes.

It seems to me that Gerrit would have delighted in that misspelled word “estoreric” for esoteric—in fact I wouldn’t be surprised if it was his mischievous humor that returned in the shape of a typo-gremlin to slip that coquille, as the French say, that (oyster, clam, whatever) shell into his own obit.2. An Approach

If, as the above summary shows, Lansing delighted in & took full advantage of the avant-garde & anticonformist 1950s—at both the personal sexual & the wider artistic levels—that life in New York City made possible, there came however a moment when another side of Gerrit’s made itself felt: his love & need for an actual daily connection to the nonurban, to nature. Settling in Gloucester fulfilled this (& all the other facets of his) character. Besides the city’s duality—& the dual was dear to him, see the appendix to the editorial/manifesto “The Burden of SET #1” of issue one of his magazine SET (of which, by the way, there would only be two issues)—of sea & land & all that entailed, there was the delight in wild walks (I remember him showing us Dogtown Commons, which under his guidance took on another dimension than it had in Olson’s Maximus Poems), in his mushrooming & herbalizing (I made that word up & autocorrect immediately changed it to “verbalizing”—unless that was the Gerrit-gremlin again: both are accurate indeed). Thus the intricate duality of nature & culture—“kulchur,” he spelled it elsewhere, quoting Ezra Pound, & “cultsure” when he criticized its reactionary priestly embalmers—weaves together (“to tether” the Gerrit-gremlin corrected) the life & work into a richly complex fabric. How to approach this work now, after the disappearance of il miglior fabbro, as Dante called Daniel, & Eliot, Pound? One way into the thought & work would be via his own identification in an interview with Charles Bernstein & Susan Howe: “From the very beginning I regarded myself as Emersonian in many ways—because of Whitman…and as Robert Duncan is in many ways.” No better entry, then, into Lansing than to reread the opening paragraph of Emerson’s “Nature”:Our age is retrospective. It builds the sepulchres of the fathers. It writes biographies, histories, and criticism. The foregoing generations beheld God and nature face to face; we, through their eyes. Why should not we also enjoy an original relation to the universe? Why should not we have a poetry and philosophy of insight and not of tradition, and a religion by revelation to us, and not the history of theirs? Embosomed for a season in nature, whose floods of life stream around and through us, and invite us by the powers they supply, to action proportioned to nature, why should we grope among the dry bones of the past, or put the living generation into masquerade out of its faded wardrobe? The sun shines today also. There is more wool and flax in the fields. There are new lands, new men, new thoughts. Let us demand our own works and laws and worship.

And that is exactly what Lansing set out to do, in the poems as much as in the two essential essays (editorials, he calls them)—“The Burden of SET” #1 & #2—that constitute his theoretical-practical advice on how to go about living & making art here, in & under America’s dispensation.3. SET #1

In 1961, Lansing saw the need for a magazine of poetry, actions & community (see #5) & created SET—the polysemic title resonates from jazz to tennis (well, in a minor, more humorous way) to stance (I hear as the Olsonian term but also as Paul Celan’s “stehen,” as equivalence to being alive, still) to Egyptian hermetic godhead—which will be “fix & dromenon / & to the poem.” The inside front cover starts with the word “onset” & then, to the right & further down, begins a poem/statement he will elaborate on in the essay/manifesto “The Burden of SET #2”:o.k. let it come down, in on us, all of it, so much as we can, & then to get it out again. That was an Epitome of Yoga…“SET still, stop thinking, shut up, get Out,” & yoga is concentration of experience (exclusion too, yes, but not of experience itself, rather of experiences not really experienced enough, restraint of the modifications of mind in order to feel their source) whose enemy is abstraction, distraction, retraction, any thing or way that hinders the going traction.

