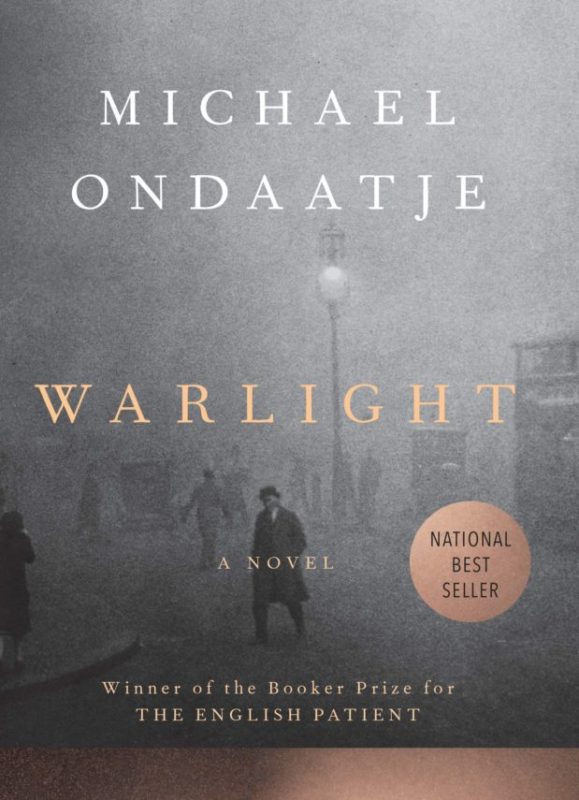

Michael Ondaatje, Warlight: A Novel

Reviewed by Brandon Truett

Immersed in the bewildering atmosphere of post-WWII London, Michael Ondaatje’s Warlight introduces the narrator, Nathaniel, a fourteen-year-old English boy, and his sister Rachel at the moment when they learn that their parents will abandon them to take up work in Singapore for an undisclosed amount of time. The parents leave the children in the care of guardians, a cast of shadowy figures whose names suggest espionage codenames (The Moth, The Darter, Olive, and McCash) and who have obscure connections to their mother’ s equally sketchy wartime activities. The children gradually acquire information about their mother, who operates as an occluded presence around which the events of the novel circulate. At the age of twenty-nine, Nathaniel tries to make sense of these bizarre events, imbuing the narrative with the character of both a memoir and an investigation, the outcome of which promises a fuller picture of his own past as well as the true identities of his parents and their associates. Indeed, Ondaatje’ s Warlight , which was longlisted for the 2018 Man Booker Prize, is not only what Hermione Lee has called a “novel of chiaroscuro, ” which thematizes light and darkness in manifold ways, but also a narrative experiment that tests the availability of historical memory when one has only flickering candlelight by which to illuminate and interpret the materials of the past.

The most defining feature of Warlight is the overwhelming feeling of darkness that modulates across a range of registers. The title itself refers to the unlit atmosphere of the Blitz, a tense period when London (among other British cities) had to institute blackouts and curfews in order to protect itself from the sight of German bomber planes. Ondaatje heightens the sense that there was only the ghostly presence of warlight, which names the dim illumination that emanated from small orange lights on the bridges along the Thames during the darkness of the Blitz. Much of the novel labors to describe the metaphorical nature of this warlight, which seems to also penetrate the shrouded environment to reveal merely the silhouettes of the characters. As Nathaniel explains: “It was a time of war ghosts, the grey buildings unlit, even at night, their shattered windows still covered over with black material where glass had been. The city felt wounded, uncertain of itself.” Amid the dark setting of bombarded houses live the “war ghosts,” a descriptor that seems to apply to each character in the novel—and even to Nathaniel’ s sister, about whom we do not know much because, as Nathaniel admits, “we have separate memories. ” We learn more about the clandestine activities of The Darter, a welterweight boxer and friend of The Moth, whom Nathaniel assists in the trafficking of illegally imported race dogs along the narrow canals of the Thames. Agnes, with whom Nathaniel carries on his first love affair, also helps with the importation of illegal cargo. In a memorable moment of the novel, Agnes and Nathaniel break into an unlit three-story building in Mill Hill with a pack of greyhounds, and they sleep entangled on the floor. Nathaniel awakes to a paw on his face, and he asks the greyhound, “Where are you from?…What country? Will you tell me?” Unable to answer these questions for himself or those of others around him, Nathaniel later feels an unlikely kinship with the illegitimate race dogs. It is this basic line of questioning—requests for only the most elemental information—that drives the narrative. Deeper questions do not find traction. In many ways, Ondaatje crafts a novel that frustrates the reader’s attempts to dig beneath the surface; we are left feeling our way along the dark pages with our fingers outstretched, flailing in the absence of coherent meaning.

Indeed, the careful orchestration of this feeling-through-darkness marks the masterful achievement of Warlight. Just as Nathaniel feels lost amid his unlit memories, we read with a taut feeling of suspense that Ondaatje never relieves; like Nathaniel, we too feel unable to cohere the narrative events and make sense of them. This quality of suspense is of course a familiar feature of modernist war literature. But more specifically Ondaatje’ s novel revitalizes the genre of postwar novels of the 1940s that sought to mediate the boundless experience of war on the home front. The affective experience of wartime as a kind of darkness that disorients and constricts the human sensorium particularly distinguished novels about the Blitz. For example, the Irish novelist James Hanley conveys in No Directions (1943) the otherworldly nature of wartime London through the isolation that accompanies the threat of aerial bombardment on a block of flats in Chelsea. Fearing the impending destruction that lurks outside, the tenants retreat and are confined to the inside of the building for much of the novel; a painter continues to work on his enormous canvas during the blackouts, in much the same way that Nathaniel writes his memoir under metaphorical candlelight. Even though the characters yearn for the separation of inside and outside, Hanley disrupts this epistemological boundary such that the characters cannot come to grips with the material world. Through tropes of disorientation that short-circuit the nervous system, Blitz novels, such as No Directions and, I would argue, Warlight, intensify the question of mediation, as they contemplate the ways in which the experience of war forecloses the reliable formation of memory. How do you form a memory of a past to which you do not have access? What does it mean to know something when that process of knowing has been impaired?

By creating a character who desperately seeks to remember, Ondaatje insists on the unknowability of a life that is yoked to war. Although Warlight begins in 1945, after the ostensible conclusion of WWII, the most intimate events of the novel are wholly determined by the ongoing effects of the war. As the novel progresses, warlight seems to capture the ways in which the intensity of a totalizing event like war will continue to incandesce; war becomes the essential light source by which we read the world and understand ourselves. Part Two of Warlight, which jumps forward fifteen years to 1959, positions Nathaniel as the investigator of his own life, searching for partial answers to the ungraspable questions that have loomed over the novel, the most important being the identity of his mother and her relation to the war. The Foreign Office offers Nathaniel a job to review the archives from the war and postwar years. While at first Nathaniel sees the job as an opportunity to uncover details about his mother, who we have learned worked in some capacity for British intelligence during the war, he eventually recognizes “that an unauthorized and still violent war had continued after the armistice, a time when the rules and negotiations were still half lit and acts of war continued beyond public hearing. ” Nathaniel participates in what he calls “The Silent Correction, ” a censorship campaign waged on both sides of the war to destroy unsavory documents that might incriminate a country and thus pave the way so that “revisionist histories could begin. ” While his colleagues work to reinvent the narrative of the war, Nathaniel carries out his own revisionist project to discover the more accurate history of his own and his mother’ s lives. Ondaatje maintains over and again the irresolvable tension between life and war—that as a result of its boundlessness, war invades and determines all aspects of life. Nathaniel’ s act of self-discovery, which is tied as much to the war as to his mother, serves as a proxy for the comprehension of the war; just as the story of a life is fraught with silences and elisions, so is the epistemology of war and its effects.

By destabilizing the “post” in postwar through folding in the immediate aftermath with its lingering effects, Ondaatje provides a novelistic exemplar of what Paul Saint-Amour has theorized as the “perpetual interwar,” which describes the condition in late modernity of “the real-time experience of remembering a past war while awaiting and theorizing a future one.” Saint-Amour draws our attention to the historical analysis of “expectation, anxiety, prophecy, and anticipatory mourning ” such that we might avoid “the wartime-versus-peacetime binarism [and] the too simple rejoinder that now all time is wartime.” Ondaatje certainly can be said to participate in the post-1945 genre of contemporary historical novels about WWII that understand war as continuous and pervasive. But the temporalities of Warlight also attest to the affective experience of being suspended between the war’ s closure and its reanimation. This is why Nathaniel seems to remain in arrested development despite his arduous yearning for futurity, for filling in and overcoming the silences of his life. Even though by the novel’ s conclusion Nathaniel ascertains much about his mother’ s life, as well as the actual identities of the guardians who raised him, his comprehension remains partial, testifying to the impossibility of memoir, which he had early on acknowledged as not “a reliving, but a rewitnessing.” The idea of rewitnessing suggests that one does not so much inhabit the past as simply acknowledge it as always received through degrees of mediation. In the final pages of the novel, Nathaniel further develops this idea by declaring, “We order our lives with barely held stories. ” The act of barely holding something evokes the senseof tenuousness that Nathaniel cannot dispel when trying to comprehend his life in the midst of war’ s ongoingness. If Ondaatje means to provide a denouement to the bildungsroman of Nathaniel’ s life, then it is nothing more than this affirmation of incompleteness.

Naeem Mohaiemen, Two Meetings and a Funeral

Reviewed by Eli Rudavsky

La Coupole d’Alger Arena, still from Two Meetings and a Funeral.

I.

In a ballroom in the Palais de Nation in Algeria, men remove shrouds from the tables and chairs. It’s as if they are unveiling antiques for an estate sale, or uncovering a corpse. Perhaps they are restoring the room to its original state, so that we see how it looked during the fourth conference of the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) in 1973. But really, why are they dusting off a forgotten building, and why are we now looking at a place and time long gone? The question remains unanswered for now—Naeem Mohaeimen’s camera floats through the room, sweeps past the men’s shoulders, and turns down a long corridor, leaving the men behind.

In Two Meetings and a Funeral, a three-channel film that Mohaiemen made in 2017 on commission from Documenta 14, the camera navigates space with a precision whose aim is wonder. As the camera stalks the curved exterior of La Coupole d’Alger Arena, we feel as if we are exploring a new planet or surveying the ruins of a lost one. Designed by Oscar Neimeyer and completed in 1975, the giant indoor sports complex is majestic even in its neglect.

The historian Vijay Prashad, who guides much of the film, walks alone onto the central court of the arena, which is painted in solid colors and demarcated by curved white lines. The gigantic La Coupole d’Alger Arena had once intended, perhaps, to project the power of Algeria’s post-colonial order, and its commitment to radical democratic inclusion. “Just like the Mayan ruins look like they came from outer space, so do these ruins,” he says. “They produced these giant buildings, they’re so hard to maintain, they looked shabby perhaps days after they finished constructing it…How were you supposed to maintain something so enormous?”

Prashad could just as well be asking about NAM itself. Created in 1961, NAM comprised a wave of developing countries emerging from imperialism, united to forge a path forward independent of US or Soviet influence.

NAM was fueled by the common struggle and successes of its member nations in the fight against colonialism. At the Bandung Conference in 1955—a meeting of African and Asian countries that helped lay the groundwork for NAM—Indonesia’s president Sukarno gave voice to the charged moment:

Irresistible forces have swept the two continents. The mental, spiritual and political face of the whole world has been changed and the process is still not complete. There are new conditions, new concepts, new problems, new ideals abroad in the world. Hurricanes of national awakening and reawakening have swept over the land, shaking it, changing it, changing it for the better. [1]

At NAM’s meetings, this feeling was molded into common principles and purposes. NAM advocated a radical shift away from its member countries’ colonial past, demanding “the redistribution of the world’s resources, a more dignified rate of return for the labor power of their people, and a shared acknowledgement of the heritage of science, technology, and culture.”[2]

Muammar Gaddafi, still from Two Meetings and a Funeral.

However, NAM’s spirited period was short-lived; though it flourished in the 1960s, the Movement soon began to unravel, splintering into more powerful orders. In The Darker Nations: A People’s History of the Third World, Vijay Prashad argues that the “Third World project came with a built-in flaw”[3]—the fight for national independence in former colonies required a unity across class and political order that proved brittle after independence was achieved. Once the colonial powers were uprooted, a complex reality came into being in the newly sovereign states. Former social hierarchies reestablished themselves and the class of elites that had ruled before independence reasserted their control.

Early on, pressure from the working classes and the lasting spirit of national liberation tempered political elites. But by the 1970s, the ruling class “compromise ideology…that combined the promise of equality with the maintenance of social hierarchy” was broken.[4] The people suffered a shortage of basic needs, and war and corruption begat economic crisis. Newly independent nations were encouraged to borrow capital at disadvantageous rates, and were soon pushed into default. In exchange for rolling over their debt, the International Monetary Fund demanded that their governments agree to neoliberal structural adjustments, including welfare cuts and the privatization of industry. These changes only twisted the dagger further into the heart of the Third World project:

The assassination of the Third World led to the desiccation of the capacity of the state to act on behalf of the population, an end to making the case for a new international economic order, and a disavowal of the goals of socialism. Dominant classes that had once been tethered to the Third World agenda now cut loose…An upshot of this demise of the Third World agenda was the growth of forms of cultural nationalism in the darker nations…Fundamentalist religion, race, and unreconstructed forms of class power emerged from under the wreckage.[5]

Mohaiemen charts these shifting waters in Two Meetings and a Funeral . His film is projected onto three screens side by side. In one sequence, he uses brief messages to describe how Western influence, global capitalism, and fundamentalist religion washed the Third World project away over time, and then took its place; on one screen is a title, another the year, and on the third an event:

Season of Tigers. 1975. Bangladesh’s president and family murdered in Islamist-allied coup, with alleged CIA backing. Pakistan and Saudi Arabia first to recognize new military regime in Bangladesh. 1977. As his Socialist alliance collapses, Pakistan’s Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto overthrown in CIA-backed coup. / Funeral Pyre. 1982. Bangladesh chosen as host for Nonaligned summit, starts building conference center. 1990. Nonaligned summit postponed…2013. Bangabandhu Center available to rent for events, celebrations, and trade fairs.

II.

Two Meetings and a Funeral considers how the buildings in NAM’s orbit bear history. The colossal structures that Vijay Prashad visits seem out of place, their motivating ideology abandoned. Rows of catalogue drawers at the United Nations once filled with information are now neat and hollow, and buildings like the Bangabandhu International Conference Center and the Palais de Nation are used for commercial purposes or visited as historical relics. It is uncanny to look at places designed to elevate meetings of great purpose now sitting lifeless.

How did we get here?

In conversation with Prashad, the archaeologist and writer Samia Zennadi reflects on the transformation Algeria has undergone since the era in which NAM thrived. For her generation, who lived through the charged period of anti-colonial struggle, it is now as if the ground has fallen from under their feet. Where did the Movement go? Its language remains, but the world looks so different. The older generation is split off from the younger one.

Mohaiemen’s film is split into three channels. Like the delegates of NAM—who saw their colleagues speak at the podium, but who understood their words by translation in their headsets—the audience of Two Meetings and a Funeral experiences a similar dissociation of image and language. The image of the speaker appears on one screen, and their words appear in English on another. Mohaiemen literally shapes and colors his subjects’ words, transforming them from subtitles into symbols. Language is spectacle in the NAM conferences, and in the present Algerian political discourse that Zennadi describes—so too in Mohaiemen’s film.

Still from Two Meetings and a Funeral.

Zennadi points to language as an example of the stunted political discourse in Algeria. “[I]n the 1970s Algeria was a nation of Africans. Sub-Saharan Africans were present in literature, cinema, theater. But now things have dissolved into nonsense, a void. And what’s left? Yes, we still chant “Pan-Africanism.” But…[y]ou often hear Algerians say: ‘We’ve never been to Africa.’ They forget we’re on African land.”

Two Meetings and a Funeral inquires about the nature of residue. What do we make of linguistic or physical structures when they have been emptied out? When language and architecture that once burst forth with a popular anti-imperialist movement in Bangladesh, or Algeria, are now empty, or swelling with capitalist enterprise?

At the end of the film, Vijay Prashad muses that the film might bridge the gap between the old generation of NAM that built a vigorous liberation movement, and the young generation that knows little of it. And maybe it will. However, the first aim of Mohaiemen’s film is not to bridge any gap, but instead to look closely at the residue of a movement that has practically died.

Perhaps in the ballroom in the Palais de Nation, under a chair or behind a curtain, the men cleaning will find something left behind from the fourth conference of NAM. Or, in footage of Fidel Castro applauding Arafat at the 4th NAM conference, in the curve of La Coupole D’Alger Arena, we might suddenly catch the glimmer of life that animated the Third World project. In Two Meetings and a Funeral, Naeem Mohaiemen trains his eye on the drama and spectacle of history, its unexpected twists and moments of personal grace. In so doing, he draws us closer to the embers of the Third World project and asks us what it would mean to kindle them again.

Notes:

[1] Vijay Prashad,The Darker Nations: A People’s History of the Third World (The New Press: New York, 2007), p.33.

[2] Ibid., xvii.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid., xviii.

Samiya Bashir, Field Theories

Reviewed by Kirsten (Kai) Ihns

In physics, field theory is a way of accounting for physical phenomena in terms of a field (where a field describes a space governed by a delimited set of rules and forces) and the interactions among fields and with matter. In Samiya Bashir’s Field Theories, the theories, and the fields they reach for, include not only the magnetic, gravitational, and electrical fields one might expect, but also America’s troubled racial history thought as a field, fields of influence, fields of human relation. Bashir thinks all these terms through each other and, by recasting lived experience in the terms of physics and physics in the form of the material details of human life, opens new ways of thinking about each.