An “epitome of yoga,” & indeed this is an excellent description of the process of that art/discipline which Lansing practiced throughout his life, but it is also, & especially as set here at the head, the “onset” of the magazine, an epitome of poetry. These directions for poetry are developed in more (the Gerrit-gremlin changed that momentarily & inexplicably to “kore” thus bringing in “core” but also Kore, or Persephone, the queen of the underworld) detail in his “editorial”—set further in the body of the magazine as it comes after work by Duncan, Olson & Stephen Jonas. Work of the latter, in fact, surrounds the editorial, showing the importance Jonas had, as a friend & poet, for Lansing. The character of these poetic explorations, “here & especially now,” are “conceived as dual, historical & magical, the emphasized characters of Time.” Lansing goes on to develop these characters of Time in what to this day remains one of the clearest & most useful statements of an active poetics we have.4. The Temptation

now would be to pull, to cut back my own words, to just quote, cite, inscribe Lansing’s words, the full essays, then the poems—they speak loud enough & better than I can. Can’t do this, however, have to speak up & honor GL, in a laudatory manner his own modesty & discretion would never have permitted him to do. But, this hint: even before reading this homage, get, buy, order, or steal these two books: Heavenly Tree, Northern Earth, which is a collected poems (at least of those poems GL wanted to retain) augmented by the two Burdens of SET essays (North Atlantic Books, 2009, lovingly designed by poet Jonathan Greene & worth to have in its inexpensive hardback); & A February Sheaf, a sort of selected (“uncollected, old and new”) poems followed by a large (seventy pages) section of “reviews, essays, gists,” which gather all such prose writings, including the two SET editorials, Lansing wanted to make public. It was published in 2003 by Pressed Wafer, the press founded by William Corbett, recently deceased poet & friend who, in their long barzakh, will be companion-traveling side by side with Gerrit.5. The Company, or a Constellation, i.e. Breaking Bread