One of the primary ways Bashir produces this recasting is her titling scheme—many of the poems have titles that use physics terminology and concepts. The book is broken into roughly eight sections, each headed by a quote from a prominent Black public figure, overlaid on a grayed-out and tilted version of the Planck equation in the background. The sections follow a kind of countdown through the laws of thermodynamics, from “Consequences of the laws of thermodynamics” to “Zeroth law,” punctuated by three historical persona-poem sections all titled “CORONAGRAPHY.” The poems in each of the sections have loose but traceable relationships to the physics concepts from which they take their names—the poem called “Second law,” for instance, deals with the frictions and losses of force that come with time, labor, and difficult love relationships, “spent matches with burnt-out / love —,” “print / disappearing disappearing.” The second law of thermodynamics dictates that changes in entropy of a given system can never be negative; systems tend to move toward increased disorder over time. Other representative titles include “Carnot cycle,” “Planck’s constant,” and “Radio ∴ Wave,” a poem interested in traversing time and space (“across the road”; “sail”; “roamed”; “nomads”) and whose references range from “black holes” and sailable “starlight winds” to “Eocene camels,” “damp desert nomads,” and “the radio.” Like the radio waves (and radio and waves) of the title, the poem’s thought travels freely, invisible but consistent in its frequency and the choreography of its stanzaic patterning (consistently three lines, which gently get longer as the poem continues).

Bashir’s graceful and idiosyncratic rhythmic and sonic sensibilities are part of what makes the poems energetic and a pleasure to read—they’re a study in high craft done with a light touch. Though it’s difficult to locate how Bashir does it exactly, I would say some of her major tools are heavily enjambed, short, spare stanzas (frequently couplets) and a consistent use of near rhymes, assonance, and consonance punctuated by moments of heightened sonic density. The degree to which the poems draw attention to their own sonic crafted-ness feels thoughtfully modulated throughout both individual poems and the book, and is part of what produces a feeling of effortlessness and grace. Bashir doesn’t do what many poets invested in craft do, which is to say, she doesn’t constantly insist that we notice that work is being done formally. I’ll point out two examples that help clarify, but mostly one gets a sense of this effect by moving through longer sections of the book. The first example is from one of the last poems in the book, “Zeroth law,” named for the thermodynamics principle that specifies that relations of thermal equilibrium work transitively. If A is in equilibrium with B, and B is in equilibrium with C, A is in equilibrium with C. The poem, similarly, uses a kind of 2–3 modulation in its sonic patterning. I quote the entire poem here to exemplify Bashir’s craft and also because I think it’s such a beautiful poem:

When leaning on the backyard beam

beneath a full wolf moon and my slippers

shiver under my nightdress as I happen

upon a reason for waking call it a snowflake

a belly-flop blue jay or even my own small toe

peeking through a not-yet-hole as it fissures into

my slipper’s future and I’m not out for a jog or

to find a misplaced piece of scoundrel lover

but to marry my morning coffee to

an old cigarette to the new blue-gray light

of an icy pacific year in mid-set

See how they swinghold hands and raise the sun?

Hey, you! Bluebird! Whatever will we do

— exhale — with all of these merciful gifts?

Often, two words sharing a vowel sound (e.g., “leaning” and “beam” in the first line) will occur close together, and then a later section of the poem will repeat this sound (e.g., “beneath” as the turnaround word in the second line), chiming across the poem’s lines and stanzas. Similarly, the first stanza ends with a strongly emphasized “-ake” sound: “upon a reason for waking call it a snowflake,” which the next stanza picks up as an echo in the long “a” in the “jay” of “belly-flop blue jay”—“jay” heard loudly because it works as a kind of landing place after the three modifiers preceding it. The effect of this is a smoothly transitive linkage—we hear the linkage of “leaning” and “beneath” across the line break, like two systems in equilibrium with each other through their relation to a middle system. Similarly, you can hear the linkage of “waking” and “jay” across the stanza break, sustained in their relation by the shared middle term. Also, like “belly-flop blue jay,” in this poem (as elsewhere in the book), Bashir will often formulate highly compounded nouns—“misplaced piece of scoundrel lover,” “new blue-gray light,” “a not-yet-hole,” “icy pacific year”—which have an effect similar to Hopkins’s sprung rhythm and concentration of stress (e.g., “dapple-dawn-drawn Falcon”). They function like prosodic intensifiers, which Bashir balances with smoothed, lower-stress regions around them. The effect is what might be called an elegant rollicking, as paradoxical as that might seem. It’s a rhythmic intensity that is unpredictable, resistant to monotony, a pleasure to think with. Bashir cites great blues and jazz artists and critics in the poems, and it’s of course hard not to place her work in relation to theirs, and perhaps also in relation to Charles Olson’s notion of Projective Verse and field poetics—by attending to the rhythms of breath, and engaging speech where it is “least careless—and least logical.” Bashir finds an intuitive and energetic way through the poems.

Bashir also develops rich networks of consonantal patterning. Briefly tracking how they work can help draw out some of the ways one can see “fields” operating formally in her poems. Here’s the ending from “Planck’s constant”:

the sun went down forever so

what else made sense but to

climb one another hand over

hand and cleave to whoever was

left and near enough and would?

The couplets are very comfortable with leaving dangling connective words (“so,” “to,” “over,” “was”) at the ends of their lines and with delaying closure of the sense unit to the next couplet, which, combined with the internal sonic balance of the lines, produces a kind of forceful but casual propulsion from couplet to couplet. Also important here are the subtle and nested consonantal and vowel patterns—there is a remarkably high frequency of words that use “ve” (“forever,” “over,” “cleave,” “whoever”) and each of these words also participates in networks of vowel patterns happening in the section. These networks make the “ve” words feel like nodes where patterns or fields, if you will, intersect, lifting them higher in the reader’s attention—there are a lot of long “o” sounds in relational words (“over,” “so,” “who,” “to”) that draw them together, and many short “e” sounds as well (“left,” “sense,” “-ever,” “enough,” “else,” “went”). And though these sounds are common enough, their repetitive occurrence here, in ways that circulate around the less common “ve” words, produces a fluid but perceptible field—a space defined by delimited rules, a space where movement is possible. I think this ending is so satisfying and effective (as many of Bashir’s endings are) partially because its last line, allowing for a “headless” catalectic first foot, also crystallizes a ghostly iambic patterning that floats around elsewhere in the poem—“__left | and near | enough | and would”—the line falling into iambic tetrameter. The effect is at once one of closure, as the pattern rises to the threshold of perceptibility, and also springing-forward—iambic tetrameter being often the energetic meter of children’s rhymes and 4/4 song lyrics.

The last line also asks for a flexibility of sense-making that produces a kind of pleasing intellectual swiveling (also something Bashir does well), which I think is available to experience as itself a kind of motion. Specifically, I refer to the lines “cleave to whoever was / left and near enough and would”: in this formulation, “left,” “near enough,” and “would” all ask to be read as modifiers of “whoever.” But they are quite different words, both in the implied relation they produce between the “whoever” and the world, and in the degree to which they resist their grammatical status as modifiers. Whoever “was left” suggests that the participation of “whoever” in the cleaving is the result of the world’s action (“whoever was left” suggests simply a state of affairs—the existence of the whoever is a marker of what has happened in the world). “Near enough” suggests relational placed-ness; “whoever” may be identified based on their position (in a field of action) relative to the speaker; we think their identity relationally. And then, finally, “would”—here the “whoever” is summoned as an agent, they may be identified based on their inclination. But the formulation places all these terms on equal footing, forcing the reader to encounter them in the same framing and to think quite differently in order to make sense of each of them. In so doing, the line seems to point to the fact that the action of sense-making might really be described as understanding the relational field produced or suggested by the behavior of the terms within it. The friction between the identical framing and the kind of sense-making each word asks of the reader makes the fields of the poem’s form perceptible. That’s to say, it helps to show, at a granular, formal level, the complex ways one can project relation through language, and how the “world” and/or the “I,” can swivel into and out of place as the frame of reference, the field of orientation.

In addition to enriching the ways one can think about human experience under the sign of physics, one of Bashir’s major projects in this book is to think about how race, and the ways Western colonialism and capitalism have operated to produce and then to exploit race, affect the daily lived experience of Black people. History and race, in other words, are also fields for theorizing here. For example, “Law of total probability” notes—through a text riddled with white holes (blank circular spaces that partially obscure the words—perhaps recalling the scattering and reflective “white bodies” of physics)—that “i cross the street away from cops of / my being black.” The “CORONAGRAPHY” series represents two lovers struggling under slavery, with the term “slavery” louder for being unspoken, as one covers the sun in a coronagraph to be able to see the fainter light at the edges. Or consider the ways the texts ask the reader to hear or perceive the human “Black body” in poem titles like “Blackbody curve” (a physics term having to do with the amount of radiation emitted by a black body, in physics an ideally absorptive entity from which no radiation escapes). Field Theories makes its reader think about their own position in these fields, and how that position affects their possibilities of relation to the text. For example, about midway through the book, a poem called “You don’t have to pump the breaks you just gotta keep your eyes on the road”—possibly referring to the 1980 South African Apartheid-era film The Gods Must Be Crazy—describes the nonchalant cruelty of “white people”:

Coke bottles falling from the sky to

an old man’s village and the white people just

laugh and laugh and line up to pay and laugh

and get paid and laugh. That’s what they made.

Just a few stanzas later, a “we” (i.e., not the “white people” of the above-quoted stanza) emerges, a “we” that becomes increasingly present in the second half of the book. While Field Theories engages throughout with issues of race, it is at this moment that it seems to ask the reader most directly to think about the ways race and racism and history impact life not only in the abstract, but to think about where they situate themselves within these fields, to identify their own position in the field because, as the previously quoted ending of “Planck’s Constant” shows, it is only in terms of the field that one can be in relation. More directly, the racially marked “we” here necessitates reflection on the politics of identification—can you identify with or operate within the “we,” itself a kind of space or field?

What makes this work particularly remarkable and interesting is the way that, even as the poems demand that you reflect on and identify your own position (one possibly outside the first-person plural position they mark for themselves) they allow a movement-alongside and sustain a relation, one whose terms include an awareness of the multiple kinds of fields the poems work to make perceptible. You just have to stand, as a body, aware of the terms of the fields acting on you, to do so. Overall Bashir’s book is beautiful, thoughtful, graceful, and strange. It is a book that makes the conditions of sense-making, the conditions of life in a system with an inherited racist history, the conditions of formal movement in a poem, available to sense in new ways.

This review is in Chicago Review 62:4/63:1/2.

Daniel Owen, Restaurant Samsara

Reviewed by Sotère Torregian

“Something Happens Under the Bridge”: Three Recent Books by Gay Trans Men

We Both Laughed in Pleasure: The Selected Diaries of Lou Sullivan, edited by Ellis Martin and Zach Ozma

Zach Ozma, Black Dog Drinking from an Outdoor Pool

Oliver Baez Bendorf, Advantages of Being Evergreen

Reviewed by Gabriel Ojeda-Sagué

The marble ass that covers the new publication of the diaries of Lou Sullivan, the gay and trans activist and writer who passed away from AIDS complications in 1991, is a useful hint at the person we are about to meet within the book’s pages. Sullivan is the definition of boy-crazy. From his beginnings as a young Christian child ravenously obsessed with the Beatles (“Paul-Ringo-Paul-Ringo they keep bouncing around my head. They’re so perfect […] This is a love so strong and real. Oh, love me, too, anyone”) to the adult cruising San Francisco’s leather bars, Sullivan writes with awe about men and the love men might share. “The beauty of a man loving a man just takes away my breath,” he writes in a late entry.

As hinted by its title, We Both Laughed in Pleasure: The Selected Diaries of Lou Sullivan is a deeply erotic book. Sullivan’s diaries record in great detail his sexual exploits, romantic infatuations, and complex personal relationships. These reminiscences are written in a style somewhere between childlike giddiness and deft description, where you can sense that Sullivan is turning himself on with every entry he writes. His life and diary are committed to gay sex, seeing in it the embodiment of the challenge and passion of life at the margins. “What has it been about male / male love that has made me desire it so?” Sullivan asks himself in a late entry, “the fact that it didn’t happen—that the two people involved really wanted to be with each other, and that the other person chose to love him […] despite all forces against them, they clung to each other with desire.”

But the sex Sullivan records in these pages is not always so affirming and so brave as he idealizes gay sex to be. Though Sullivan often describes sex as a useful tool towards learning truths about his own manhood, the reader is made painfully aware (more aware, it seems, than Sullivan was at times) of the way sex becomes an obstacle to Sullivan’s becoming. His lovers, especially the “T” who is the last major relationship of his life, often use sex as an arena to debate Sullivan’s transition and to propose certain ideas about how he should embody his gender. It is often saddening and frustrating to read the ways Sullivan’s lovers leverage their own sexual identities against his still-blossoming gender identity, or to read his lovers using sexual pleasure against his plans for transition, as when he writes “[T] said I shouldn’t get the cock operation because I am enjoying my pussy. I agreed and told him what a special person he is.”

This selection of journal entries, which Sullivan always imagined being published, makes for an essential record of the daily frustrations and pleasures of coming into a sense of self. Importantly, it is a useful record of a scene (specifically, 70s and 80s queer San Francisco, both its activist networks and its sexual ones) and a record of how an individual came to understand themselves as an individual within a scene. But at the moment when Sullivan finally holds the most crystal-clear sense of himself, he is diagnosed with HIV. Sullivan has said both in the diaries and in public interviews that his greatest sadness upon diagnosis was fear that his bottom surgery (begun, but not healed properly, in 1986 before diagnosis) would never be fully finished and corrected, as he feared doctors would be unwilling to do surgery on him.

In a book textured by humor, pleasure, ecstasy, giddiness, and sadness, this “final chapter” is obviously dominated by pain. Though his always charming and funny style remains surprisingly present, there is a clear loss of energy and life excitement in this last section, as Sullivan details some of his medical routines, new difficulties, and friends’ deaths. But, at the very least, Sullivan dies having definitively answered major questions about himself that have been puzzled over for the hundreds of pages that make up this selection. He dies, to use his own terms, “finally a MAN!” having fought long and hard for a place in the gay community he has admired since he was a child. It is perhaps this knowledge that lets him write, with characteristic goofiness:

I heard this remark on television tonight and thought it so appropriate, I wish I’d have thought of it myself back in the olden days, when Dad used to ask me, “What’s it all about?” The answer:

You do the hokey-pokey

And you turn yourself around

That’s what it’s all about…

Susan Stryker, in her heartfelt introduction to the selection, is exactly right when she says, “get ready to meet a great soul.” That’s what this book feels like, an opportunity to meet someone great. The sleek editing work by Ellis Martin and Zach Ozma, the campy but handsome design by Joel Gregory, and the joint publishing work of Nightboat Books and the now-departed Timeless, Infinite Light, together make that meeting both possible and deeply pleasurable.

We Both Laughed in Pleasure is only half the reason why its co-editor Zach Ozma is having a good year. 2019 has also brought the release of his debut poetry book Black Dog Drinking from an Outdoor Pool, a semi-autobiographical coming-of-age narrative told in verse through a small group of characters named simply by their roles: “mother,” “father,” “dog,” “boy,” and “i.” Its language is plain and quietly sad, with moments of evocative tension. For these reasons and others, the book’s most obvious ancestor is The Book of Frank (2009) by CA Conrad. Readers familiar with The Book of Frank will recognize its precise mix of melancholy, desire, repulsion, and wonder in Ozma’s poems such as “Garbage Man”:

father accuses mother of an affair with the garbage man

but it’s dog that licks the slime from between

the trash collector’s wicked fingers

Ozma shares with Conrad an ability to make every ingredient of a scene feel confoundingly meaningful, communicative in ways that unsettle rather than answer questions. It’s an ability that makes the formal simplicity of the lines in this queer biography feel resplendent, as Conrad’s sparse free verse did in The Book of Frank.

The narrative seems to tell us how an “i” comes into selfhood in an upbringing with a difficult, distant, and hard-to-read father, and in the aftermath of that father’s suicide. The “dog” overlaps with several of the character’s embodiments, working as a particularly mobile image and emotional site. We get scenes where father becomes dog (“father licks himself clean / father curls up by fire / father crawls under house to die”), or scenes where the “i” becomes dog (“it leaves soft impressions in my fur”). The “dog” might be the comforting companion during grief, or the lived, furry embodiment of grief’s complexity.

In a series of puns on the phrase “good boy,” the “i” and the dog are in some form of allegiance, the phrase marking a category they would both like to belong to, sometimes even do. Becoming “dog” is mapped onto become “man/boy,” so that the struggle over the image of the dog that organizes this book is based in the fact that “father” represents a “garbage man” and a “bad dog” (“we lied and said father doesn’t bite”), while the “i” is struggling to fit into being a “good boy.” But even as I say that, I am aware that there is a kind of stretchiness to the images struggled over in this book, and that such a reading fails to account for all of the textures “dog,” “father,” “boy,” and “i” take up.