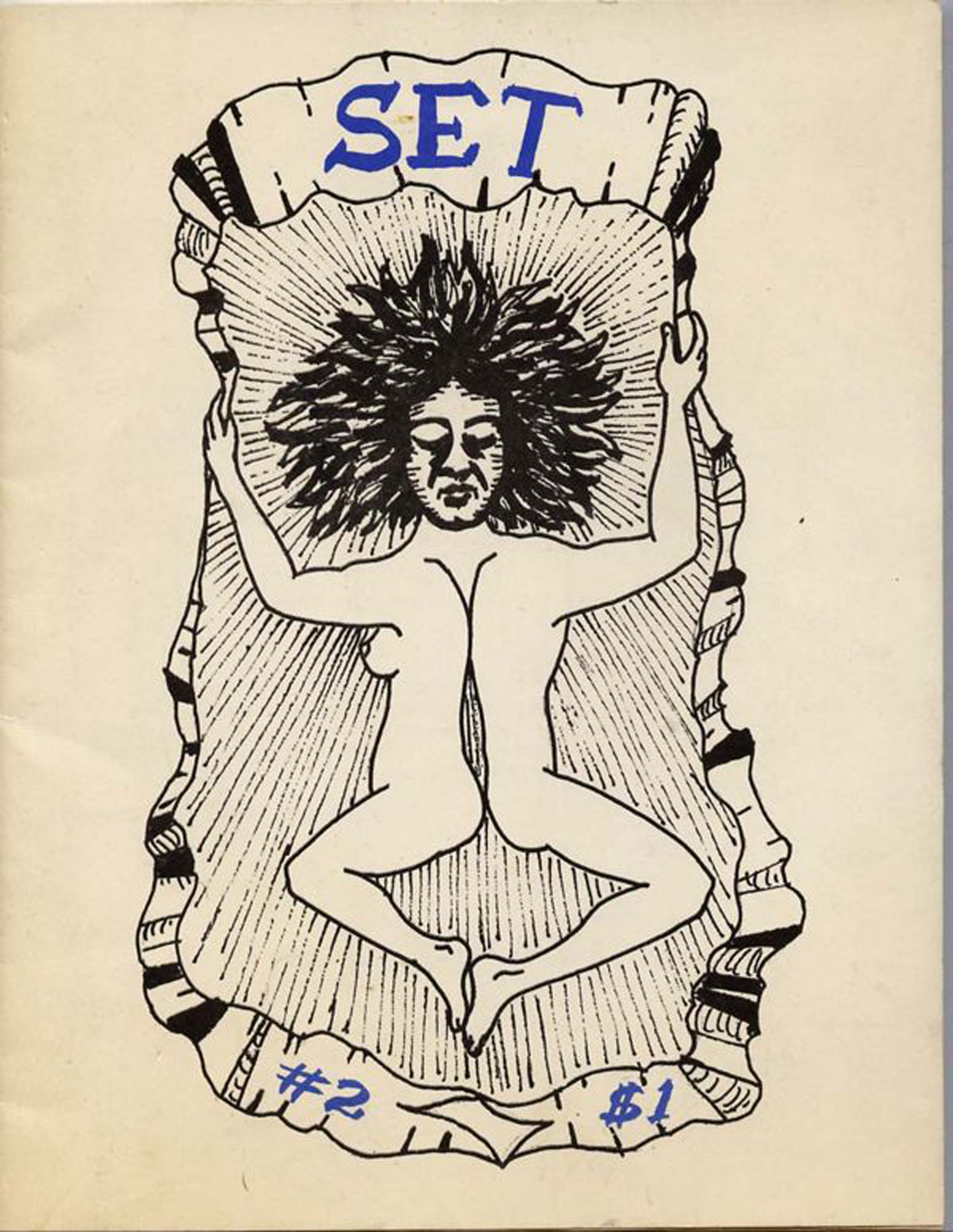

Long ago, coming into American poetry & before I even knew of Lansing, I read an interview with Robert Creeley in which he was asked if he had any advice for young poets. “Company” was his answer, or more exactly: “I think company is immensely useful, by which I mean finding some company that lets one feel respect and less than paranoid about what it is one cares for.” For the European I was back then & for whom the image of the poet as isolato, holed up in some ivory tower, was still somewhat active, this discovery was major. (As was GL’s thinking about the culture I came from, pithily put in the second of the Burden of SET essays: “European whiteness is sepulcher to us & European consciousness a museum”—I have ever since worked at overcoming that heritage.) The poet who gave Lansing to me by giving me a copy of his first book—The Heavenly Tree Grows Downward (Matter Books, 1966) (I still cherish that long “legal size” mimeographed & side-stapled item with green covers & yellow-orangey inside pages printed in brown ink)—was Robert Kelly. And Kelly also spoke of the magic of “company” in an interview where he said: “The individuals back then, you ask about them. What a great company we were, what a fantastic chevere I was permitted to be part of. The company of those days—like Gerrit Lansing’s wonderful phrase ‘the company of love / safe in the garden that is themselves.’ How can anyone work without a company?” “Company” comes from “con pan”—literally “with bread”—to share bread, to break bread with someone, & this action, to cook & share food around a table in talk, was an essential part of Lansing’s art of living. The company he held was manifold, but besides the New York poetry scene’s denizens already mentioned above, it is necessary to mention three or four other companies, distinct from each other though overlapping in various ways. There is of course the local Gloucester area community of friends, too innumerable to list here. Let me just mention those I had the pleasure of being introduced to by Gerrit, & which included artists & writers such as Thorpe Feidt, Amanda & James Cook, John Giglio, Kristine Roan, Patrick Dowd, Joe Torra, Jim Dunn, und so weiter. Beyond Cape Anne is the Boston group of poets, “the occult school” (dixit GL) that includes (with John Wheelwright as forerunner) John Wieners (who prefaced Gerrit’s first book of poems) & Stephen Jonas (whose literary executor Lansing would become, together with Raffael de Gruttola) & further away the likes of Jack Spicer & Robin Blaser on their passage through Boston. The latter also indicates the company’s overlap with the Black Mountain group, Olson of course, & Duncan, but also Creeley & Ed Dorn. Beyond that, Lansing was a major influence on & friend of what I like to call the Ta’wil poets, among them Robert Kelly, Kenneth Irby, Charles Stein, Don Byrd & George Quasha. Or another more diffuse constellation affiliated with the Beats & beyond would include Diane di Prima, Amiri Baraka, Diane Wakoski, etc. But such a diagrammatic literary layout does not give the full picture: Gerrit was open to every man or woman that he met, giving every visitor, old friend or new acquaintance, his undivided attention. As Nicole Peyrafitte (who is currently working on a documentary film on Gerrit Lansing) put it: “Gerrit’s was a unique presence, and I mean unique because he had the incredible gift of making a multilevel personal connection not only at the moment of the encounter, but one that would remember every detail over the years. It was as if each of his friendships had its own DNA that recorded each particular of that specific relationship.” Driving to Gloucester to visit Gerrit for an afternoon or a day or more was always at least a double pleasure for us: the pleasure to see Gerrit & the surprise pleasure of meeting old or new friends who were already there, sitting around the table, breaking bread, sharing food, drink, & talk… Front cover of SET #2 (Winter 1963-64), drawing by Harry Martin. Image courtesy of Pierre Joris. Copyright the Estate of Gerrit Lansing.