Through all this stretchiness, it is clear that Black Dog Drinking from an Outdoor Pool is a book about death as an instance for becoming, where becoming might mean something like animalization. Its pages are peppered with transformations:

father’s dog died when i was born

house too small for many pups

dog curled up in mud

became a redwood

i curled up in low pile carpet

became a boy

Without making any guesses as to the timeline of the editing of We Both Laughed in Pleasure and the writing of Black Dog Drinking from an Outdoor Pool, it seems to me that Ozma either learned from or appreciates Sullivan’s critical attention to the way events, especially sex and death, catalyze or frustrate the process of personal becoming. While Sullivan’s book is a record of the ordinary, a record of his becoming over time, Ozma’s is a bestiary of the ordinary, somewhere between fairy tale and memoir.

Animalization, becoming, and death as a set of questions for trans life is a problem set encountered in another 2019 poetry collection. Oliver Baez Bendorf’s Advantages of Being Evergreen is a brief collection of woodsy lyrics published by the Cleveland State University Poetry Center. The book’s central concern seems to be the difficult task of imagining sanctuary for a body heavy with memory, catalyzed into change, and charged with desire:

Earth not even buried

in the earth. So many gay

bodies on fire, offerings to

gods who don’t deserve us,

gods of punishment, gods of plight.

The land in the holler weeps.

Still we dream of sanctuary,

follow a hand-drawn map

up the mountain.

On the quest to “put on a self,” the speaker in Advantages of Being Evergreen takes a deep dive into the ecosystem, looking to nature for a model of self both wild and preservable. Its style is primarily in-line with the contemporary lyric styles that CSUPC has published in recent years, though the book is also populated by some experiments in form. In its sound and its images the book strives for consonance over dissonance, though always upholding “wildness” as a form for life. Baez Bendorf writes: “I inject, grow a beard, bleed a while… I become my wildest self / through make-believe—to the river with this thunderous me[…].”

Rainwater, the river, foxes, and bears all repeatedly appear in these poems in the context of grief, transition, queerness, their presence received with something akin to awe or desirous curiosity. The river is the star of one of the collection’s most impressive poems “River I Dream About.” The poem is a repetitive structure of fragments using the word “river” (“River that curve down a backbone./River through which I particle heat.”), sharing an interest with a few other poems in the collection in a more procedural, patterned, and mechanical language. But the poem, as it continues, breaks its form with the I’s transition to the sentence’s subject, moving away from phrases like “River I dream about” to something like the poem’s final lines: “I will be there, printing textures of rock / on the skin of me, belly down, face down. / My god it is good to be home.” What starts as a kind of scenic and recurrent exploration of a variety of rivers is slowly made into a home by the appearance and the movement of the I within the network of rivers. What the poem slowly builds with this grammatical shift is a sense of belonging, the feeling of one’s body belonging in an environment, and the feeling that one’s body belongs to oneself, wild or otherwise: “river where/my fur belongs to me.”

I recall Lou Sullivan’s journals when reading the closing lines from Baez Bendorf in another standout poem “Who Spit into the Pumpkin, Who They Waiting For”: “What I want from the river is what I always want: / to be held by a stronger thing that, in the end, chooses mercy.” It is the sensitive portrayal of gay desire’s risky tenderness that seems shared between Baez Bendorf and Sullivan. I mean by that both the feeling of the love existing “despite all forces,” to use Sullivan’s words of worship, and the danger always associated with the act of loving men. The erotics in Advantages of Being Evergreen are relatively subtle and smartly written, even when they seem to be the innocent and clumsy desires of summer camp and the wilderness. Gay writing has always been obsessed with how to precisely catch and describe our desires, especially the love and sex that moves through the summer heat. In this ongoing debate, Baez Bendorf has landed somewhere productive. “something happens under the bridge. I come up singing,” he writes in “Who Spit into the Pumpkin, Who They Waiting For.” “something” might be a personal transformation, an interpersonal act of desire, an interpersonal act of violence, or something more mundane, the ambiguity capturing some of the subtle but uncensored description of gay desire. The line’s placement in the middle of a nearly-prosaic stanza makes its central transformation, its “something” that “happens,” feel ordinary, as much a part of the landscape as the eggs, hens, peppers, marjoram, and pumpkin that surround it.

In the connection between desire, the animal, the natural, and trans life, Advantages of Being Evergreen—along with recent books like Ozma’s collection, Chely Lima’s 2017 What the Werewolf Told Them, CA Conrad’s 2014 ECODEVIANCE, and The Criminal: Invisibility of Parallel Forces by Max Wolf Valerio—is not exactly unprecedented. But in Baez Bendorf’s version, this thematic connection is staged, perhaps deceptively, as the connection of all things. He writes of a kind of congregation of “everything under the moon” in a form of relation that is pleasurable, mysterious, and productive. The book’s finish occurs in the great ecstasy of this congregation: “the earth is my home and there is / much to cry about. It always helps / to look up, look all the way up // look up, look up, look up, we look / up, up, up.” The repeated words, along with the mapping of earth/heavens along issues of sanctuary, makes this conclusion the most explicit revelation of the book’s aesthetics of the spiritual.

Baez Bendorf’s book is aesthetically and thematically working over the issue of belonging, a theme Sullivan mapped constantly in journal entries throughout his life. Sullivan felt, by turns, an unprecedented sense of belonging and a confounding sense of exclusion amongst his scene of San Francisco queers. He worshipped gay men’s love, of which he endlessly desired to become a part, but was often reminded (by lovers, by friends) of his difference from the cis gay men that he gave so much care to. The writings of Sullivan, an ancestor for all of contemporary queer community, but especially for trans gay men, clearly offer a set of tools, anxieties, dreams, and desires to the many trans gay talents writing now: Ozma, Baez Bendorf, Stephen Ira, Ely Shipley, Jay Besemer, Ari Banias, to name only a limited few in poetry. In these publication’s coinciding in 2019, this lineage is made resplendently clear.

October 2019

Nikki Wallschlaeger, Crawlspace

Reviewed by Jose-Luis Moctezuma

The history of the sonnet is, among many things, a history of a composure derailed at an alarming moment of epiphany. Despite the message being trammeled in fourteen lines, or in the period-specific coding of its medium, the sonnet’ s epiphany is based less in the form than in the activation that the form engineers. In the Petrarchan tradition, the sonnet is a dichotomous structure that plays on a balancing of inequalities; in the Shakespearean, it terminates in a couplet that ties together divorced rhymes at its endpoint like strings bridging the tongue of a shoe. In Nikki Wallschlaeger’ s Crawlspace, a book composed of fifty-five sonnets (some unnumbered, some missing), the sonnet is none of these things, nor does it care to be. Instead, the function, divorced of its form, is approached from an angle of vision that disrupts the sonnet’ s usual allegiances and skillfully deconstructs its historical baggage. Here, the sonnet is nothing more, nothing less, than an unlocked room, a deterritorialized space in which extraordinary incidents and minor violences might occur, or have already happened, if you look closely enough. As Wallschlaeger writes in “Sonnet (3) ”: “What is the difference between / a house and a mall really? ” A critical difference that points at the deleterious effects of a metastasized capitalism, in which human interiority becomes perilously entwined with corporate sprawl: “You and your family can live here / pay rent and/or mortgage. ” The tenancy, in this case, is the fraught real estate of the sonnet space.

Wallschlaeger’ s incredible technique blueprints the sonnet’ s fourteen-line structure in several formally innovative ways, some lines longer and laden with decolonial insight, others breaking off toward alternate freedoms, to reveal startling lacunae or risky omissions in a rhetoric of United Statesian pathos. As such, Crawlspace should be considered a new entry in the tradition of anti-sonnets, along the lines of Ted Berrigan’ s, Bernadette Mayer’ s, and Clark Coolidge’ s postmodern sonneteering and, most recently, in the work of Sandra Simonds, Ian Heames, and Terrence Hayes, which powerfully redefines what the sonnet can assemble and do. In disassembling the form, Crawlspace goes further in interrogating and reconstructing the constrictions of a tradition complicit with what Wallschlaeger calls “the constraints of your oppressors.”

Part of the beauty of Wallschlaeger’ s intervention in the history of a form is its construction of an unhistory, a turning-upside-down of a vessel that spills out the contents of an occluded discontent. In “Sonnet (8), ” she writes that “we should all be oyster joyous & keyless / when we have our geometries managed / & the intersections waiting on tables / showing us how to be better at patience. ” In the widening gap between labor classes and derivative classes, and in the racialization that ensues, the career ambitions of everyday people are reduced to waiting for tips and promotion in the service industry, and it is in service to the crude reductions of capital’ s “layers & layers of prison care ” that negativity is flipped (obscenely) into positivity. Wealth is whited out and wiled away, while silence and complicity are malignantly posited as a virtue: “we are going to be abundantly / pleasant & quiet on a payday afternoon. ” There are no persons or personalities here (not even personae): instead, personhoods, disconnected voices, instructions, and actions default or finish in irremediable frustrations. The joys are minor but consumerist: “My joy, privately owned. ” Pointing her weapon at the sonnet’ s cagey form, carceral capitalism rears its head: “The most crafted ending of all / is usually the electric fence. ”

Ultimately, part of Wallschlaeger’ s critique is about whiteness and its heralds, the historical investiture of prosodic form. Colonialist paragons are incinerated into blurs of white sameness: “George Washington’ s mouth comin at you / yappin some bullshit about honesty or was / that Abe Lincoln I dunno they start to fade. ” What Claude McKay had queried of the nation’ s “tiger’ s tooth ” sunk into his throat in the sonnet “America, ” Wallschlaeger pursues in her navigations “about White Satan & the reign of Ira Glass ”:

No boudoir photo in this country

could convince me

that America is the best place

to fuck. Cities sprouting

out of my skin & I tug

at your famous teenage welts.