Front cover of SET #2 (Winter 1963-64), drawing by Harry Martin. Image courtesy of Pierre Joris. Copyright the Estate of Gerrit Lansing.

6. SET #2

The cover of the second issue of SET is a drawing by Lansing’s friend Harry Martin representing a hermaphroditic figure. Before, or besides, associating this figure with the traditionary sciences, which were a lifelong interest & practice of Lansing’s, we can also directly link it to the realm of poetry. In his essay “François Villon,” the great Russian poet Osip Mandelstam writes: “The lyrical poet is a hermaphrodite by nature, capable of limitless fissions in the name of his inner monologue.” In an essay from the mid-eighties on Mandelstam & Bakhtin, “Dialogue as ‘Lyrical Hermaphrodism,’” Svetlana Boym comments as follows: “Mandelstam’s ‘lyrical hermaphroditism’ does not signify a Platonic ideal of androgynous wholeness, a reconciliation of two polarities. On the contrary, it is viewed as a peculiar kind of poetic dvupolost (hermaphroditism) that reveals multiple splittings of the poet’s self and suggests an open-ended and continuous interplay of sexual and social roles, of nuances of intonation and artistic styles.” Lansing himself, in the editorial of SET #2, creates a fascinating dual layout that mirrors in a way the cover figure: Gerrit Lansing, diagram from SET #2 (Winter 1963-64). Image courtesy of Pierre Joris. Copyright the Estate of Gerrit Lansing.

Gerrit Lansing, diagram from SET #2 (Winter 1963-64). Image courtesy of Pierre Joris. Copyright the Estate of Gerrit Lansing.

7. A Writ a Route a Root a Rite

“A writ is a route,” Lansing wrote in his great sequence “The Soluble Forest,” & he traced this route in one book, one exfoliating gathering of poems, reorganized & added to over time, republished in time, & that started out with the already mentioned 1966 edition of The Heavenly Tree Grows Downward by Robert & Joby Kelly’s matter books. Jane Freilicher’s portrait of Lansing (reproduced opposite) was the frontispiece of that book. In his preface, John Wieners begins by commenting on the title, saying that “the title is wrong; alchemically it is right; but the essence of purpose is not downward. It is upwards toward heaven…. These poems reach that way. // And the devil steps between each word.” The devil’s step is the necessary dance the reader has to do to follow the route the poem traces. I would caution the reader not to take Wieners at his word exactly: this is not a Christian or similar transcendental metaphysics where “heaven” is up in the sky while we lowlifes are mired in this material world inescapably, or at least until death. Gershom Scholem, the great scholar of Kabbalah, suggested that in these days of “a great crisis in language”—& culture, I’d like to add—where the older knowledges & traditions such as Kabbalah & the various hermetic traditions &, most importantly at this ecological turn of our Anthropocene, those traditional knowledges concerning botany, geology & the animal kingdoms, where all those realms of knowledge have fallen silent & in disrepute, we must turn toward those “who still believe that they can hear the echo of the vanished word of the creation in the immanence of the world.” And Scholem goes on: “This is a question to which, in our times, only the poets presumably have the answers.”8. Opacity