Wallschlaeger’ s polemic is a necessary one, charged by a deep knowledge of the hazards of whiteness in everyday life. Whiteness isn’ t (just) a person, a politics, or a color (the terrifying “visible absence of color, ” as Melville says), but it’ s also the invisible flag bearing the arms of the capitalist mechanism, the ideological whiteout that displaces difference and remarks on it in the same manner that people shopping at Target remark on the linen count in a bedding package or the argyle design in a cheaply and brutally manufactured cardigan imported from Sri Lanka. Whether a skin for the phone, or a template for the small business website, the whiteness of everyday life creates a crawlspace for the bifurcated, disaffected mind.

More importantly, whiteness is a zone of tensions and resistances where personal history becomes dangerously imbricated with colonialist, corny-as-fuck, hegemonic forms of thinking, which Wallschlaeger is asked, often forced, to adopt:

When I hurt I think about

the racism of my white mother in rearview mirrors,

who suggested I read The Color of Water & believed

in the joy of Hattie’ s enslavement & how because

of this I keep my blackgirl magic protected protected

their souvenirs from this nostalgic scene: a brunette

on perky roller skates pumping up the muzak gaslight,

decorative plate ordered from Fingerhut, the iconic ‘50s

inspired Coca-Cola kitchen set.

The everyday detritus of capitalist spectacle covers over the everyday casual racism of cultural assumptions and reconciliation fantasies. If it isn’ t the unspoken, yet heavily policed, codifications of race, it is patriarchy and mansplaining that arrest the speaker in the mire of the sonnet’ s assumptions concerning mastery and voice:

You liked the book I was reading

matched my blouse & said so approvingly.

Girls with portable accessories then a gentle

corrective in the authors I should read next.

I’ m wondering what you have in mind for my

next set of outfits that rhyme with poetry.

The identification here of form with sexism, rhyme with “commercial femininity, ” effectively analogizes the tremendous “Weight grabbed onto/into me ” that Wallschlaeger holds up, tears up, and flings out. Wallschlaeger effectively dismantles the sonnet form, blows it up and distends it to its breaking point, as a way of disputing the tacit linkages between whiteness, patriarchy, and prosodic form. Although this might be interpreted to be an anti-traditional move, Wallschlaeger’ s use of the sonnet as a vehicle of feminist intersectional potential might be related to a long tradition of women poets who have used the sonnet to question male authority and heteronormative desire. As Lisa L. Moore has argued, the sonnet is a space that “often exceeds, reverses, doubles, or even contradicts ” its syntactic and historical lineages because it is in the sonnet’ s “famous doubleness, tension, and sense of internal difference ” that it performs empowerment through subversion and voltaic reflexivity, especially for women and queer poets in the Sapphic tradition. The sonnet, in Wallschaleger’ s hands, contributes to such a tradition, but also complexifies it in the inclusion of intersectional vectors that a sentimentalized (and frequently depoliticized) prosody might leave out.

It is in this spirit that the microaggressions of everyday life (patriarchal, racial, classist) are itemized at the level of the sonnet’ s line-by-line metrical finitude. It isn’ t enough that liberal culture makes room for new and marginal voices in the tradition of a form, but that these voices answer back at the presumed innocence of a “woke ” gentry:

That I’ ve been refused service at diners

in northern Wisconsin so I’ m supposed to be grateful

that you’ re liberal enough to serve me in a restaurant.

[…]

That I’ m nervous now about writing the

line about Los Angeles and New York disappearing

because white supremacy has a way of making folks

disappear.

The secret life of a form might also be the concealed supremacy of a way of thinking, leaving out the exhaust of a burned-up margin only barely discernible in what the history of a form omits or undervalues. That “adding / a black cartoon princess is considered progress ” is what Wallschlaeger wants to unpack and refute: it is not enough to copy or mimic a popular form (the belletristic sonnet as much as a Disneyfication of race relations), there must also be a total derangement of the polite capitalist sensorium. The final “sonnet ” of the book (“Sonnet 55 ”) implements this in a complete and excessive exploding of the sonnet form, extending itself like a wild growth running rampant through a field of carefully pruned flowers and plants, tearing up the ground not through desecration but through more and more growth, more and more sacred rage.

Ultimately, Wallschlaeger exhausts the sonnet form because she is herself exhausted: “I’ ve been exhausted my entire life // I hate telling you / how I really feel. ” Like the impactful Lucille Clifton quote that begins the book (“all of us are tired / and some of us are mad ”), Crawlspace rehearses its conflicts and historical trajectories in a shimmer of intersectional resistance and “blackgirl magic. ” Asking “what of the world’ s municipal mistakes / that are stored in us? ” the book carefully weaves together a picture of the “marked women ” who “transform / ourselves. We are the wood violets & roses stretching in the rain. ” These are not sonnets; they’ re better than that: fiercer, freer, and loosened as the wood violet is of the murky ground. Held, yet uncontained.

This review is in Chicago Review 62:4/63:1/2.

Dawn Lundy Martin, Good Stock Strange Blood

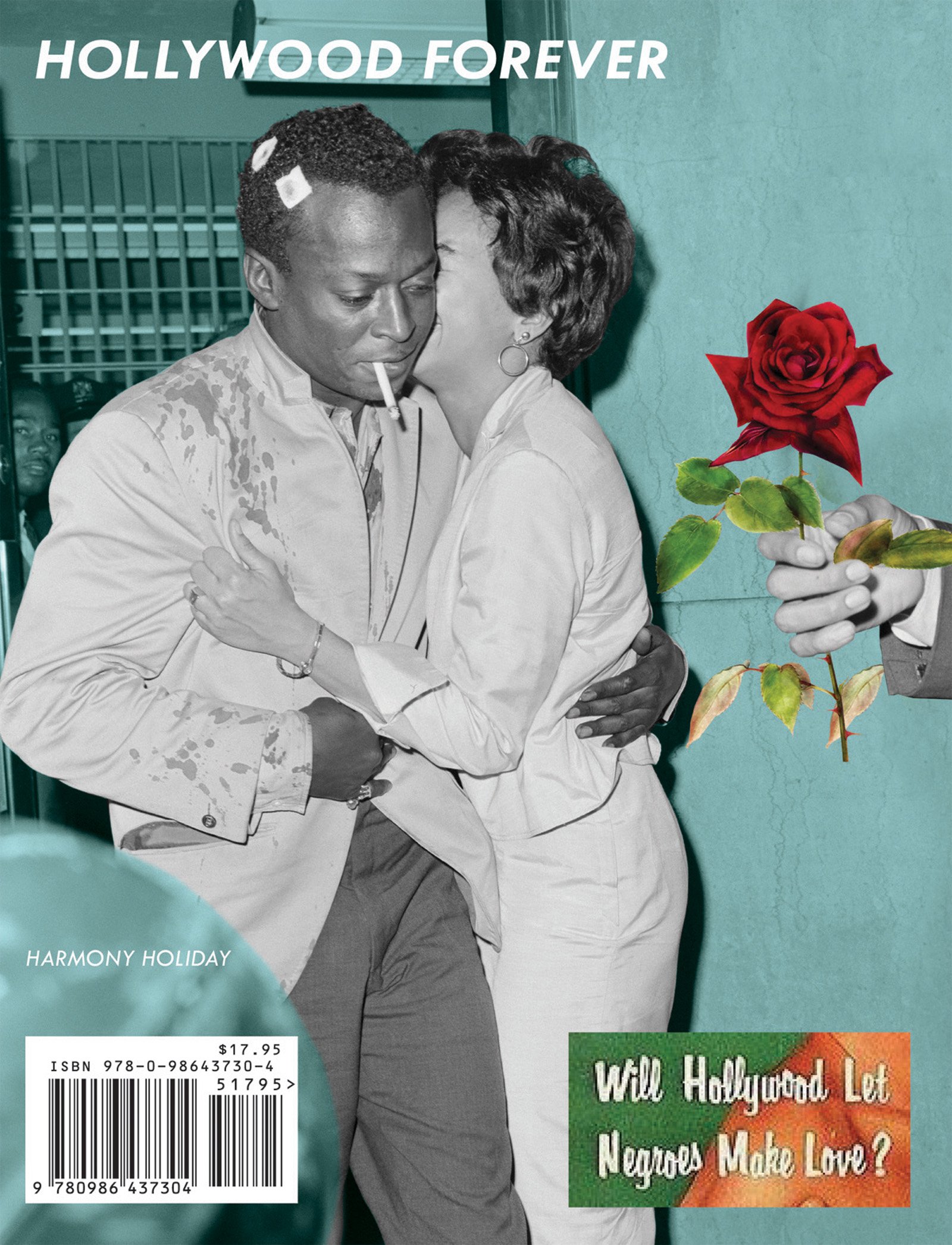

Harmony Holiday, Hollywood Forever

Duriel E. Harris, No Dictionary of a Living Tongue

Reviewed by Tyrone Williams

Based in part on an “experimental libretto ” for a multimedia operatic project that never came to fruition, Dawn Lundy Martin’ s Good Stock Strange Blood explores the conundrum of heritage and choice, what we might summarize as the age-old problem of determinism vis-à-vis the freedom of the will. In this book the drag effect of “history ”—a dystopian resignation to determinism—on Martin’ s fierce utopian drive implies less a tug of war than gothic haunting, the residue of personal and collective trauma. That Black female writers as various as M. NourbeSe Philip, Toni Morrison, Barbara Chase-Riboud, Gayl Jones, Helen Oyeyemi, and Yvonne Vera have also examined the everyday causes and effects of racist violence and patriarchal abuse does not mean Martin’ s writings are to be lightly taken or summarily dismissed. As the emergence of Black Lives Matter and #MeToo attests, Good Stock Strange Blood is old news that remains all too new.

As in her previous collections of poetry, Martin returns to scenes of trauma, to the legacies bequeathed by blood (e.g., light skin and nappy hair moralized as good and bad, respectively) and what we might simply call the “world, ” figured here as boxes within boxes (“When you leave the com- / pound, you discover a larger / compound. You’ re traveling in / the wrong direction”). Since enjambment traditionally functions as both a mode of inertia and mutability—the pleasures of narrative reduced to a simple dialectic of familiarity and change—Martin invokes lyric parataxis and prosaic musicality to, respectively, countermand and reinforce vehicles of transformation. And as the book’ s title implies, transformation is just a few cells (and, in writing, a few letters) away from transmogrification. The book is thus organized according to time-lapse techniques rather than narrative epiphanies. For example, the last section, optimistically named “Operatic, the Book Escapes the Book,” is cut, as if unadulterated hope was too lethal a drug, by the ambivalent last line of the book: “Tightrope from which we emerge.” Here, as a few pages before, flights of fancy (“To mutate is to live”) take off from the decks of civilization (“Call it a shoe worn over whole magics”), serve as “Counterband” (the name of another section) to the “com- / pound ” box labeled Afro-pessimism. On the one hand, Good Stock Strange Blood posits “black” against “they,” acknowledging the obstinate objectification of the African Diaspora by colonizing subjects (Black and white). On the other hand, inasmuch as “black” is just another “com- / pound,” an enforced with-ness (i.e., “we”), Martin detaches her narrator from a composite “black”—as well as from a reductive “female”—in order to defer, indefinitely, the dovetailing of culture and biology at the nexus of race and sex. Against this historical positivism, Martin invokes negation: “I am not a boy in anyone’ s body. / / I am not a black in a black body.” Had it not been commodified as the go-to badge of a proud ambivalence, queerness might be a word for what Martin is attempting here. Still, as a placeholder for “what can be accessed only because it cannot be reached,” queerness may have to do.

But “to be” queer and to queer something is, in both cases, to give in to the infinitive. For Martin, being, the infinitive par excellence insofar as it appears as history, must be refigured, transformed into that which flirts with monstrosity (another name for the divine). Thus, the opening metaphor of the book as a “house” with a “foyer” (here, the Prologue) immediately gives way to the book as “a long, thin, wavy tendril” attached to “a small spot at the top of [the narrator’ s] head.” However, the Prologue, cast as an interview, appears inadequate as it is followed by a second “prologue,” or the second part of a divided Prologue: a set of poems titled “To Shed the Traces of Catastrophe…?” Here, “we,” a more capacious term than, if all too presumptuous as, “black,” is posed against “they” in a series of lyric vectors, zigzagging between bafflement (“What is our name?”) and affirmation (“We shut shades”) that will recall, for some readers, certain sections of Zong! or Beloved. The key figure in the opening section, however, is neither “we” nor “they” but “Mother,” an apt “origin” not only because the next section is called “The Baby Book,” but also because the mother is both a figure of reprobation (“‘blackened’ skin, / her ‘tarnished’ ‘whiteness’ ”) and object of asexual fantasy: “to be born of Sarah’ s head, through / sieve, seized wreckage.” The queering of the father figure—here, Zeus—only seems to freeze-frame disaster, for as the above infinitive reminds us, the narrator can only posit a subjunctive voice in opposition to a positive history. For every dream of an “I…made of many arches and windows… / entrances to the many houses of god,” there is “each morning a fireheart grief coming out of sleep.”

It would be too true and too simple to attach causality to the “father,” a word which, like the homily “beloved husband,” finally obfuscates history as the past and present site of trauma. “Father” is only one of several veils that the poem “Obituary” attempts to lift: “I love you like a saw / into barely beating / heart, my body hard / and flat against the coffee table…” Excavating terror and torture from repressed memory, Martin merges this figure with, and poses it against, “my stranger,” “Some Black Unknown,” as she names one section. The stranger, like the father, may only be another figure of the past but, unlike the father, may be the possibility of a future; that “other baby book,” (section three) an alter pre-ego and subconscious “man/woman” that, for example, Martin might have become but now exists only as introjected trauma. Given the actual men that “be” in this world, this figure, one foot in the ego, one in the id, cannot be named as such, can only be hinted at as if “S/he” does (and does not) “exist,” a shadow that haunts these poems and doubles down on both collective and personal trauma. The single slash mark demarcates and yokes together not only gender pronouns but also gender and race. The “logic” of the slash implies that Martin’ s “S/he” is, here, a fucked-over Black / female / / person Janus-faced: the “wrong” and “right” directions. The double slash marks an absolute difference between female and person. The slash, single and double, is given a name, however mythic, at the opening of “Some Black Unknown”:

Once I wrote into being an imagined figure named Perpetuus, whose

name is Latin for “continuous, entire, universal. ” Perpetuus is necessarily

liberated from gender and without attachment to skin or color.

S/he is only reflection.

The companion and predecessor to this piece is “To be an orphan inside of ‘blackness,’” a prose poem which immediately precedes “Obituary.” A takedown of racial microaggressions across cultural and social landscapes (including the publishing and marketing sectors of the poetry business), “To be an orphan” registers Martin’ s distance from the scenes of instruction she nonetheless incessantly rehearses. No mother’ s amniotic ocean to swim back to, s/he can only contemplate the Atlantic, that absence named the Middle Passage by the descendants of those who did not fly—voluntarily and not—off the decks of slaveships. And as Langston Hughes (cf. The Big Sea) discovered when he recrossed the Atlantic to go “back home,” one cannot recross this body of water without dragging along the bodies buried at sea: “Ocean floor filled with dead wings and tar. The slaves blink their slow eyes.” Still too close to be put behind us, those long-dissolved skeletons are perhaps too easily recalled as “history.” In Good Stock Strange Blood, not even the stories of flying Africans can pull the book, an abscessed tooth, out of the book.

§

Clarence Major’ s first compilation of Black colloquial expressions, published in 1970, was simply titled Dictionary of Afro-American Slang. The second, vastly expanded edition, titled Juba to Jive: The Dictionary of African American Slang and published in 1994, demoted the original title to subtitle status. Reversing alphabetical order, the second edition’ s title served as a synecdoche for the backwater blues of the African diaspora. As Ralph Ellison might have said, we go forward by going backwards. Or as Harmony Holiday would have it, relearning what we have forgotten, remembering what we have suppressed, is key to our going-forward survival, to getting through—not over—the trauma of Black life in the West. Of course, to be “Black” is to be a child of the West whether one lives in the United States, France, or Somalia, but Holiday, like Harold Cruse, deploys that trope of modernity—Negro—as often as she uses Black. As the narrator of Ellison’ s novel Invisible Man learns at great cost to his dignity, and as Holiday puts on display in Hollywood Forever, the absurdity of living while Negro/Black in the West must be taken seriously, but not too seriously. Because he was invested in the novel as a genre, and thus in the only “literary” aesthetics available to him at Tuskegee, Ellison took the plunge into “history,” defending and celebrating Euro-American culture in general. He could do so because he understood that American culture—if not American politics—was driven by African and Negro linguistic, musical, and social values and tastes that would soon multiply—or from the perspective of so-called “red-blooded” Americans—metastasize into what we so easily call multiculturalism.