Yes, the poems are not transparent, & yet, as Wieners also says in his foreword to The Heavenly Tree Grows Downward: “The obtuse is clarity.” Lansing, in that sense, writes in a different tradition than that of his old New York School friends. Or has different aims, even given the often humorously witty surface, debonairly urbane (& more open in terms of the language he uses) as any O’Hara poem, especially in matters of the sexual. Thus the poem entitled “The Joint Is Jumping” starts with the lines, “Whose joint? Pass me one, please, / et suçe ma bite. What’s the time?” though the sexual, core to Lansing’s work, is more often linked to Reichian, Crowleyan, or tantric themes. In the poem just mentioned, the second stanza has moved this theme elsewhere: “We lop the moon, invoking hazard’s sorites / our sorties through the orient gates.” I link the “orient” of those (Blakean) gates “where we slither out of time” to aspects of esoteric Sufism, as laid out in Henry Corbin’s work. Lansing’s realm, what Kenneth Irby calls his kosmanthropologia, I see as corresponding to that in-between realm, “ontologically as real as the world of the senses and that of the intellect,” Corbin finds in Sohrawardî & others where it is called ‘âlam al mithâl, the world of the image, the mundus imaginalis. This realm is opened by the creative imagination, an organ of both perception & creation, & which for the poet becomes incarnated in the multilayered, polysemantic & -symbolic levels of language, where both the writing & the reading of the text presuppose a hermeneutic act. In the esoteric Sufi tradition this specific hermeneutic act is called ta’wil, a concept that Tom Cheetham, our best commentator on Corbin, describes as follows: “The apprehension, the reading and understanding of these symbols, is not merely an intellectual exercise but an exegesis that transforms the soul—it is spiritual exegesis,” because (Corbin again) “the ta’wil enables men to enter a new world, to accede to a higher plane of being.” In that sense, a poem can be seen, writes Robert Kelly, as “the ta’wil of the first word written down.” To return to that deep root of Lansing’s work, the sexual as transformative action that links the various realms—as much as poetry does?—here is a line from another poem: “Sex on earth is rhymed angelic motion.” Unsurprisingly, this can make for symbolically multilayered “obscure” or “esoteric” poems, but I’d like to suggest that all poetry in the lineage of a visionary poetics (in the lineage of, say, Blake, Hölderlin, Rimbaud, & even Whitman) presents, has to present, an often opaque though never impenetrable surface. In a prose fragment Celan put it this way:Imagination and experience, experience and imagination make me think, in view of the darkness of the poem today, of a darkness of the poem qua poem, a constitutive, thus a congenital darkness. In other words: the poem is born dark; it comes, as the result of a radical individuation, into the world as a language fragment, thus, as far as language manages to be world, freighted with world.

But such darkness is never a willed obscurity, an obscurity created for the sake of itself; it corresponds rather to the real darkness that surrounds us & that is inside us as much as it is inside the outside world. The poem does not try to throw some “light” (or fake “light-ness”) on either inside or outside worlds. This darkness should not, however, discourage us, but should remind us to read poets like Lansing & Celan with negative capability, i.e., with what Keats defined as the needed ability to be “in uncertainties, Mysteries, doubts without any irritable reaching after fact and reason.” Lansing himself was fully aware of this, & in an essay on the work of Clark Coolidge, after citing Pound telling William Carlos Williams that “the thing that saves your work is opacity, and don’t you forget it. Opacity is not an American quality,” he goes on: “that was true then, but by now [1987] native American instances of opacity have become much more visible.”9. Alchemy