Holiday’ s reaction to this history of mutual, even dialectical acculturation is, as she writes, ambivalent, not only or primarily due to her own mixed-race blood but also due to its effects on African American society at large. This ambivalence can manifest itself as humor, as dread (not fear), and even as ennui. Hollywood Forever showcases all of these reactions. As Holiday observes in her own online notes, Hollywood Foreveris a book to be read while listening to its soundtrack: a Spotify playlist Holiday named “Cantaloupe in the Club ” after witnessing a dapperly dressed brother holding a cantaloupe aloft as he moved around the dance floor of an East St. Louis nightclub. “Cantaloupe in the Club ” is, as I read it, another subsidiary of Holiday’ s ongoing mixtape project Mythscience, which primarily features snippets of speeches, interviews, and dialogue from major, minor, and anonymous players in the Black Power and Black Arts Movements. The textual version of Mythscience in this book is titled “The Afterlife and the Black Didactic: Seven Modes for Hood Science,” and includes meditations on, among other things, the social meanings of the music of Charles Mingus and Sun Ra. Holiday’ s insistence on the relevance and popularity of “jazz” is meant to bracket changes in what constitutes “popular music” even as the motif of “running” as change (of sets, of costumes, etc., the basic shtick of a one-woman show) affirms the inescapability of temporality. In brief, the total voice of Black cultural expression is, and the present tense of the infinitive “to be” (which also points forward) encapsulates what Amiri Baraka, writing about the totality of Black music, once named “the changing same.”

Like Holiday’ s earlier book Negro League Baseball (2011), Hollywood Forever explores the Black public sphere as didactic uplift anchored by a stoic undercommons. The book begins decades after commodified Black musical expression had entered the general public sphere. Holiday reminds us that the domineering appeal of Black music’ s porous and promiscuous genres (e.g., the blues reconfigured as a subset of R&Band country and western) leads to exoticism and backlash: negrophilia and negrophobia as two sides of the same coin. Thus, one of the book’ s motifs is the billboard-cum-flyer scare tactic ubiquitous throughout the pre- and, yes, post-rock ’n’ roll era: “Help Save The Youth of America / DON’ T BUY NEGRO RECORDS.” This once-popular circular is merely the flip side of that other mode of white anxiety regarding the visibility of Black bodies in public forums. The subtitle of Holiday’ s book, taken from a magazine headline, is “Will Hollywood Let Negroes Make Love?” Jesse Owens and Jackie Robinson aside, the fear that Blacks might be nothing more or less than human still hangs over public discourse today (e.g., the analog and digital rhetoric about the bodies of Michael Brown and Michelle Obama). Few will recall—but Holiday is, if nothing else, a committed archivist—that even as late as 1977 the question of Black-Black sexuality being expressed in popular film and on television was grist for the mill, never mind Black-white sexuality (e.g., the controversy surrounding the love scenes between O. J. Simpson and Elizabeth Montgomery in the pre-Lifetime but all-too-Lifetime, made-for-television movie A Killing Affair).

So, from the minstrelsy of Blind Tom to the niggerdom of Kanye West, here we are, in the age of hip-hop ubiquity. Today freedom of expression means the right of Black and white men and women to mock rap music in speech idioms borrowed from hip-hop culture. And as always, a Black body in public remains, if not an exotic nexus of wonder and fear, a curio on display, splayed out on magazine covers, splayed out in the streets, on social media, and so forth. There is nothing new under “the sun [that] kills questions.” And yet the new mythology demands a response, a risk, and so Hollywood Forever tries to outrun the cameras and screenshots by repurposing them. Integrity is, here, the totality of actual history: Martin Luther King Jr.’ s adultery, for example, must be sutured to his assassination, not in causal but human, all too human, terms: “He stepped out onto the balcony for a private cigarette after sex with a woman who wasn’ t his wife (so what) (does that make him) when they shot him.” Ditto for Holiday’ s insistence on remembering that Miles Davis was both pimp and pioneering artist, wifebeater and victim of police brutality (“He’ s gonna fuck his wife tonight when they get home / tender then harder he’ s gonna fuck her up… ”), that Bill Cosby is both a serial rapist and pathbreaking comedian and actor (Holiday reproduces the iconic photograph of Davis and Cosby having a chat at a party). Her kamikaze sorties (because she too is acquainted with ambivalence) are no more attacks on “all” Black men than the recent #MeToo solidaritycirculating on social media reads as misanthropy (despite the predictable blowback of All Assaults Matter).

More broadly than she did in Negro League Baseball, Holiday attempts to jump-start the dreams of cultural generalists such as Baraka and Lorenzo Thomas to recapture African American culture as one sector of a totalizing voice that will never complete itself insofar as it remains open to a future over which it has no control. Holiday envisions this total voice as already always a timeless continuum embodied in prophets like Sun Ra and Alice Coltrane, and the new/old things of Kendrick Lamar. This total voice, which might be called Afrocentric feminism, also embraces non-Western cultural practices and values (e.g., a Honduran doctor who claimed to have cured AIDSthrough allopathic medicinal remedies and culturally based polygamy as a prophylactic against pedophilia and adultery). Writing and dancing are Holiday’ s individual embodiment of this diffuse totality, methods that might serve to access a “hidden language” articulated in movement per se (her Vimeo production in which she reads a selection from the book over collages from Black films and videos is titled “To be running and not in fear”), in the representation of movement via ads, photographs, and movie stills.

How to “show” writing as dancing, dancing as writing? Holiday uses unconventional spacing—sometimes phrases, sometimes words, and even letters—to depict the rhythms of self-interpreting dance, the dance of a jazz-inflected intellect. The stuttering rhythms also manifest themselves in the larger formal patterns—repetition of certain pages and phrases (“Do Not Buy Negro Records”) and sentences that show up several times in different fonts, colors, and cultural contexts. However, the most arresting facet of Hollywood Forever is Holiday’ s deployment of montage and palimpsests. She embraces spectacle as the inevitable consequence of the African Diaspora even as she critically engages the salacious spectacle of Black people in the public eye. For example, in siding with Black women who suffer physical and emotional abuse from Black men, Holiday nonetheless admits that she is “tired of the resin in every great preacher’ s voice, the / perfect sanctimony of manhood is better pimps are better than holy men… . ” Inasmuch as Holiday links the sartorial splendor of both preachers and pimps with the bling of Black entertainers in general, she interprets spectacle as style, as élan, flair, and above all, as the affirmation of dignity and pride long displayed in popular Black magazine titles (Ebony, Jet, Tan, etc.). Fashion and style are also modes of (out)running without fear.

Nonetheless, as Ellison knew, and as Holiday repeats here, Black survival in the West has always depended on accepting ambivalence as a stance, however wobbly, however buffeted about by the clarion calls of certainty (hence her hostility to religion). Holiday’ s ambivalence is mounted in the frame constituted by the opening (“I want a land where the sun kills questions”) and the penultimate sections (“But then where do we bury the questions killed by our benevolent sun”) of the book. This motif might be understood as the recourse to Afrocentric resources hidden behind or as one plane (one page) of the palimpsest that is Black history. And as Negro League Baseball made clear, the American myths we forge from African and European myths already have a long tradition, however buried under the sediment of history. In that sense, Holiday’ s multiple projects are scholarly: historical recovery as essential to our knowledge about the past and, consequently, to our orientation toward the future. Hollywood Forever is a contribution to this science of myth, an untimely reminder of our humanhood.

§

Despite two previous very good books of poetry, Drag (2003) and Amnesiac (2010), Duriel E. Harris is probably best known for her one-woman performanceproject Thingification. A theatrical sojourn from the present to the past (and back again), Thingification deploys call-and-response tropes to deconstruct congealed concepts of race, gender, and sexual orientation, positing in their place a spectrum of intersexual and intertextual positions. Harris demonstrates these possibilities in her chameleon-like transformations into, and through, a historical network of eight characters. In No Dictionary of a Living Tongue Harris revisits some of the themes of her previous books: the intersections and divergences of racial and sexual identity, the self and the body, and the relationship between remembering and forgetting. No doubt part of Harris’ s relative “invisibility” is that her poetics and motifs are quite similar to that of her Black Took Collective compatriot Dawn Lundy Martin, and indeed parts of No Dictionary of a Living Tongue may remind readers of Martin’ s 2015 book, Life in a Box Is a Pretty Life. Both Harris and Martin use inscribed boxes to showcase the relationship between history, the written par excellence, and the enclosed body of a person, of experiences, etc. However, as Thingification suggests, Harris wears her multiple selves on her sleeves, and unlike Martin’ s more insistent sense of self, Harris seems more ambivalent about the possibility of a self even as she insists in the title section of the book that despite “…The thing we are / cut off / /…speech inhabits a body / making and hearing sound / its deciding witness: / skin, a throat unwound.” Of course, if the skin, an external organ, is “a throat unwound,” inner and outer are indissociably linked. Yet, the possibility of an unalienated integration of the body as a coherent self is counterpoised by the very structure of the book and the way that Harris deploys the preposition “from.”